Environment: Australia’s exported fossil fuel emissions are treble our total domestic emissions

May 4, 2025

Australia’s exported coal and LNG produce three times more emissions than 27 million Australians. The US wastes prime agricultural land to inefficiently produce energy for cars. Shed snake skin protects young birds. Kosciuszko benefitting from fewer feral horses.

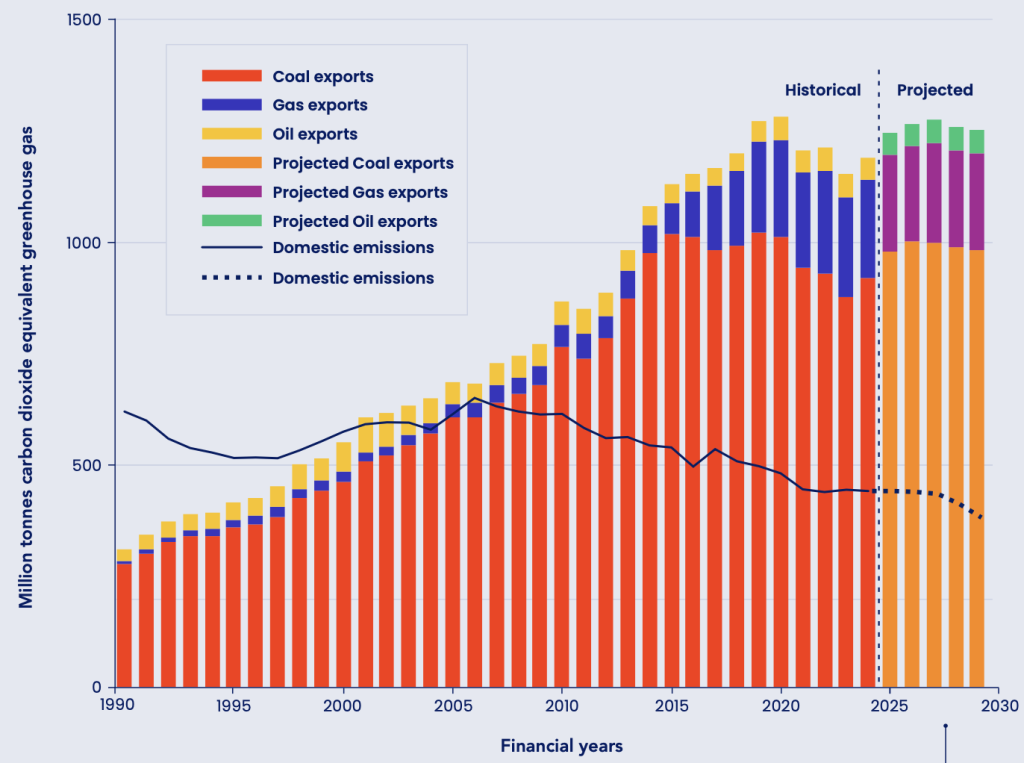

Australia’s exported fossil fuel emissions overwhelm our domestic emissions

In 1990, the greenhouse gas emissions generated from the fossil fuels (mainly coal) that we exported were roughly half of Australia’s total domestic emissions. In 2024, our exported fossil fuel emissions, still mainly coal-related but with gas (LNG) making a substantial contribution, were almost three times our domestic emissions (see figure below). Domestic emissions had fallen by almost 30% during the intervening 34 years but exported emissions had roughly quadrupled. Exported emissions are projected to stay about the same for the next five years.

Although Australia’s domestic emissions may decline a little between now and 2029, it’s worth noting that the actual production of fossil fuels consumes a lot of energy and produces a lot of GHGs, currently at least a fifth of Australia’s total domestic emissions.

US’ 21st century corn laws

Corn is the US’ largest crop. Every year, the country produces about 350 million tonnes, nearly a third of all the corn grown on Earth. The crop covers 364,000 square kilometres, about 1.6 times the size of Victoria. Yessiree, Americans love their corn.

Or at least, they love growing it. They don’t eat that much: 10% of the crop goes into sweeteners and starches for human consumption, but 60% feeds animals. The remaining 30% goes into producing the ethanol that, by law, must constitute 10% of gasoline. That’s the equivalent of two Tasmanias of prime US farmland growing fuel to put into motor vehicles. It’s almost three times as much land as the US devotes to growing fruit and vegetables.

However, ethanol contains two-thirds as much energy as petrol. So those two Tassies supply just 7% of the US’ energy for motor vehicles. Growing corn to gather CO2 and oxygen and photosynthesise it into ethanol is a very inefficient way of capturing the sun’s energy. Over a year, one hectare of solar farm produces as much energy as 100 hectares of corn.

Growing corn and producing ethanol is not at all environmentally friendly: farm and factory equipment use fossil fuels, fertilisers are produced from fossil fuels, toxic insecticides and herbicides are sprayed on the corn, polluted water runs off into the creeks, and topsoil is lost when the earth is bare between crops.

Actually, to say that farmers like growing corn is not the real story. What they like are the billions of dollars of government tax breaks and subsidies they receive for the 30% of the crop for which they can’t find another buyer – grants that both Republican and Democrat parties, governors and presidents have been strenuously supporting for 20 years.

It would seem to make sense for corn farmers to turn 1% of their property over to solar farming and use the other 99% to grow something more useful than corn, for instance, plantations to save native forests or natural fibres to reduce the demand for synthetics produced from petrochemicals. Or they could harvest carbon or rewild the area. They might even mix solar panels and crops on the same patch of land (agrivoltaics).

So, Elon, what about turning DOGE’s attention to this? How about ending government support for the very costly, energy-inefficient, environment-destroying production of corn to power (non-electric) vehicles? You could save the government bushels of money and use some of it to help farmers transition from corn to solar farming. Maybe I’m confused, though. Maybe an undeserving migrant’s social security handout is evidence of government inefficiency whereas an Iowa farmer’s corn-growing subsidy is making America great again.

(For 30 years, in the first half of the 19th century, British political debate returned repeatedly to the Corn Laws – should they be repealed or not? The Corn Laws were tariffs and import barriers on overseas cereals that were designed to keep prices high for domestic farmers. Inevitably, their presence/absence was closely linked to a wide range of other domestic and international issues and they were highly contentious.)

Shed snake skin protects (some) birds’ nests

It has long been observed that some birds like to use shed snake skin in nest construction, even though, unlike grass, leaves, sticks, mud, animal fur or even spiders’ webs, it is not very common. However, neither which particular birds use snake skin nor why have been well researched,. For instance, does snake skin confer any reproductive advantage and, if so, is it because it prevents predation or protects nests from harmful parasites or microorganisms?

New evidence suggests the habit is pretty much limited to small birds in the passerine group (birds that vaguely resemble sparrows). Within the passerines (which includes 60% of all bird species), it is much more common among species that build cavity nests than those with open cup nests. The reason seems to be that the presence of shed snake skin reduces the predation of eggs and chicks in cavity nests, but not open cup nests.

Explanations of these three photos can be found here.

The researchers noted that while a wide range of predators of various sizes visited open cup nests, a narrower range of mostly small-bodied mammal predators visited cavity nests, presumably for obvious reasons of access. Small animals are themselves often preyed on by snakes and it was hypothesised that shed snake skin emits an odour that warns them off.

The research illustrates the complexity of the ecological factors that facilitate evolution. In this case, the size of the bird (small birds are less able to defend their nests themselves), the “enhanced cognitive capacity of passerines” (it seems that sparrows are smarter than galahs – who knew?), the shape of the nest, the characteristics of the local predators and, of course, the presence or not of snakes have all interacted to influence the development of this nest-building behaviour, which itself influences the species in the bird’s ecosystem and their behaviours. Evolution and the development of traits within individual species is not a one-way process.

How to rehabilitate an open cut mine. NOT

Last week, I discussed a conference about open cut coal mining and so-called biodiversity offsets in the Leard Forest area of NSW near Narrabri. On the Sunday morning, the conference organisers led a tag-along drive around the local mines, at times under the watchful but non-confrontational eye of the mines’ security officers. What we saw was shocking. The destruction of the land by open cut mining is extensive and total (if you haven’t seen open cut mines for yourself or seen photos, just search for “Australian open cut mine images” or go here).

Once there’s nothing of value left for them to extract, mining companies are keen to promote their commitment to mine rehabilitation. Often, however, what the mines do, and call “rehabilitation”, is absolutely laughable: smooth over a hill of (to them) worthless earth and rocks, cover the spoil heap with top soil, sow some grass seeds, plant a few trees and, hey presto, original ecosystem restored, no lasting damage done. Wrong! Just because an artificial, reconstructed topography has been covered in grass does not mean that the original ecosystem has been restored or ever will be.

To illustrate the joke, mining companies are now aware of the value of habitat trees, large, old or even dead trees that have lots of hollows that support incredibly diverse arrays of animals, plants and microorganisms. I took the picture below of an allegedly rehabilitated area on one of the Narrabri mines. The eight or so mast-like dead tree trunks that you can see have been stuck in the ground by the mine and are now laughingly referred to as habitat trees.

Kosciuszko recovering from feral horse damage

I’m delighted to report that the NSW Government’s policies of removal and aerial culling of feral horses in Kosciuszko National Park is delivering a two-fold success. First, the number of these destructive pests has been reduced from an estimated and booming 17,000 a few years ago to 3000 to 4000 now. Second, the vegetation in the National Park is starting to recover where the ferals have been removed.

The pictures below (taken near the source of the Murrumbidgee River) were kindly provided to me by the Invasive Species Council who have worked for years to build public support for the removal of the horses and advocate for stronger action by the NSW Government. The remaining step is to get the ridiculous and ridiculously-named Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act 2018 repealed.