A campaign with only one contender

May 2, 2025

Not since the conservative nostalgia of diminutive liberal Prime Minister Billy McMahon, whose timidity, wooden delivery and stolid conservatism was no match for the hope, energy, and optimism of Labor leader Gough Whitlam, has a Liberal election campaign been so poorly developed, so ineptly presented, and so badly run.

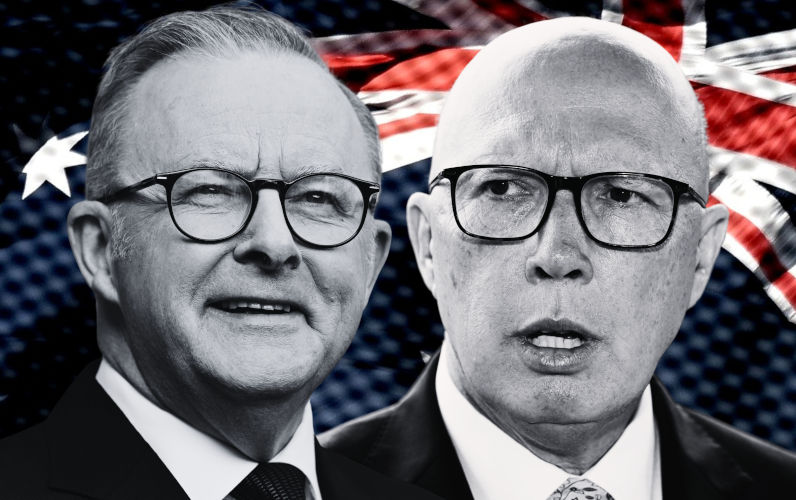

Was it really just a few months ago that political pundits were writing off the prospect of a second-term majority Albanese Government? Although the polls consistently showed barely more than 1% difference between Labor and the Coalition in two-party preferred terms, there was no shortage of commentators ready to consign Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to the ignominy of a one-term government.

Late last year, Albanese shot back at reporters pursuing the latest iteration of this familiar refrain, reminding them that he had been underestimated his whole political life. “I have been underestimated my whole political life and I’m focused on making a difference in cost of living… making a difference for Australians,” he said. Peter Dutton is hardly alone in ignoring Albanese’s generous self-assessment, although unlike those he now dismisses as “hate media”, Dutton did so at his political peril.

Even as election victory appears likely, there remains a notable failure to recognise in Albanese the calm, measured, political leader whose methodical approach to policy development and focus on everyday cost of living essentials — health, education, housing, childcare, improving wages and conditions especially for low-paid workers — might be exactly what is needed at this time. The much-vaunted significance of Donald Trump in this election lies more in what it tells us about Albanese and Dutton through their differing responses to Trump’s aggressive isolationism, reinforcing existing political traits – to Dutton’s particular disadvantage.

Dutton’s early embrace of Trump-ist DOGE efficiency measures, his appointment of Jacinta Price to drive such measures, his promise to slash 41,000 public service Canberra jobs and reverse the Albanese Government’s advances in renewable energy reflected a significant political misjudgment in mistaking the American political system for our own and misreading its electoral implications. Faced with the turbulence of Trump, the chaos of on-again off-again tariffs and mass public service “efficiency” sackings, voters had already turned towards Albanese’s political approach and promise of stability and consistency, which some commentators saw only as “insipid”, “uninspiring” and “dull”.

After three years in government, Albanese is a different political adversary. It’s a truism to say that an election campaign is a marathon, because it is. He has prepared relentlessly, physically and politically, done the policy work and, it seems obvious, some impressive media training as well. There have been minimal stumbles, greater clarity, and a remarkably disciplined presentation of a detailed policy program, including fronting the National Press Club several times which Dutton refused to do even during the campaign.

The contrast between the two campaigns could not be more marked.

Not since the conservative nostalgia of diminutive Liberal Prime Minister Billy McMahon, whose timidity, wooden delivery, and stolid conservatism was no match for the hope, energy, and optimism of Labor leader Gough Whitlam, has a Liberal election campaign been so poorly developed, so ineptly presented and so badly run. This has been a campaign with only one real contender. At the heart of the Liberal Party’s shambolic campaign mash-up lies the one glaring problem from which all others inevitably followed – there were no policies.

It is almost inexplicable that the Coalition, even with a three-year lead-in time — this was no early snap election — could be so unprepared for a campaign, focused as it must be on policy alternatives and political possibilities for the future. And yet here we are. The Coalition is staring down polls that show a dramatic shift away from its lead in early January, to a 47-53 defeat in the latest figures, just four months later.

So, what went wrong? After just the first week, I wrote that although it was too early to say that the wheels had come off Dutton’s campaign, it was looking very shaky. By the end of the following week, the wheels were well and truly off. The image of Dutton’s bogged campaign bus is the lasting metaphor for a campaign dogged by inconsistency, contradictory positions and rapid policy drops, surprising even Dutton’s inner circle in a vain effort to fill the obvious policy vacuum. The Liberal’s work from home policy is the best — or is it worst? — example.

Announced apparently without internal consultation by Jane Hume, no-one had thought to consider how this might affect women in particular, and across households more broadly, through the added cost of fuel for commuting and the lack of flexibility for those with children. It barely had time to settle in the public imagination before Dutton announced a major backflip and the policy was gone. The nuclear policy, another of Dutton’s “captain picks”, meanwhile, simply disappeared from view, rating just one mention in the budget reply speech and with Dutton refusing to visit any of the nominated nuclear sites.

Opposition is a lonely political purgatory, a difficult time for politicians to sustain enthusiasm and remain united. However, it can also be an opportunity for renewal, for policy development and party revival, which the Liberal Party under Dutton has failed to take. Dutton’s own backbench has been restless over the lack of policy development and his tendency to announce policy as a “captain’s pick”, on the run, with neither detail nor substance and leaving his backbench team in the dark.

Take the “ nuclear fiction” of seven promised “small modular nuclear reactors”, the Coalition’s putative energy fix based on technology that doesn’t exist: it would take 20 years to build even if it did, and with an eye-watering price tag for the taxpayer of $600 billion, which the Coalition claims is $330 billion. Touted by Dutton as the clean energy fix to bring energy prices down in 30 years time, perhaps, he also promised to compulsorily acquire land to build the reactors if needed “even if locals oppose it”, and to ignore community concerns, “in the national interest”. The groans of Coalition MPs watching their re-election prospects plummet could be heard across the country. What a political horror story. The nuclear fantasy fell just as hard and fast as it had emerged.

Dutton was jettisoning policies faster than he could make them up. It meant policy announcements appeared arbitrary and capricious. It was impossible to take policy promises seriously from that point on, knowing they could be overturned or forgotten at any time.

The failure of the Liberal Party to do the hard work of rebuilding its brand, attracting a broader voter base through policy renewal from Opposition has been the main cause for the Coalition’s slump. Put under the spotlight of an intense campaign with a rapid media cycle, the Coalition campaign never got off the ground.

It comes as no surprise that, as the campaign comes to a welcome close (the final train-wreck weeks have been almost painful to watch), the political persona of Dutton himself — his divisive, belligerent attitude to government and, more concerningly, to the exercise of power — has become a drag on the Coalition vote. With the final polls showing a decisive shift to Labor and Albanese increasingly likely to retain, and even improve on, majority government, Liberal insiders are already stalking Dutton’s leadership, honing in on his campaign mismanagement. Liberal Party strategists on 1 May anonymously decried the absence of policy heft, noting that in three years the leadership team had presented little more than an aspirational booklet without the detailed policy work behind it.

Bill Shorten, during his weekly tête-à-tête with Christopher Pyne on the ABC’s 730 program, repeatedly described the Liberal Party’s campaign as “lazy”, reflecting the lack of policy development and failure to prepare for office from Opposition. Dutton and his key advisers clearly thought governments lose elections, Oppositions don’t need to do much if a government is on the nose. And, in that, Dutton sadly misjudged the meaning of his “success” in manufacturing opposition to the Voice referendum, apparently expecting that voters would ride a wave of anti-Labor sentiment generated by the failure of the Voice and carry them into government. It was never going to be that easy.