Water is a vital part of population policy

May 17, 2025

If ecological sustainability must be the basis for population policy, as argued by Jenny Goldie, then a vital ingredient for sustainability is water – the essence of life.

If population policy requires identifying a desirable population size for Australia in the future, we must consider whether there will be enough water to support it. Official projections show Australia will grow from 27 million to 40 million people inside 40 years. Some see this as just a staging point on the way to much larger numbers, aiming for 50, 70 or even 150 million people. There has been surprisingly little discussion about water requirements to support these numbers, despite Australia being the driest inhabited continent with the least run-off and most variable rainfall. Recently my colleagues and I explored this question in a report entitled Big Thirsty Australia.

Water austerity can only go so far

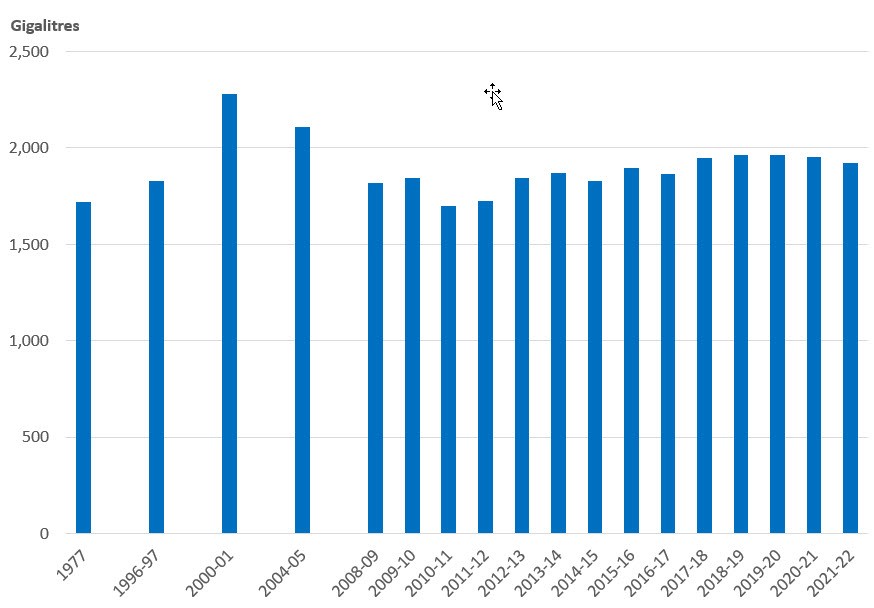

Since 1977 Australia’s population has doubled in size. Household sector water usage rose steadily with population up to the turn of the century, but then fell sharply before rising again over the past decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Household sector water use 1977 – 2022

Source: ABS Water Accounts; Klaassen, B. (1981). Estimated annual water use in Australia. Water. The official journal of the Australian Water and Wastewater Association, vol. 8 no. 1, pp. 25-26.

The reason for the initial decline is the Millennium drought (1997-2010), accompanied by a decade of major reforms of water governance and public messaging encouraging water frugality, resulting in large improvements in water efficiency. Lower per person water use has been achieved through water restrictions during prolonged drought, increased water prices, more efficient technologies, public education, more apartment living and smaller gardens.

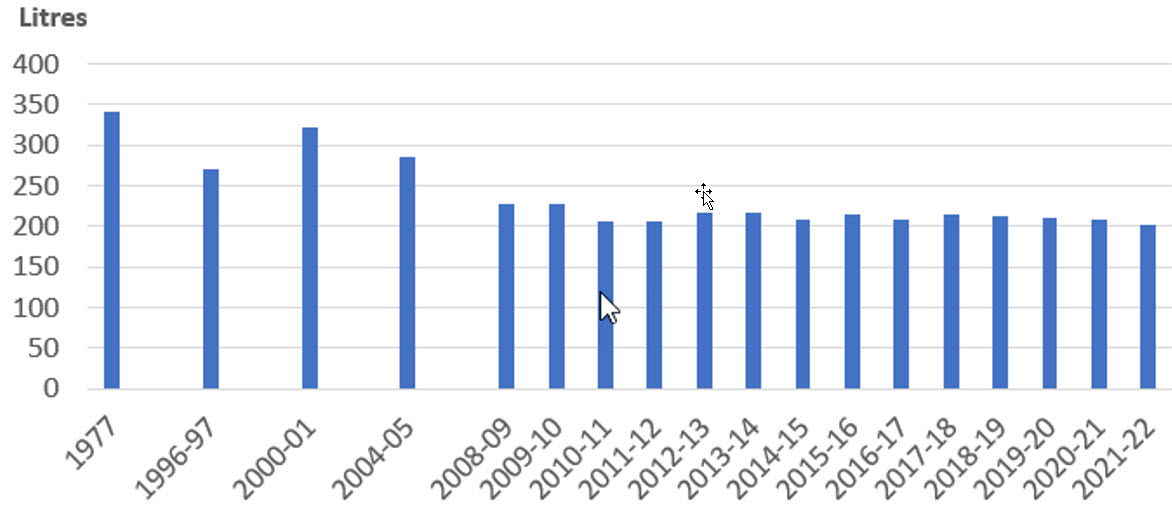

However, the low-hanging fruit for water saving have now been picked. The rise in water use after 2010-11 is probably due to the sharp rise in net overseas migration from about 2007 onwards (averaging 226,000 per year from 2007 to 2019). Average per person water use in the household sector has, in the meantime, flatlined at about 200 litres per day (Figure 2), meaning that adding more people will add more water demand. As water authorities acknowledge, future increases in demand, driven by population growth, must largely be met by augmenting supply.

Figure 2. Daily per capita water use in the household sector, Australia 1977 – 2022

Source: As for Figure 1.

Additional supply means costly ‘manufactured water’

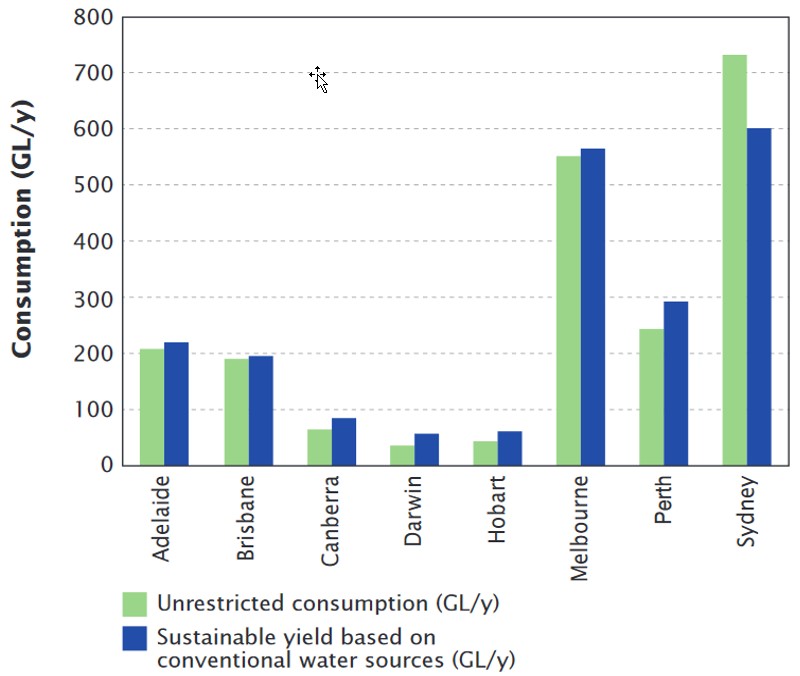

The turn of the millennium was coincidentally the point at which water demand in many Australian cities reached or exceeded what could be supplied reliably by conventional means, namely rainfall, streamflow and groundwater (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rain-dependent water supply versus consumption in capital cities in 2002

Source: Burn, S. (2011) Future urban water supplies, Ch 7 in Water: science and solutions for Australia. Prosser I. (ed), CSIRO: Canberra.

Big water infrastructure built last century was reaching its limits. With no more sites for big dams near urban centres, and facing an extended drought plus a drying climate, state governments opted to commission large-scale desalination plants in most mainland capital cities, starting with Perth’s first plant in 2006. Though controversial due to cost, they were also a politically convenient techno-fix that deferred asking the hard questions. Since the 2017-19 drought, greater use of desalination as a source of “manufactured” water is now normalised in the planning of most urban water authorities. Melbourne Water, for example, envisages 80% of its supply coming from desalination and recycling by 2070 (with a projected population of 10-12 million) compared to 35% now.

Climate change adds more risks on the supply side. Studies predict hotter, drier and more extreme conditions in southern Australia, particularly around major urban water catchments. CSIRO water expert Francis Chiew says multi-year droughts “will become more frequent and severe, and the reliability of water supply will significantly reduce”. Recent studies of Australia’s climate over the past 2000 years suggest that, even prior to human-caused climate change, the continent had already experienced extended megadroughts more severe than any encountered during the 20th century. There is evidence of megadroughts lasting as long as four decades. What we have assumed as normal in the 20th century is atypically high compared to the longer history.

Urban water authorities anticipate further population growth will require adding anywhere from 850 gigalitres (GL) to more than 1450 GL of new annual water supply to mainland capital cities over the next several decades. For comparison, 1450 GL is around the total volume of water currently supplied each year for Sydney, Melbourne and Perth combined. That would mean deploying another 17 to 29 50 GL desalination plants. With Perth’s latest plant costing $2.8 billion (including a 33.5km connecting pipeline), the capital cost of this build-out would be $47–$81 billion in today’s money, before considering running costs and environmental impacts.

Some of this manufactured water might be supplied by potable water recycling instead of desalination – both use the same reverse osmosis technology and both are more energy intensive and at least twice as costly as conventional sources. However, although implemented in Perth via aquifer recharge, potable reuse faces problems of public acceptability in eastern Australia, despite there being a sound scientific basis for its safety. Although water professionals are favourable to reuse technology, politicians are not, and it may only gain public acceptance once a dire water supply crisis is evident.

Using desalination to support ongoing population growth is maladaptive in terms of cost, site availability, additional energy demands, greater complexity, and vulnerability to threats such as sea level rise. Water costs for consumers would rise steeply: one estimate is for a real six-fold increase by 2067, with serious implications for equity.

Desalination is presented as “sustainable” because it can be powered by renewable energy. However, it converts a water supply problem into an energy supply problem. It’s not helping sustainability if extra renewable capacity is used to meet the extra energy demand from desalination, rather than displacing existing fossil fuel use in other sectors.

Population policy is water policy by default

Water authorities and ministers are turning to desalination technology to prevent water being a constraint to population growth. In doing so it becomes an enabler of further growth, which externalises wide-ranging negative impacts into other parts of the social-ecological system. Cramming an additional 13 million people into Australia’s largest cities cannot avoid affecting the surrounding biodiversity, particularly through further land clearing for greenfield development, greater demand for goods and services produced in the hinterlands, and more recreation and tourism pressures. Desalination and recycling can do little to water the drying hinterlands outside urban centres.

The Productivity Commission’s National Water Reform 2024 report recognised Australia faces a “significant water investment challenge” and argued strongly for considering all options for water security, “even those that are politically difficult”. It further argued against “policy bans” on particular options “without due consideration of the actual costs and benefits”. Yet the Commission’s omission of population policy among the options is itself a policy ban.

While desalination and recycling are valuable technologies to compensate for unavoidable impacts of climate change on water supplies, it is irrational to impose extra costs and vulnerabilities to cater for avoidable population growth, when no benefits of a larger population are evident to justify these (and many other) extra burdens. The prospect of droughts lasting decades, in an Australia with a much larger (and still growing) population, is a recipe for disaster. Stabilising our population size is by far the cheapest, simplest, greenest and safest way to guarantee Australia’s water security.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily of SPA.