The Racial Discrimination Act at 50

May 10, 2025

The passage 50 years ago of the Racial Discrimination Act, Australia’s first substantial piece of human rights legislation, laid the basis for the recognition of native title in the common law in the 1990s.

In 1966, the Holt Government signed the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. In the following year, the Australian people voted overwhelmingly for the Commonwealth to have a “races power”, i.e. “power to legislate for the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws”. But between 1966 and 1972, the Commonwealth was unable to ratify the CERD because some states continued to discriminate against Indigenous people. The Commonwealth’s legal officers advised the government that the new “races power” would be insufficient to forbid discrimination between races.

The Whitlam Labor Government, elected in 1972, took a much more urgent approach to signing and ratifying human rights treaties and passing legislation to improve the lives of Aboriginal people. Whitlam set up the first independent Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs and increased federal appropriations in such areas as health, education and housing.

He also took active steps to ratify the CERD by encouraging Queensland to remove its discriminatory legislation. Frustrated with Queensland’s lack of action, Whitlam and his attorney-general, Lionel Murphy, decided to use the “external affairs” power of the Constitution as the basis for its Racial Discrimination Bill, predicting that the states would challenge the legislation in the High Court. On Murphy’s reasoning, the Commonwealth would be able to legislate important obligations incurred by Australia under international conventions by national legislation applicable throughout all of Australia subject only to any relevant constitutional prohibition. This reasoning aligned with former Labor leader, H.V. Evatt’s, views of the Constitution. It was rejected, however, by many lawyers and politicians, including premiers Charles Court and Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

On 31 October 1975, the Racial Discrimination Act passed both houses of Parliament. It purported to bind the states and was also drafted to override any state legislation that may have been inconsistent with the aims of the CERD. With it, Australia’s first substantial human rights legislation came into effect.

Several years later, in 1982, the legislation was tested in the High Court as Murphy had predicted. The case concerned the attempt of an Aboriginal man, John Koowarta, to purchase a grazing property in Queensland on behalf of a group he represented. The Queensland minister for lands refused to permit the sale because state policy forbade Aboriginal groups purchasing large areas of freehold or leasehold land. Koowarta argued that the Bjelke-Petersen Government’s actions were discriminatory, while the state argued that the Racial Discrimination Act was unconstitutional.

The High Court, now with Murphy sitting on the bench, was split over Koowarta’s challenge, but eventually decided narrowly in his favour. It ruled that the races power did not justify the legislation, but that the act could be upheld by the “external affairs” power insofar as the legislation was giving effect to an international convention, signed and ratified by the Commonwealth Parliament. The High Court thus confirmed that the Commonwealth Parliament could enact national human rights laws binding on the states.

When Hawke came to power in 1983, the Australian Labor Party’s platform included a commitment to securing national land rights for Aboriginal people throughout Australia. The ALP’s ambition was to build on land rights established by Whitlam in the Northern Territory. The project to establish uniform land rights legislation was, however, frustrated by opposition from the Western Australian Labor Government.

Nevertheless, Indigenous Australians did obtain a different kind of land rights in the early 1990s through the High Court’s Mabo judgment. This did not involve the grant of interests under Commonwealth or state legislation, but rather recognition under the common law of the pre-existing rights and interests of Indigenous people in relation to land and waters.

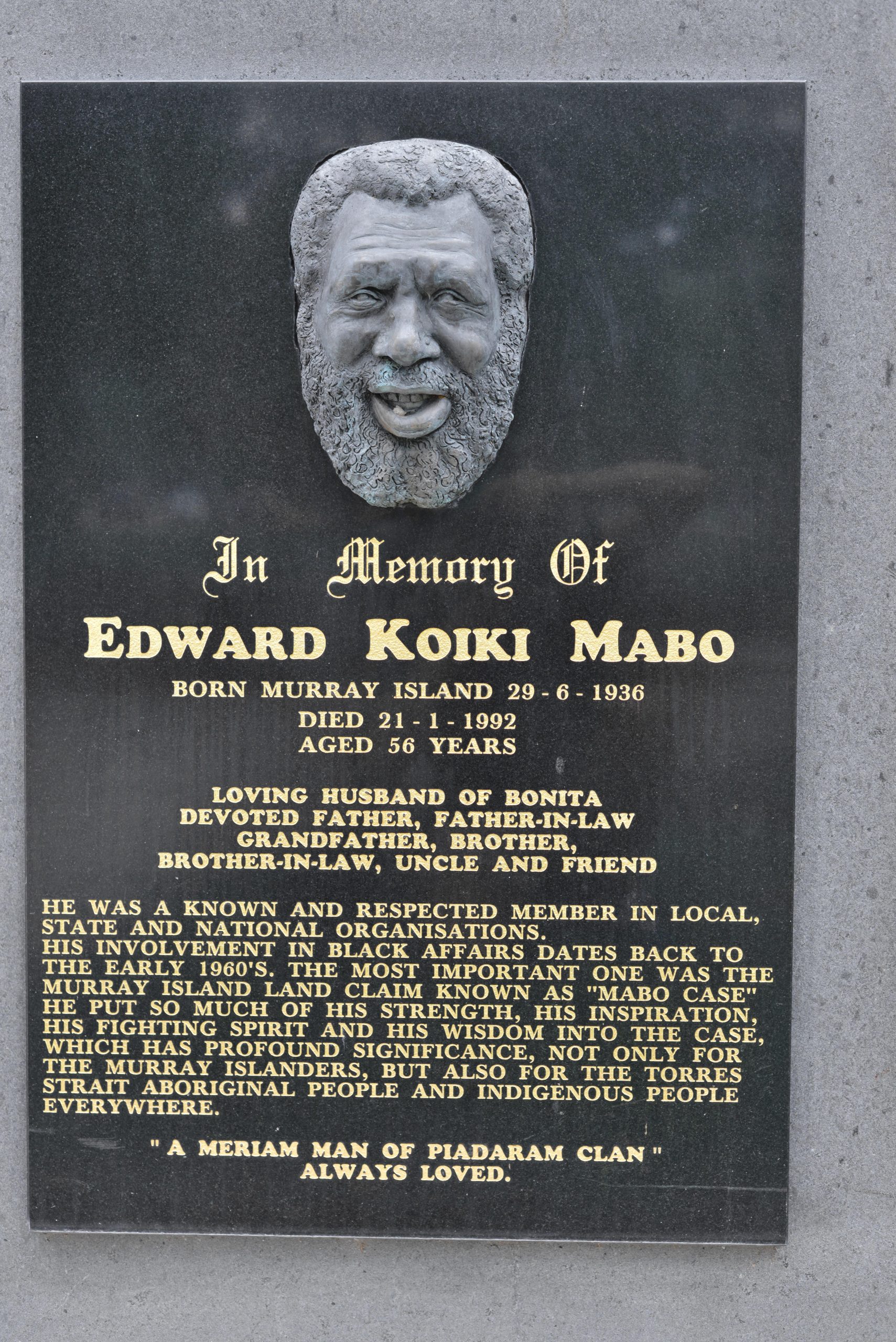

Labor’s use of the external affairs power to pass the Racial Discrimination Act was essential to Indigenous Australians winning recognition of native title rights to land and water. Indeed, but for the Racial Discrimination Act, the native title revolution would not have taken place. When Eddie Mabo, in the early 1980s, sought to prove native title rights for Murray Islanders in the Torres Strait, the Queensland Government moved retrospectively to quash any native title rights that might exist by passing the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act.

Mabo’s lawyers, led by Ron Castan, argued successfully that the Coast Island Act was invalid because it was inconsistent with the Racial Discrimination Act. In 1988, most of the High Court agreed and Eddie Mabo’s lawyers were thus able to proceed to argue the larger case for native title. On 3 June 1992, the court rejected the legal doctrine that Australia was terra nullius (land belonging to no one) at the time of European settlement. It also held that the common law recognised a form of native title where Indigenous people had maintained their connection with the land and where the title had not been extinguished by acts of imperial, colonial, state, territory or Commonwealth governments. Later, in 1993, when the Western Australian Government passed legislation to quash the Keating Government’s Native Title Act, a legislative framework for managing native title claims, the High Court unanimously held the Western Australian law to be inconsistent with the Racial Discrimination Act_._

But for Whitlam’s use of the external affairs power, there would have been no Racial Discrimination Act and without this Act, the Mabo judgment of 1992 would have been impossible. The RDA thus remains, at 51, one of the most consequential legislative achievements of the Whitlam Government.