Trump: a ridiculous ego and incredibly ignorant

April 17, 2025

The analysis underpinning Donald Trump’s tariff policy is fatally flawed. Thus, it will fail to achieve its objective of restoring the living standards of his MAGA supporters.

Since Trump announced increases in tariffs on imports, most of the media commentary has been about the impact on different countries’ economies, and Australia’s in particular.

This article will, however, consider (i) the nature of the problem that Trump is trying to deal with, and (ii) how effective his proposed solutions will be. The conclusion is that fundamentally Trump has not got a clue about what he is dealing with and, worse still, no-one in his administration is correcting him.

The US problem

The appeal of Trump’s MAGA movement has been concentrated among male workers, especially whites. According to research by Noble Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz, “the typical American man makes less than he did 45 years ago (after adjusting for inflation)”. In other words, these workers are not only worse off than they used to be, they are worse off than their grandfathers, which is a complete denial of the “American Dream”.

Understandably, this large group of voters can be readily convinced they are the victims of globalisation. Trump’s support base is looking for someone else to blame for their predicament. Who better to blame than foreigners, and particularly the Chinese?

Blaming globalisation for the suppression of American living standards is, however, based on fundamentally flawed analysis.

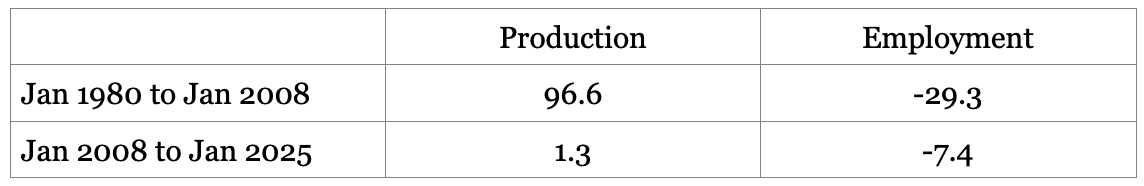

If Chinese competition was driving the loss of American manufacturing jobs, then logically that same competition would have driven a decline in US production. On the other hand, the reality is that American production continued to increase until around the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, nearly doubling over the 28-year period since 1980. Further, even since 2008, American manufacturing production has not fallen, but rather has stabilised (see Table 1), while the decline in American wages dates back to the early 1980s.

The real problem is that manufacturing jobs fell dramatically by nearly 30% between 1980 and 2008 and continued to decline more moderately since then (see Table 1).

Table 1 The increase in US manufacturing production and employment %

But if American manufacturing production continues to grow while employment fell, that effectively means productivity increased. This increase was driven by technological change, and automation in particular, so foreigners could not have taken American jobs as US production is rising, not falling.

The real problem in America is that those productivity gains were very unevenly distributed. According to official (BLS) data, median hourly compensation (adjusted for inflation) grew by only 9% between 1973 and 2014, while productivity growth was 72%. Further, most of the wage growth in the US was concentrated at the top of the distribution and most workers missed out.

But nothing is inevitable about this stagnation in US wages and the associated increase in inequality.

As last year’s Nobel Prize winners, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, have shown in their recent book, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, technology is malleable. Thus how new technologies will use and economise on different factors of production, and who wins and loses, is a matter of choice.

As Acemoglu and Johnson put it: “Technology does not have a preordained direction, and nothing is inevitable. Technology has increased inequality largely because of the choices that companies and other powerful actors have made.

“Different choices [about the direction of digital technologies, for example] will likely translate into gains and losses for different segments of the population.”

Thus, the increase in inequality witnessed in the US since the early 1980s has been driven by technological choices in favour of automation that led to the hollowing out of middle-level jobs. In addition, further choices effectively ignored the possibilities for retraining and the creation of new jobs that would have helped maintain living standards and income equality.

As an example, of how different choices can make a difference even when the technology is similar, Acemoglu and Johnson discuss the way German and Japanese carmakers responded to the automation of their production lines by also creating new jobs that lifted productivity and retrained the staff to fill them, while the US concentrated on cutting costs. The net result was that employment rose in the German and Japanese auto industries, but fell in the US between 2000 and 2018. Productivity increased faster in German and Japanese auto production as did their profits.

In addition, a further problem in the US is that in more recent years, the loss of middle-level jobs has also led to a loss of consumer and, thus, aggregate demand. This is the principal reason for the economic stagnation, while productivity growth has been the lowest since the 1940s, notwithstanding the spread of digital technologies.

So, if Trump was fair dinkum about trying to restore the living standards of American workers, and thus Make America Great Again, he would sack Elon Musk and reconsider how technological change is introduced in America.

Why Trump’s policies won’t work

But not only has Trump completely failed to understand the causes of the problem he is trying to deal with — the reason why US real wages have fallen so much — he is also completely wrong about why America has a trade deficit.

According to Trump, the US trade deficit has been caused by the “unfair” policies of other countries, and these problem can be overcome if they pay high tariffs to enter the American market.

Presumably, that is why Trump came up with the absurd idea that the tariffs imposed on each country should be determined by the size of the US trade deficit with that country.

What Trump, and his advisers, have totally ignored is that a country’s current account balance is always equal to the difference between that country’s production and its aggregate domestic demand (representing the sum of personal consumption, private investment, and government expenditures on goods and services). The trade deficit dominates the US current account balance, so if the US has an overall trade deficit, it must be because its domestic demand is higher than its GDP.

Tariff increases or a lower exchange rate could help remove that deficit, but only if there is spare capacity and its GDP can be quickly increased to substitute for foreign-made goods. However, the US is operating at very close to full capacity, with a low rate of unemployment and high employment participation, so realistically its production capacity cannot be readily increased.

Instead, the only sure way to reduce the US trade deficit is not by increasing tariffs, but rather by reducing domestic demand by increasing US savings. And the obvious place to start would be to reduce the government budget deficits which are running at an extraordinarily high 8% of GDP.

But there is no way that Trump is planning to reduce the US budget deficit. Instead, he is planning to deliver an income tax cut — most probably biased in favour of the rich. According to Trump, his income tax cut will be financed by his extra tariff revenue, but realistically the tariffs will only raise a lot of revenue if they fail to achieve their purpose of reducing US imports by very much and, instead, add to inflation.

Furthermore, given the continuing high US budget deficits, even if the extraordinarily high tariffs on China succeeded in reducing the US demand for Chinese goods, the likelihood is that the US would then import more from other countries. In fact, this is what happened when Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese imports during his previous term.

In sum, the conclusion is that thanks to Trump, the US budget deficit will get worse, and the trade deficit will be even bigger, while inflation will accelerate. The worst possible outcome.