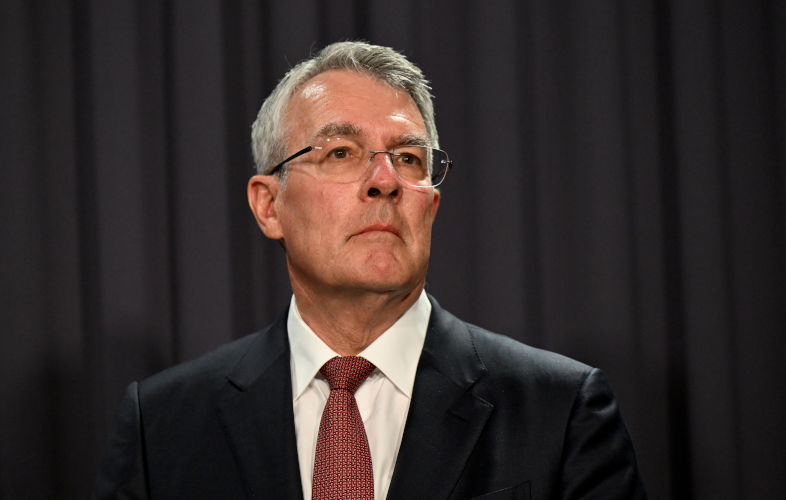

Dreyfus leaves little legacy

May 10, 2025

In his term as attorney-general, Mark Dreyfus failed to address many big issues.

Dreyfus’ legacy as attorney-general is, at best, very modest. In fact, come to think of it, he was perfectly suited to the style of the Albanese Government. Incremental change and a refusal, post the Voice referendum loss, to embark on any of what the great former Labor prime minister Paul Keating called “big picture” initiatives.

Other than creating the new Administrative Review Tribunal to replace the deeply politicised AAT — an easy piece of work because many members of the latter transitioned into the ART — Dreyfus tinkered with other matters requiring attention.

It remains a fact that access to justice is as problematic as ever, and legal aid budgets across the nation are stretched thin. On the latter, consider that Dreyfus announced in last year’s budget he was “providing an urgent injection of $44.1 million in 2024-25 to provide an immediate funding boost to the legal assistance sector to ensure that more Australians have access to justice and equality before the law”.

Big deal. Here’s the reality. In Tasmania, where this writer does some work, the legal aid body has had to cut back on representation for some of the most disadvantaged members of the community because the cupboard is nearly bare. Legal Aid Tasmania’s director Kristen Wyloie told the ABC before Christmas last year that the cuts meant “we will not be able to represent or provide representation for all children which inevitably does place some children at risk”.

A survey of private sector lawyers who provide legal aid, published by the legal peak body, the Law Council of Australia, in January this year, found that “responses paint a picture of legal aid rates that have stagnated for more than a decade and are now around three times less than what they can earn privately. In addition, the complexity of cases, level of support required by the client, and time required from practitioners are all on the rise".

This, at a time when governments across the nation are pursuing cruel and counterproductive policies of locking up more children and increasing sentences for some crimes.

Speaking of which, why hasn’t Dreyfus taken a stand against governments like those of Queensland and the Northern Territory who are clearly breaching Australia’s international human rights obligations such as the ICCPR and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, as they jail vulnerable children in record numbers?

In May 2022, just prior to Labor’s election to government, Dreyfus railed against the Coalition’s attacks on the rule of law, its political prosecution of ACT lawyer Bernard Collaery (who blew the whistle on Australia’s illegal bugging of the Timor-Leste Government’s cabinet room in 2004), and the constant attempts by the Coalition to undermine the Human Rights Commission.

Dreyfus did drop the prosecution of Collaery, but he left two other whistle-blowers to face the courts. One, David McBride, is now in jail after pleading guilty to charges relating to his providing documents to the ABC about war crimes in Afghanistan, allegedly committed by Australian soldiers. The other is Richard Boyle, a former Australian Tax Office employee, who is still in the middle of legal proceedings. Boyle is a whistle-blower who revealed unethical debt collection practices by the ATO. In both cases, Dreyfus could have intervened — a rare step, but one that is available — to prevent these cases continuing.

And when it comes to rule of law, Dreyfus is no better than most politicians. They talk the big game, but at the end of the day it’s mainly lip service. He has not repealed any of the draconian anti-terror laws, nor has he made it clear that dual nationals who return to Australia after service in the Israel Defence Force in Gaza could be investigated for war crimes. He should have done so, given the clear evidence of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide that the IDF is inflicting on Palestinians. To be clear, it is not asserted any Australian has committed such crimes.

But it is in the area of human rights protection that Dreyfus has been most disappointing. If he was serious about the rule of law, he would ensure that a human rights act was legislated for by now.

The sadly now departed great English judge Tom Bingham, in his famous 2008 exposition of what the rule of law means, said a key aspect is that “the law must afford adequate protection of fundamental human rights”. And more than 30 years ago, Bingham chided the government for not incorporating human rights obligations into domestic law, arguing it made it difficult for courts to protect human rights.

Bingham could have been talking about Australia where the rule of law is rhetoric, but not much more in many ways, including, and mainly, because of the failure of governments to pass a human rights law at the national level.

Dreyfus had the opportunity to ensure he was remembered as the attorney-general who ensured Australian democracy was enhanced substantially through human rights protections. He didn’t, and that is shameful.

When someone writes a history of notable first law officers since 1901, it’s unlikely to include a chapter on Mark Dreyfus who, by the way, like a lot of supposed republicans, calls himself KC rather than SC.

Dreyfus is by no means the worst attorney-general — the Morrison Government’s Michaelia Cash probably holds that title — but he is in the second division.