Environment: Nations ignoring the need for a just transition to zero carbon

May 18, 2025

Eliminating greenhouse gas emissions is dangerously slow, but doing it in a fair, just and inclusive manner is all but non-existent. Climate change’s many harmful outcomes for women and girls includes more child marriages. Fishing doesn’t have to kill mammals and birds.

What is a just transition? Is anyone doing it?

“A 'just transition' refers to addressing climate change in a fair, just and inclusive manner. This means creating decent work opportunities for all, avoiding risks like unemployment and displacement, and taking an inclusive approach to managing challenges associated with the low-carbon transition. It seeks to balance the risks and benefits fairly, leaving no one behind.”

In Australia, our minds tend to jump first of all to coal mining and coal-fired power station communities and ensuring that workers, communities and regions are helped to deal with closures. But a just transition is not just about jobs and economies. Particularly in developing countries, it might also include issues such as sex discrimination, land rights, health concerns, air pollution, land restoration and water access. Different countries have different transition challenges that require different responses.

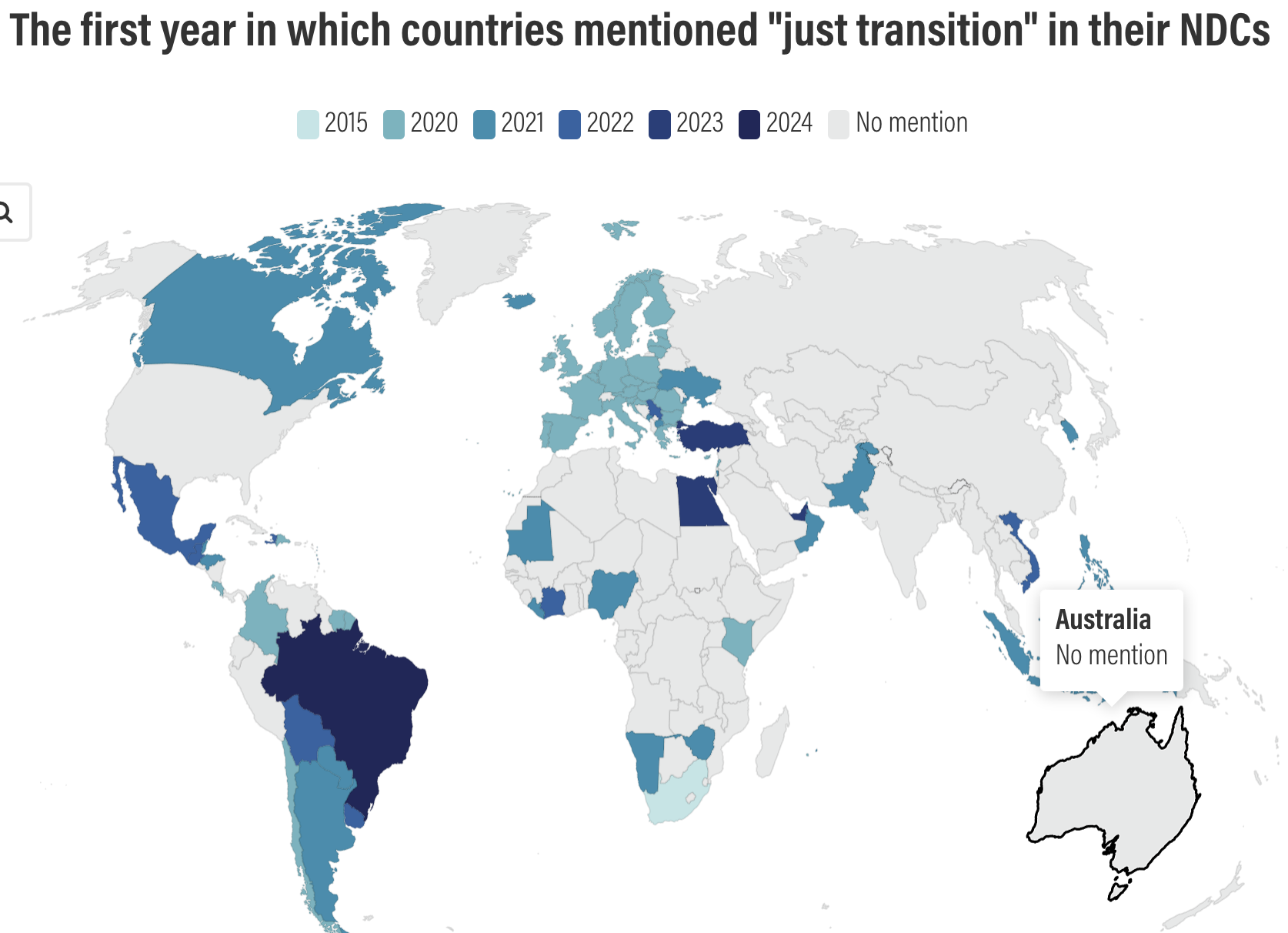

Although the idea had been around for a while, just transition gained prominence when it appeared in the 2015 Paris Agreement. It’s a pretty crude measure of the extent to which countries are taking just transition seriously, but the map below indicates the year in which countries first mentioned a just transition in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that they are required, as signatories to the Paris Agreement, to submit to the UNFCCC. Europe and the Americas (with the not surprising exception of the US, a nation not noted for its emphasis on equity) have made a start but the rest of the world has largely been slow to respond.

Just transition discussions tend to focus on what occurs within national borders but just transition also has major inter-nation dimensions arising from past and present colonisation and exploitation of nations’ natural resources and people. A significant barrier to economic and social development in nations of the Global South is their debt repayments – a burden arising from the global financial system that was created by, and benefits, rich countries, the same ones that have caused climate change. If wealthy nations are serious about a just transition, they must not only stop funding and benefitting from the ongoing extraction and burning of fossil fuels, but also stop extracting debt repayments from poor countries and stop blocking reform of the financial system – i.e., end climate colonialism. There will be an opportunity to start developing a new international financial framework at the UN Financing for Development conference in Seville in June. Don’t hold your breath.

Another dimension of climate injustice that transcends national borders is the obscenely high levels of greenhouse gas emissions of wealthy people (more due to their investments than their luxurious private-jet-setting lifestyles) compared with not just the absolute poorest people around the world, but almost everyone else. Of the 0.61oC of warming that occurred between 1990 and 2020, the emissions associated with the wealthiest 10% were responsible for 65%, the wealthiest 1% for 20% and the wealthiest 0.1% for 8%. If the entire world had emitted like the top 10% during those 30 years, the warming would have been 2.9oC. If like the top 0.1%, 12.2oC. If everyone had had the emissions of the poorest 50%, there would have been almost no additional warming.

The most affluent 10th of the world’s population have caused climate change. They (we!) suffer least from it and are most able to avoid and handle the problems that do arise. A just transition demands that these inequities be eliminated.

Anglers, please consider our birds

Angling and birdwatching are two of Australia’s favourite recreations, especially since COVID. Unfortunately, many seabirds and waders get entangled in fishing line and hooks that have been cut loose and left by fisherfolk when their line gets snagged in the water or nearby vegetation.

About 90% of the injuries suffered by seabirds and shorebirds are caused by discarded fishing tackle. A few birds are rescued and taken to vets, but most suffer, maybe losing a leg, drowning, succumbing to predators or simply starving to death. If a bird has a tangle of line and hooks attached to it and then wanders through a beach nesting colony, it can snare the legs and wings of multiple chicks, leading to a mass death. Swallowing a lead sinker can result in heavy metal poisoning. And it’s not only coastal birds that suffer, inland birds can also become tangled in lines and hooks on lakes and rivers.

The death of a few Silver gulls may not have much effect on population numbers, but for threatened species, such as Hooded plovers and Eastern curlews, it can be disastrous.

Here are some tips for anglers and fishing clubs to consider:

- Avoid fishing near bird feeding and breeding areas;

- Clean fish away from the water’s edge to avoid attracting birds;

- Dispose of scraps in the bin, not the water, so that birds aren’t attracted;

- Use environmentally-friendly fishing tackle;

- Don’t simply cut and leave entangled line in the water or at the water’s edge. Retrieve your (and anyone else’s) tackle and reuse it or dispose of it responsibly; and

- Wrap up discarded tackle before putting it in the rubbish bin or better still a dedicated fishing tackle bin.

(With thanks to John Peter for his article in the Summer 2024 edition of Australian birdlife.)

Climate change increases child marriage

As we all know, climate change causes extreme weather events such as heatwaves, bushfires, cyclones, floods and droughts which have flow-on effects that cause food shortages, poverty, community and international conflict and short- and long-term displacement of populations. These can all cause or increase gender-related discrimination and violence, including sexual assault and disruption or cessation of girls’ education.

“Women living in poverty are the most affected by the devastation caused by the fossil fuel industry. Women bear the brunt when fossil fuel projects lead to rising food and water insecurity, increase women’s unpaid labour, and increase gender-based violence and HIV infection rates. When climate disasters hit, women and their children are 14 times more likely to die, and four times more likely to be displaced. For women on the frontlines of fossil fuel extraction, coal, oil and gas projects can entrench existing inequalities and further curtail their rights.”

In 2024, 242 million children in 85 countries had their education interrupted by extreme weather events. In a situation where about 60% of child brides have received no formal education and girls with only primary school education are twice as likely to marry young, climate change exposes even more girls, sometimes as young as 12, to child marriage.

Girls and young women face an increased risk of sexual assault when they are in temporary shelters for displaced families and refugee camps. In societies where having been sexually assaulted is stigmatised, this can result in early marriage.

The potential to receive a dowry can also be an incentive for a poor family to marry off a child or teenager.

Girls who are married before 15 are 50% more likely to suffer partner violence and are much more likely to have complications during pregnancy and childbirth, including death of the mother and/or infant. Child brides are also more likely to be isolated and have depression and anxiety.

Adding to the problem is that countries where child marriage is relatively common, for instance across north and central Africa, are also ones that are highly exposed to the effects of climate change.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals aim to end child marriage by 2030, but countries’ responses to the issue are extremely variable. The problem is complex, being influenced by societal gender norms, but essential elements of a response include tackling poverty, establishing and enforcing a legal minimum age for marriage, and, extremely importantly, ensuring that girls receive a high-quality education in terms of content and duration.

Bycatch kills thousands of European whales and dolphins

At least 35,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises die each year in European waters from the Black Sea to the Arctic by becoming entangled in commercial fishing gear. Gillnets, static linear nets anchored to the bottom, and driftnets which hang in the water, but are not anchored, are the major causes. The loss of life is further threatening five ocean mammal populations that are already recognised as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable. And this is just in European waters.

The problem will only be reduced when governments develop, implement and monitor bycatch action plans that, for instance, require the use of less harmful fishing gear and change the times of the day and the places that commercial fishing occurs.

Women suffer most from climate change

Halimo Ahmed Yusuf from Somaliland is a pregnant 45-year-old mother of nine:

“Drought affected us on many sides – whether it is the livestock or the production of a business. I used to own 25 cows and now 20 of them are dead. We have no farms or other sources of income. We are pastoralists and drought took the lives of our livestock. We don’t have any other production.”

Fathiya Muhamed Hassen is also from Somaliland.

Projects to empower women can change family and community attitudes and resilience.