How Australian education was captured by arms dealers

April 10, 2025

Australian universities, technical institutes and schools are becoming militarised. The power of defence industry money combined with government policy and public underfunding of education have created an avalanche of defence funding and profound influence over our education system and the people who emerge from it.

This is happening without any serious community engagement, public debate or even Parliamentary consideration. The stated purposes are to increase sovereign security and build economic resilience and prosperity. The actual aims relate more to perceived advantages for the (mostly foreign-owned) arms industry, funds for a cash-starved education sector and federal and state governments looking for a spur to jobs and growth. The effects are economic distortion, geopolitical risk and societal and ethical decline. There are major potential opportunity costs for democracy, environmental security, public education, global public safety and open intellectual inquiry.

Corporatisation of universities has paved the way for militarisation. Universities are suffering withdrawal anxiety associated with their tenuous dependence on overseas students, dependence that stemmed from the reduction in government support. Precarious academics, ever more reliant on grant funding for survival, will go where the money is. Defence research funding from US military corporations is providing funding for research and teaching. From 2007 to 2022, the year after the AUKUS agreement announcement, the US Defence funding to Australian universities has jumped from $1.7 million to $60 million annually.

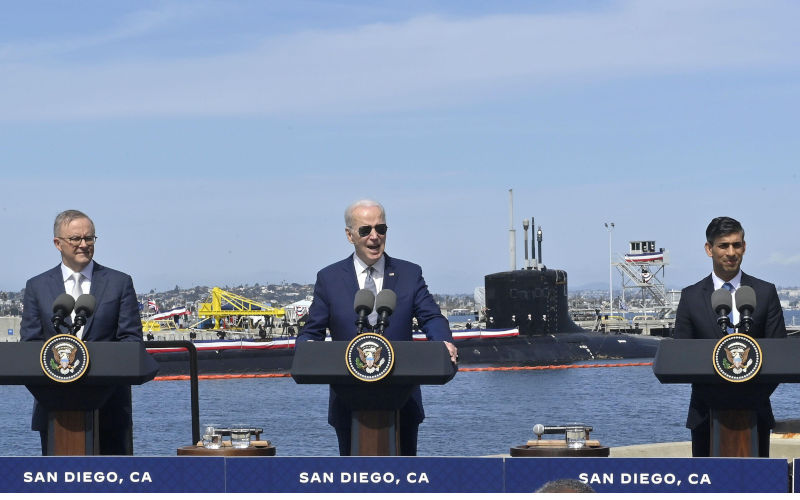

The AUKUS agreement has turbo-charged the trend. A recent Times Higher Education Summit Outcomes Report highlights the role of universities in aiding government with “strategic messaging and building social licence for AUKUS”. The advent of nuclear-powered submarines depends on a workforce with the relevant skills, and universities are keen to provide skills training. Group of Eight chief executive Vicki Thomson claims, “G08 universities have significant defence capability” and were therefore able to “play a major role in the development of the nuclear submarine capability”. (Group of Eight Australia 2021). Universities are increasingly seen as central to national military capacity.

The links between the military, academia, defence industry and government are now so intertwined that Troth (2023) talks of the emergent Military Industrial Academic Complex-MIAC. Yet there has been no open debate about the claimed advantages and evident dangers in this development.

Defence policy has been transformed with the Australian Government’s Defence Science Technology Strategy 2030 calling for “a national S&T [science and technology] enterprise”, comprising publicly funded research agencies, universities, large defence primes, SMEs, and entrepreneurs (Australian Government 2020c, 2) . This is mirrored in all states which are highlighting their defence presence, defence industry, universities and collaborations. The Factory of the Future involving BAE Systems Maritime, Flinders University and the SA Government is but one example which claims to “support the federal government’s desire to accelerate the growth of high value manufacturing industry and jobs and advance its ambition for Australia to become one of the world’s top 10 global defence exporters”.

The latest research undertaken by the Medical Association for Prevention of War has found that major weapons companies are seeking to build positive brand recognition among Australian primary and secondary students. Its findings identified 35 STEM programs associated with global weapons corporations in 2022, up from 27 in 2021. STEM programs sponsored by these companies often target girls and young women, and young people in regional Australia. Programs and materials are branded with weapons company logos using children’s toys and characters to create positive associations in children as young as four years old.

There’s a growing trend of weapons companies developing a STEM curriculum that promotes skills and interest in military technology, raising concerns about commercial interests shaping educational policy. This draws students into defence industry careers, potentially at the expense of other STEM fields, especially sustainable development and climate change mitigation and adaptation. The AEU (Australian Education Union) has also expressed concern about the normalisation of militarism and downplaying of nuclear risks in schools, particularly regarding the health and environmental risks associated with nuclear technology and warfare.

The effects of the burgeoning MIAC are profound. If “successfully” implemented, it implies an economy increasingly dependent on preparations for warfare. Strategically, it fuels the very arms build-up anxieties that are used to justify its existence. The funding from the US Defence Department and US armaments giants, such as Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, locks Australia further into an interoperability trap with the US at a time when that nation is pursuing erratic foreign and defence policies at odds with democratic values and international law. Australian arms exports are focusing on asymmetric technologies including autonomous weapons that can use AI technologies to identify and kill human targets.

The corporate university is also much less open to criticism than universities that were run by a community of scholars. The extent of arms companies’ support for universities means that criticism is not welcome. In the past, university academics have been strong voices for peace and have been a strong voice in response to developments such as the emerging MIAC. US arms manufacturing money casts a dark shadow over the likelihood of such critiques being welcome. This is an erosion of the ethical and social licence of our universities. The repression of student protests over Israel’s continuing genocide in Palestine and the smearing by universities of any criticism of Israel as antisemitic are early and deeply disturbing examples.

As a nation, we urgently need to ask: is this the way we want to go? To date, both major parties quietly ushered us down this dangerous path without a murmur. Good for the university executives, good for federal and state governments, perhaps good for the economy, but good for Australia?

In South Australia, a coalition of groups have organised a public forum to inform citizens and ask what it means for our education system to be captured by arms dealers. Join us in this discussion on Wednesday, 28 May from 6-7.30pm at the Pilgrim Church, 12 Flinders Street, Adelaide.

Paul Laris, Fran Baum, Jon Jureidini, Freya Higgins Desbiolles (all on behalf of Teachers for Palestine SA, Academics For Palestine SA and Students for Palestine SA, and supported by Australian Friends of Palestine Association)