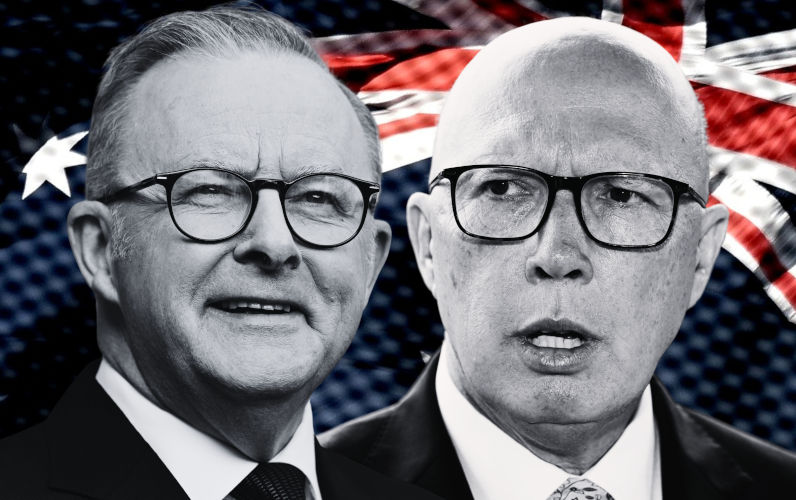

Election 2025: the Labor-Liberal waltz of irrelevance

May 5, 2025

Another federal election. Another Labor Government with a much enhanced majority. A campaign with no great convulsions, except for the Liberal debacle. An Opposition Leader conceding defeat with proper decorum. All must be well in the land of Oz. But all is not quite as it seems.

Seldom have Labor and Liberal been so visibly disconnected from a rapidly transforming world. Never before has the lack of public interest in a national election and the electorate’s mistrust of parties and politicians been so palpable.

In the 1946 federation election, the two major parties together secured 93.3% of the total vote. Three years later, that figure rose to 96.2%. In 2025, they may secure 66% of the vote. The two parties supposedly focused their policy pitch on the cost of living. Hence, the endless election promises on housing, energy and medical bills, cost of education, tax cuts and more.

However, these promises, even if implemented, will do little to ease the pain of those in greatest need. They are palliatives that may relieve the symptoms for a while and, even then, only for some. They will do little to cure the ailment.

What is the ailment that neither party dares address? It is called inequality, the taboo word in Labor and Liberal parlance. In 2019-20, the 10% of Australian households with the highest incomes averaged weekly earnings of $5248 per week after tax, compared with $631 for the lowest 10%. In 2022-23, the richest 10% of households held 44% of all wealth, 126 times that of the lowest 10%.

To add insult to injury, the land of the “fair go” is now home to some 150 billionaires, each making $67,000 an hour, while more than two million Australians experience severe food insecurity.

How much of this is likely to change under the Albanese Government?

Another wound in the nation crying out for action got the same cold shoulder. The enduring pain of First Nations was met with stony silence, as was the Voice referendum fiasco, to which both parties contributed in no small measure.

Rather than seek ways to heal the festering wound, party leaders relegated the question to the too-hard basket. The prime minister, in effect, suspended further consideration of the Makarrata Commission, truth-telling and treaty-making.

The signal coming through loud and clear is that we are back to John Howard’s policy of “practical reconciliation” to which successive Liberal governments have clung, and in which an Albanese Government is now hoping to find refuge.

The disturbing levels of drug and alcohol abuse have been met with the same apparent indifference. One in six Australians has a drug addiction and one in ten an alcohol addiction, which means some two million Australians suffer from substance abuse.

The mental health packages by Labor ($1 billion) and Coalition ($900 million) to be expended over the next several years may make it easier, especially for young people, to access free mental health treatment. They do not, however, address the underlying economic, social or cultural factors driving the mental health epidemic.

The election campaign has been equally notable for its scant treatment of our climate change predicament, the biodiversity crisis, and other looming environmental threats. The attention devoted to the rise of far-right extremism or our dysfunctional mainstream and social media has been conspicuous by its absence.

What this tells us is that contemporary Australian politics is in the grips of a pervasive cognitive and moral myopia. Politicians, the major political parties and the institutions of the state, seem strangely unable to focus on the nation’s ills, other than by way of expedient short-term remedies and soothing reassurances.

Hardly surprising then that our political elites, and the security establishment which advises them, should be so detached from the momentous transition in world affairs. Yet, the writing is on the wall.

For many decades, America’s global supremacy has been the bedrock of Australia’s alliances and military planning. But that supremacy is long since gone.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the US ran either a surplus, or a small trade deficit. A large deficit became the norm in the 1980s and 1990s, and by 2022 this reached a staggering $944 billion. In 1960, the US economy accounted for 40% of the global economy – by 2019 its share had fallen to 24%.

Much the same can be said for the leading Western economies. The G7 share of the world economy declined from a high of 67% in 1992 to 44% in 2022. Even more striking has been the decline in Japan’s share, from a high of 17.8% in 1994 to 3.6% in 2024.

These trends help explain the steady loss of US economic dominance mirrored and exacerbated by the steady decline of the West’s collective economic influence.

The converse trend has been China’s equally dramatic ascent. Since 2014, China has been the world’s largest trading nation, and since 2016 the world’s largest economy when measured by purchasing power parity.

Reinforcing this trend has been the performance of the fast-growing economies of Asia, notably India, Vietnam and Indonesia, and the rise of the BRICS group, now a considerable political force intent on creating a counterweight to the West’s global influence.

As one author has observed, “we are witnessing the unravelling of the global order… a period in history that bridges a fading industrial era dominated by Western countries and a new digital era underwritten by the rise of China and a vast Asian trading system".

A remarkable economic and geopolitical power shift is now in full view, but not, it seems, in the sight of the two major Australian political parties. And the shift we are presently witnessing may be even more profound.

The West-centric world, in which first Europe, and then the United States, held sway, is steadily giving way to a new world in which other civilisational centres and their rich histories, traditions and languages are emerging or re-emerging.

The centre of cultural gravity is visibly shifting from the West to the East, from Occident to Orient.

The Trump phenomenon is a manifestation of this shift. Trump’s rallying cry “Make America great again” says it all. American supremacy belongs to yesteryear.

In early April, Trump’s America chose to put on a tantrum by unleashing an unsustainable trade war on the rest of the world. A month later, the exorbitant tariffs indiscriminately imposed on rich and poor, friends and adversaries alike, had to be drastically rolled back.

China remains the exception, with 145% tariffs on Chinese goods still in force. But not for long. This is a war the US economy cannot win.

The Liberals were hardly expected to offer any useful observations on any of this. But what does Labor see as the strategic, economic and cultural implications for Australia?

How will the Labor Government meet the challenges ahead? How will it respond to the gruesome reality of genocide that has reared its ugly head once again? What of the seeming paralysis of the United Nations, and the blatant disregard of international law? With whom will it consult and collaborate?

And, closer to home, what of Australia’s outmoded and divisive Anglophone military alliances and entanglements and costly military procurement projects of dubious value? A host of questions the election campaign conveniently swept under the carpet.

If risks were ignored, so were the opportunities that beckon. Asia’s ascent and America’s decline, coupled with Australia’s rapidly changing cultural profile, constitute a unique moment for the nation to shed its colonial mindset, recognise the sovereignty of First Nations, and reset its sense of place in the world.

Election 2025 does have a salutary message. Neither Liberal nor Labor is up to the task. The country’s political institutions are in a state of atrophy. Those yearning for leadership and initiative will need to look elsewhere.

Civil society — with its imaginative social movements, far-seeing advocates, independent publishers, and public-spirited and culturally diverse unionists, educators, artists, writers and philanthropists — offers a more promising avenue.