Chalmers hints at more tax reform – What should we do first? Part 2

June 23, 2025

In the second of a two-part series Saul Eslake looks at what the top priorities for tax reform should be.

Some — especially business groups — argue that Australia’s company tax rate should be cut in order to improve incentives for investment.

It’s true that Australia’s statutory company tax rate of 30% is relatively high by international standards. But because of Australia’s dividend imputation system, any reduction in that rate would, for Australian shareholders (including Australian superannuation funds). be offset by an increase in the rate payable on their dividends. The only beneficiaries of a cut in the company tax rate would be companies which retain most or all of their earnings rather than paying out dividends, foreign shareholders in Australian companies (who aren’t eligible for imputation credits), and wholly-owned foreign companies operating in Australia. It’s far from clear why they should get a tax cut.

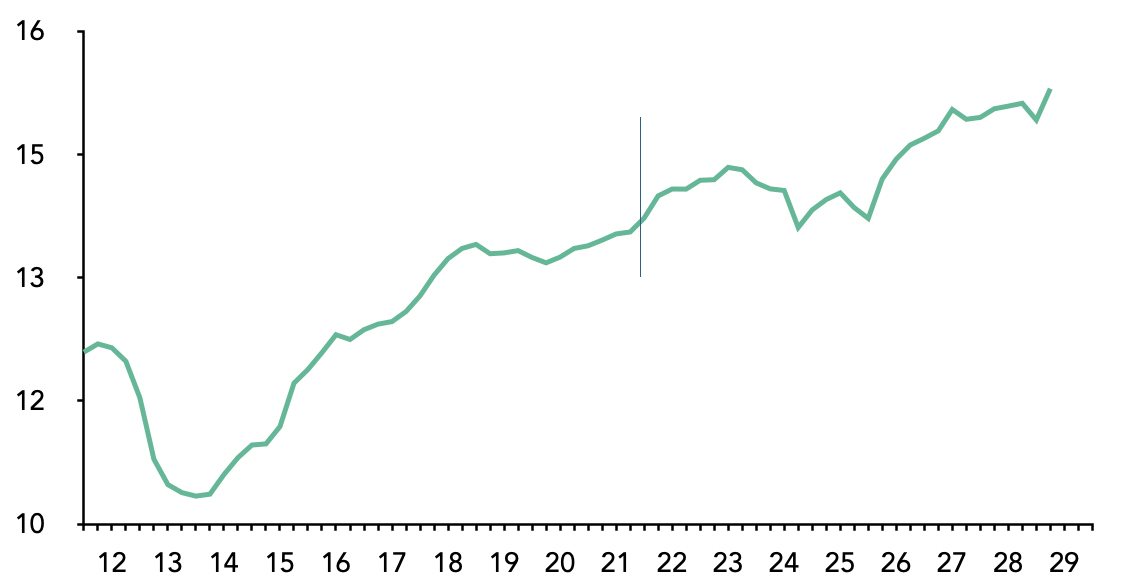

Moreover, international evidence suggests that cuts in statutory corporate tax rates in recent years have done little to stimulate business investment. As shown in Chart 4, the cut in the US corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, instituted from the beginning of 2018 during the first Trump Administration did not prompt any significant increase in business investment – which had been rising steadily from its post-GFC lows over the preceding eight years.

Chart 4: US business investment as a percentage of GDP

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Gross Domestic Product, 29th May 2025.

That conclusion is reinforced by a survey of the econometric evidence on the impact of the Jobs and Tax Cuts Act 2017 published in April this year by the US Congressional Research Service. Rather, the Trump corporate tax cuts prompted a surge in corporate share buybacks, and hence in senior executive remuneration.

Likewise, corporate tax cuts in Canada and the UK do not appear to have had any appreciable effect in boosting business investment (and the UK corporate tax cuts were largely reversed by the previous Conservative Government in 2022).

That’s not to say measures to boost business investment would not be appropriate. On the contrary, as recently published research by the Reserve Bank has shown, slow growth in business investment over the past 15 years has contributed to growth in labour productivity.

But tax reforms specifically targeted at incentivising increased investment — such as accelerated depreciation or “instant” asset write-offs — are more likely to produce that outcome than cuts in the company tax rate.

The task of budget repair would also be aided by reforms directed towards more effectively taxing economic rents, including from fossil fuel exports as advocated by Ken Henry and Ross Garnaut. Despite the attempts during the Albanese Government’s first term to strengthen the petroleum resources rent tax, it is projected to raise only $1.7 billion per annum over the next four years, which is just $57 million (or 3½%) more than it did on average over the 10 years to 2008-09, even though Australia’s LNG exports are now running at more than $65 billion per annum, compared with just $4 billion per annum in the 10 years to 2008-09.

And, as I suggested here earlier this month, serious consideration should be given to reintroducing a federal inheritance tax, given estimates that almost $5½ trillion is likely to be transferred from baby-boomers to their 50- and 60-something offspring over the next two or three decades. But that may well require more “political capital” than the government is willing to risk.

Finally, the states and territories should be part of any serious conversation about tax reform. They impose one of the most inefficient and economically burdensome stamp duties in the armoury of Australian governments, which could and should be replaced by a broadly-based land tax that includes the “family home”, accompanied by transitional provisions to prevent “double taxation” of recent property purchasers. But it’s not just about efficiency. As David Thodey cogently argued in the Review of federal financial relations which he undertook for the former NSW Government in 2021, there is something fundamentally unfair about a system of property taxation which requires people who, for whatever reason, move home several times during their lifetime to contribute more to the cost of providing schools, hospitals and police services than someone who lives in the same home for their entire adult life.

The federal government could encourage the states and territories to pursue this reform by assisting them with the cost of managing the transition – which it should do, given that federal revenues are likely to be boosted by the broader impact of more efficient land use which this reform would generate. But if the states aren’t prepared to do that, the federal government could alternatively reintroduce the land tax which previous federal governments maintained between 1910 and 1954, and give the revenue to the states on the condition that they abolished their stamp duties.

The states and territories should also be encouraged to abolish or substantially reduce the tax-free thresholds in their payroll tax systems, which result in the foregoing of substantial amounts of revenue ($3.9 billion in NSW in 2024-25, or 30% of the revenue actually collected, $2 billion in Victoria). There is absolutely no evidence to support the widely-held view that payroll tax exemptions for small business do anything to boost employment: on the contrary, research by the e61 Institute suggests that these concessions are detrimental to employment growth, by encouraging small businesses to limit their employment to just below the threshold at which they become liable to pay payroll tax.

More broadly, payroll tax is actually very similar to the GST in its operation and incidence. GST taxes the difference between sales revenue and cost of goods sold (which is why it is called a “value-added tax” in Europe, where it was first conceived).

But as a moment’s thought will confirm, the difference between sales revenue and cost of goods sold is, for most businesses, wages and salaries (plus labour on-costs) plus sales and marketing expenses and what the national accounts call “gross operating surplus”. So the only practical differences between GST — which is widely considered a “good tax” — and payroll tax — which is routinely derided as a ‘tax on jobs’ and therefore a “bad tax” — are that the GST taxes the gross operating surplus as well as wages and salaries, and the GST doesn’t tax exports.

Moreover, most other “advanced” economies levy much higher payroll taxes than Australia does — they just call them “social security contributions” or “social insurance taxes” rather than “payroll tax” — without resulting in higher unemployment than in Australia.

Tax reform isn’t a “magic bullet” that can solve all of the economic and other challenges which confront Australia. But it can make an important contribution to addressing many of them. The prime minister and the treasurer have indicated they’re willing to spend some of the enormous amount of political capital which they now have in the aftermath of last month’s election. That’s very encouraging. It’s up to others to help ensure, by approaching forthcoming conversations about tax reform with open minds and vested interests left behind, that that political capital is spent in the most effective way.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.

Readers might be interested to read Part 1 of this article from Saul Eslake