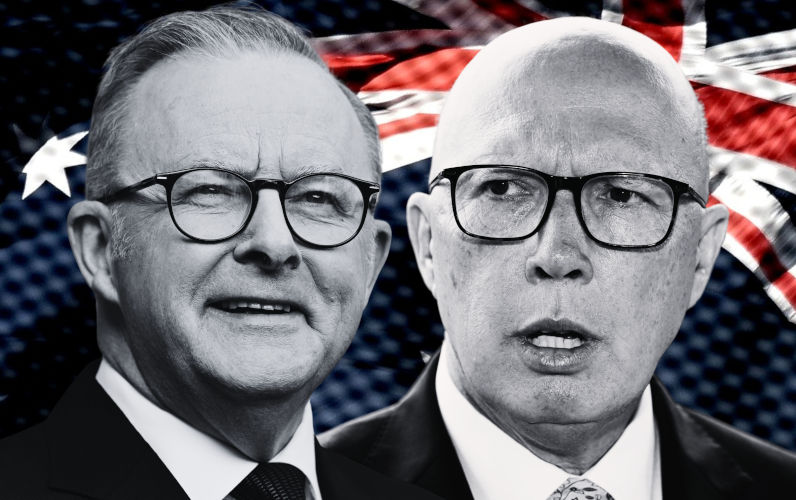

Federal election: A different type of beauty contest

April 15, 2025

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton is fighting this election as if it were what some of my sisters in journalism would call a dick-measuring competition.

On many of the key issues, he invites voters to assume that he is firmer, stronger and tougher. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is, by implication, smaller, weaker and (dare we say it, as Dutton has) more limp-wristed. I have no idea of the size of either’s private parts, but I am cynical enough to know that size is not a synonym for masculinity or courage, and self-advertisement is not, of itself, evidence.

I have often criticised Albanese’s policy timidity and failure to share with voters what exactly he intends to do, and why. And how he thinks that the thick grey soup cooked up by too many committees solves whatever problem lies before him. He has big problems getting any audience, even caucus, excited or inspired. He has no policy genius, no marketing skills, and would be in deep trouble if Dutton were not equally deficient in speech-making skills and charisma.

Those marketing Dutton are seeking to capitalise on widespread perceptions of Albanese’s limited stock of daring, decisiveness and willingness to consult voters, or backbenchers. It’s a legitimate tactic, but not one best achieved by portraying him as a wimp, effete or pusillanimous.

The metaphors Dutton uses are a matter for him, and Albo is, in general terms, fair game. The risk is rather more to Dutton. He has long been marketed as someone who knows what he thinks, and who doesn’t care much, at first instance, what others think. He usually doesn’t mince words. He often goes out of his way to offend various constituencies, such as Aborigines, migrants from Africa, public servants, people from Canberra, unionists, or those in the inner suburbs of state capitals, who are dismissed as “woke". This may be plain speaking and certainly serves to polarise voters and appeal to those who share his distaste (he hopes the majority) for those he is targeting, perhaps by dog whistle.

But the election campaign has not shown a firm and decisive Dutton. Far from it. His status, as such, has declined. Nor has it shown him as a man of courage, firm conviction, or having a firm set of ideas about what to do to change Australia for the better. If what Dutton has been doing so far represents the firm, purposeful and dogged man behind his personality and his character, the ordinary punter will wonder at the macho, masculinist self-descriptions and whether there really is any substance behind him.

Dutton has never worried about being perceived either as a hard man, or as a person who brims with human kindness. He is not given to emotional moments or private grief. He believes he is representative of a great cohort of Australians, including fair dinkum cops, who think that too many people are mollycoddled, are over-dependent on government and given more to complaining than self-reliance. He’s also a better than average example, he thinks, of people who have raised themselves by their own bootstraps, and by keeping his eye out for where a quid can be legitimately made.

The tough, patriotic, unyielding man in sharp contrast with the timid Albanese?

Dutton identifies with “strong”, worthy (and often meaningless) sentiments such as “patriotism”, “toughness”, and “unyielding” firmness. He is the “leader” who will “take Australia’s side”, “stand up” for its interests, and who will “do whatever it takes” to get maximum benefit for the nation he loves. Since he is closer ideologically to Donald Trump and can appeal to the MAGA leader’s base values, feelings and cynicism about government, he is more likely to be able to attract Trump’s sympathies and favours. Trump, after all, actively despises almost all of the values and ideals for which Albanese has ever stood. Unlike Trump, Albo is no radical. He respects political and moral conventions, and the law. He does not abuse judges or ascribe any adverse or perverse court outcomes to malevolent bias from judges who started on the other side of politics.

On this, as other things, Dutton is closer to Trump than Albanese. But unlike Trump, Dutton is no radical or revolutionary, out to turn the system on its head. He has no bold agenda to change the constitution, or to reform fundamental processes of government. Presumably he entered politics to effect some change, but one cannot see any drive in a particular direction. He is guided more by tedious prejudices and predispositions than by any body of philosophy.

There are some changes he would like, for example to the constitutional separation of powers (of which he has a Jo Bjelke-Petersen type of understanding), but he is realist enough to know they would never succeed at a referendum. (But his complaint, of judges intervening in migration decisions, is deeply felt and a recurring theme over the years, raised again this year in terms of thinking it might be a good subject for a referendum. Bees-in-bonnet matters are always useful guides to the character of politicians. It has a history in the Old Testament Book of Proverbs, chapter 26: “As a dog returns to its vomit, so a fool repeats his folly.”)

Australian voters have no means of knowing how Dutton would be different in his approach to Trump. What arguments he would press have not been mentioned. Nor has he made any public case in the least bit different from what Albo, his ministers and his representatives, have said, on why Australia is a special case, in a particular relationship with the US that deserves more credit than it is getting. That may partly reflect conventions about how opposition politicians make politics about different international policies, but that has always been, in the Australian system, a very flexible approach. Both John Howard and Scott Morrison, for example, openly campaigned for Trump at different times.

There was never a time when there was such an opportunity to have a wide-ranging debate on the US relationship. It is not one initiated by disloyal Australians. It has been the Americans who have changed everything, and with the world as much as Australia. The style has been “nothing personal – we know you are fine chaps. But from now on everything must change, and you will not be exempted”. The conversation which is necessary is not merely one for whichever leader emerges to conduct in privacy, but one in which every Australian is entitled to their two-bob’s worth. Perhaps there will be little practical difference in the alliance relationship at the end of the day, but it is very difficult to see how that new relationship will not be affected by new commercial relationships, by America’s open abandonment of the rule-book, and by the anger and hatred caused by the breaches with Canada, the European Union and Ukraine. Given Trump’s erraticism, it is not hard to imagine that the different personalities of Albanese and Dutton may produce different outcomes at the margins. It is not obvious that Dutton would do better. What we do not know — and what we deserve to know — is what either leader will bring to the discussion, beyond their personalities. Frankly, neither is winning. It is unconscionable that voters are not behind whatever agendas are at play.

Dutton should be leading a debate on our future relationship with our main ally. And about the future of AUKUS.

Voters are not as preoccupied as they should be with Australia’s changing place in the world. In much of the argument that we need a stronger, more potent personality than Albanese to be in charge is the idea that Dutton would somehow be different. And better. But he has done very little to show why, or how. A mere history of a belligerent and divisive style is not, by itself, evidence of a stronger personality. Nor does it necessarily show a better capacity, when a problem arises, to examine the facts, to look at the constraints, and to make the most appropriate decisions. Dutton’s experience in government shows him to be experienced with the processes of government, with the capacity to exert his authority over his ministry. But his claim of a history of better decision-making, or better decisions, is quite contestable.

Moreover, Dutton has not pretended otherwise. He has said, often enough, that Albo is useless and hopeless and weak. He has derided his authority and his indecision. With very loyal assistance from much of the mainstream media, particularly The Australian, Dutton has succeeded in inventing crises, allegedly demanding some decisive action by the prime minister. Sometimes this has been with a confected emergency in immigration, or with some development in antisemitism, said to require fresh legislation and further restrictions on freedom of assembly. The ALP is now at least as illiberal as the Coalition. All too often such campaigns have made the government panic, as also the more susceptible state governments, particularly in NSW. But they have not demonstrated that Dutton is more in charge of events or provides alternative leadership that puts the government to shame.

More generally, Dutton asserts that he is better able to make the right decisions and have them work. But he has been very slow to show what those decisions would be, or why they are steadier and more statesmanlike. Nor has he usually approached the issues calmly from principle or precedent. He seems more interested in creating the impression he is doing the right thing. Instead, his attacks have come from overblown slogans based on the perfection of previous Morrison-era policy, and exaggeration of the consequences of failing to prop up policy that has plainly not been working. As often as not, the practical response from government has not been policy courage or thoughtful review, but panic and attempts to lock the issue down. (Usually by locking up more people).

Dutton’s policies and his style of leading his team are not election issues. He has a clear point of differentiation with his nuclear power proposals, but these have been considerably de-emphasised in party advertising. Likewise with the remnants of the policy of reducing the numbers of public servants, particularly those based in Canberra. There is nothing remarkable about this: claiming that the public service is overstaffed and rife with waste is a standard Coalition campaign argument, as is the claim that the billions liberated by sackings will fund all policy promises. There are policies of restricting immigration, but these do not represent much change in general Dutton-style. In any event, Labor, with characteristic courage, has avoided any head-on collision with Dutton’s immigration policies.

He is a law-and-order man who would like to see more toughness and punishment, including tougher jail sentences for malefactors. He thinks ministers are too constrained by administrative law, procedures and requirements about natural justice, human rights, and due process. With the help of weak and woke judges and quasi-judges in administrative tribunals, bad people, or people we can do without are getting away with murder, he believes.

The shortage of developed policy is not necessarily a big minus among ordinary voters. Most expect a return to the broad policies of the Morrison Government and its style of operating. That ought to strike horror among those who saw Robodebt, the scale of party-partisan rorting and the lack of transparency and accountability in that government, with Dutton as much responsible as any other senior ministers. But the incompetence, maladministration and plain corruption is not to be taken as what voters want, even if there is a serious risk that it is what they will get. Rather they expect a government in which the Coalition will preside over the economy, responding to events without much in the way of an agenda. In many respects, though, they will deny this absolutely, they mean following the broad guidance of experienced and bland public servants with the attention to detail Coalition ministers and minders tend to lack. The task these days, after all, is more about outputs for favoured constituencies than outcomes for the citizens who need it most. That, alas, under Albanese as much as Morrison, is the new reason for winning elections.

Republished from The Canberra Times, 11 April, 2025