A fistful of dollars: The dumbing down of Australian election campaigns

May 3, 2025

We are mugs. This seems to be the first assumption behind most Australian election campaigns.

We are selfish. This is the second assumption. These perspectives hinge upon flawed assumptions of human nature and limited world-views. There are other viewpoints to consider.

The campaign wasteland

We have witnessed the orchestrated and predictable vacuity of yet another election campaign. We have seen political leaders kissing babies, cooking “democracy sausages”, standing at petrol pumps, being accompanied by embedded media packs, and wearing Hi-Vis jackets. Here we go again. Both major parties seemed to think that constant exposure to their slogans “Get Australia back on track” and “Building Australia’s future” was enough to secure our votes. Or scare tactics like “Can you afford the Greens?” Or vague instructions like “Put the LNP last”. Visual exposure with little or no policy content.

We are not the US where the focus in on two main presidential candidates of Republican and Democrat orientation. What about the candidates standing in all the other seats? Do we ever see or hear from any of them? Where is the information about the wider field of candidates? You must look hard to find them.

We are all mugs. Political parties think that if they make their election campaigns simple and basic, then cynical electors will vote for them. Dumb it down, provide no real policies, and, of course, don’t provide any costings for all the promises, or do so when it is too late to inform any undecideds. The Coalition will release its costings two days before the election, while the Greens will conduct their campaign launch the day before – as if this means anything.

What about policies beneath the slogans? Where are they? Are there any policies, serious goals, or are all these just promises and thought bubbles? Being constantly texted by various politicians and parties also merely angers and disengages an already disillusioned public. Does anyone conduct any serious research into what engages the voting public? And what turns us off?

We are all selfish. “WIFM” is the second assumption – “what’s in it for me?” “Save 25c per litre. Vote Liberal”. This seems to be the only mantra driving campaigns every time there is an election. Pure unenlightened self-interest is the assumption behind these campaigns.

Here’s a fistful of dollars for you – aren’t we clever? The spaghetti Westerns Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965) highlighted the same basic imperative – to get what you can for yourself. The assumption of human nature behind most election campaigns is “give them money to buy their votes”.

The tone and content of most campaigns is to appeal to voter fear and voter greed, the two basic human emotions. Are we so stupid and so selfish as to be motivated purely by this? What else could candidates and political parties do? What else drives human nature?

Beyond self interest

Here’s a novel thought – why don’t those who stand for public office think of the greater good, the common good when they present themselves as candidates? What a great idea to think about a more prosperous, happier, and healthier society for us all.

Wouldn’t it be a novel concept to encourage people to think beyond their own self-interest? How about we think of others when we cast our vote? To think of the bigger picture, even to have bold “moon shots”. After all, younger voters do worry about healthcare for their grandparents; older citizens are dismayed that young people can’t afford rent or to feed their families. Older men do worry about the toxic masculinity to which young men are exposed, and older women worry about whether their daughters will be safe when they go out at night.

It all hinges on the assumptions of human nature held by political parties and their campaign directors.

Assumptions of human nature

Attitudes about people, in general, form assumptions of human nature. As long ago as 5BCE, Socrates held the view that “our youth today love luxury. They have bad manners, contempt for authority, disrespect for older people. Children nowadays are tyrants. They contradict their parents, gobble their food, and tyrannise their teachers". Critical evaluation and assumptions of others are not new.

In leadership theory, there has been consideration of assumptions of human nature which also reflect different world-views. For example, “Theory X and Theory Y” was the model of leadership created in the 1960s by Douglas McGregor from MIT Sloan School of Management.

“Theory X” is based on negative assumptions regarding employees. This management style assumes that workers have little ambition, avoid responsibility, and are individually goal-oriented. It showcased an instrumental world-view. “Theory X” managers believe their employees are less intelligent, lazier, and work solely for income. Management tends to believe that employee effort is driven by their own self-interest.

“Theory Y” is based on more positive assumptions regarding employees. “Theory Y” managers assume employees are internally motivated, enjoy their jobs, and work to better themselves without a direct reward in return. It showcased a contractional even a “covenantal” world-view. These managers view their employees as valuable assets, and valued people.

McGregor also found that “Theory Y” managers encourage better long term-performance from staff and sustainable organisational results, leading to the importance of a “psychological contract” between managers and employees. There’s a novel idea – a psychological contract between elected officials and voters, not just a transactional buying of votes.

Politicians might do well to consider that there are different assumptions of human nature:

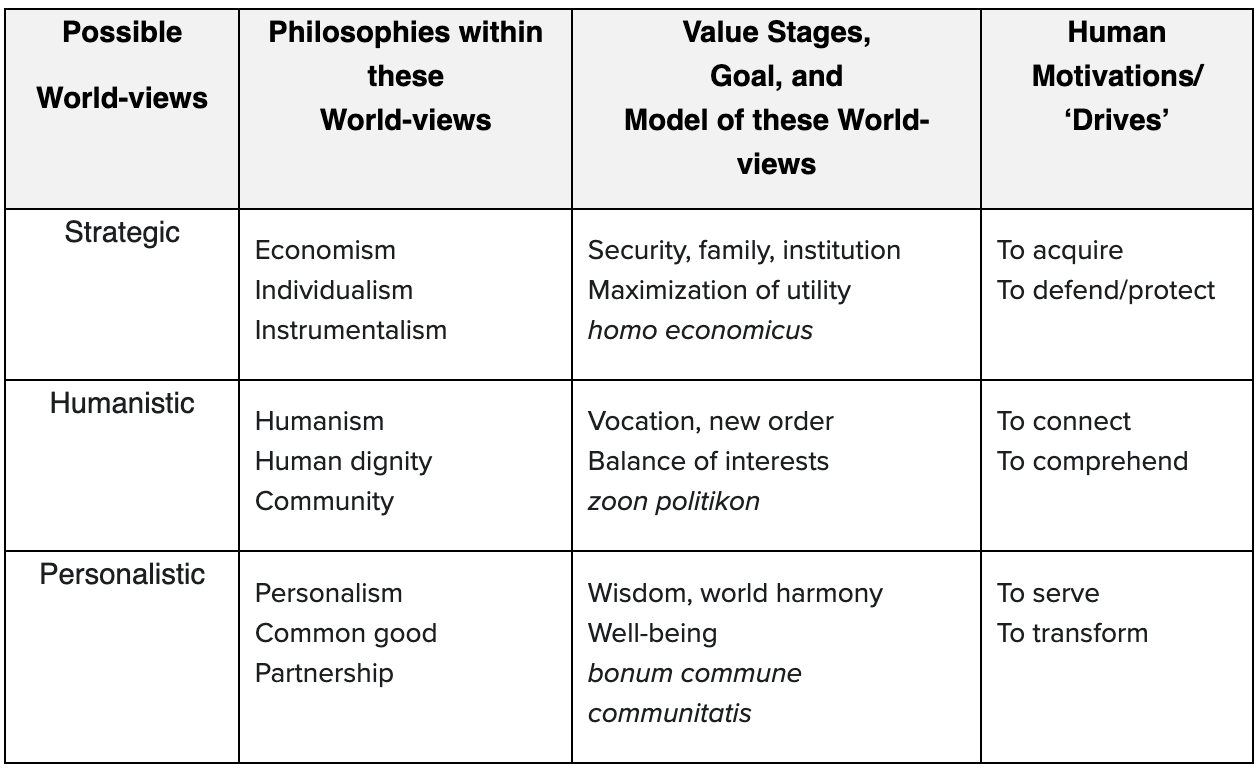

The strategic world-view espouses that people are mainly assets and resources to be accessed; the humanistic world-view recognises the dignity of human beings; while a personalistic world-view also endorses the dignity of human beings, but emphasises that we only become persons when we work towards the common good.

An individual human being is a “lower self”, striving for itself; while a person is a “higher self”, striving for self and others. Persons are unique, free, self-determining, and connected to others. Politicians could do well to think the best of human nature and remember that.

Maybe politicians and their campaign directors could recognise that we, as voters, are not all driven by the motivation to get, to defend, and to be selfish. Some of us want to understand the world in which we live, to better connect and to build safer, stronger communities which look out for others. Some of us might even want to serve others, and to transform our society to create wealth and well-being for all.

Conclusion

There is another pathway to political campaigning than appealing to unenlightened self-interest based upon the selfish assumption of homo economicus. This alternative pathway is glimpsed in the ABC “Your Say” platform and implied in the site, “Build Your Ballot” where people want bolder, bigger ideas and a vision with realistic hope for the future, not just a fistful of dollars for themselves.

Without a vision, the people indeed do perish. Our political parties and their leaders need to challenge their flawed assumptions of human nature – we are not all dumb and selfish.