OK Boomers not so okay

June 30, 2025

I was born in 1954, a year after the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. That makes me 71. It also makes me a baby Boomer, part of an ageing population, that, like Charles and Camilla, is increasingly seen as both irrelevant and privileged. Not to mention a burden on the public purse.

Politicians and economists, talk, ad nauseam, about my generation as a problem to be managed. Grave pronouncements about the ballooning cost of Boomers who didn’t, as predicted, die before they got old, are accompanied by images of the aged in varying states of decrepitude, wheeling frames or wandering confused, a veritable tsunami of people whose longevity, rather than celebrated, is something to be feared. Perhaps resented.

Boomers timed their arrival well, born between 1946 and 1964, a time of booming growth, kids, who, like me, left school before completing Year 12, had no trouble getting a full-time job. And while there was no maternity leave or equal pay, sick leave and holiday pay were always part of the package.

Unions were a force then, with strong membership and leaders who fought for workers’ wages and conditions, they mostly had your back. Male backs in particular, it has to be said. Today, not so much. Dwindling to dwindled membership and union bosses too willing to bargain away hard-won conditions for meagre pay rises, unions are part of the problem.

Even working in fairly menial jobs, without much of an education and little in the way of skills — though I did smash out a mean 100-words a minute on my Facit — I had far better conditions than many highly-educated young people leaving university today.

Boomers scraped into adulthood before free-market ideology swept the world. In Australia, we were quick off the mark, so-called lefties, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, implementing neo-liberal policies with zeal: free (that is, taxpayer-funded) university soon becoming roadkill.

And that was just the beginning, the benefits Boomers took for granted, eroded by privatisation and deregulation — think utilities — and a radically depleted welfare net – think JobSeeker, its fortnightly payment now well below the poverty line.

In spite of the indulged and privileged stereotype, most Boomers do not live in swanky homes in filmic locations planning their next cruise while quaffing expensive booze.

Research shows that one in six baby Boomers don’t own their own home, and approximately two-thirds of Australians over 65 don’t have enough money or savings to retire comfortably, instead, relying on the government pension for their main income.

The chance of anyone, especially an over 55-anyone, finding a job with tenure and sick leave and holiday pay, is about as likely as Trump changing his mind on global warming. It’s a catch-22 that forces not-so-cashed-up Boomers to eat into the little savings and super they have amassed. For those who don’t own their own home, the future is even more dire.

No more dire, though, than for women who, while no one was looking, have become the fastest growing group of homeless in Australia. The combination of interrupted work, unequal pay, part-time hours in often poorly-paid jobs in order to prioritise the needs of family, has also contributed to making women financially vulnerable in older age.

In spite of the warring between Boomers and Millennials, it still stands that if you are born into wealth, you will do well. Those who had it all, still do, a tiny proportion of the population who were for the most part, as they are in every generation, already privileged, the opportunities that go with that privilege, handed down between generations, paving streets with gold for the lucky few.

Internships are a contemporary example of what inter-generational privilege looks like. Those who can afford to take up a full-time internship must either be independently wealthy or, the most likely scenario, have parents who can financially support them for the year or years of their internship. The bank of Mum and Dad is another. And let’s not forget nepo babies!

Not withstanding ageist rhetoric, most Boomers do give back. Many Millennials depend on their parents for free childcare, Boomers are often caring for elderly parents, and they make up the larger number of volunteers.

They are also joining younger generations in protests against global warming. Unconstrained by the nine-to-five and with a debt to repay for the damage done, expect to see more grey plumage among climate-change protesters.

Boomers must also accept some responsibility for the legacy handed on: self-interest cultivated by an economic madness that enriches the wealthy — those who must have had a go — and punishes everyone else – those who obviously didn’t.

If we are to understand and confront the shrinking opportunities of Millennials, we’d do far better to examine issues of class and the neo-liberal policies of subsequent governments.

Instead of stereotyping and pitting generations against one another, we could be working together to change structures that deny younger generations economic rights.

Much of what Boomers have today is thanks to Gough Whitlam, Australian prime minister from 1972-75, who in a very short time did lots of good stuff including the gift of free education.

While it was a gift that changed many Boomers’ lives, it’s worth noting that in 1975, a year after free education was made available to the masses, only 8.6% of the population had taken up what turned out to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Inconceivable, if you don’t factor in class.

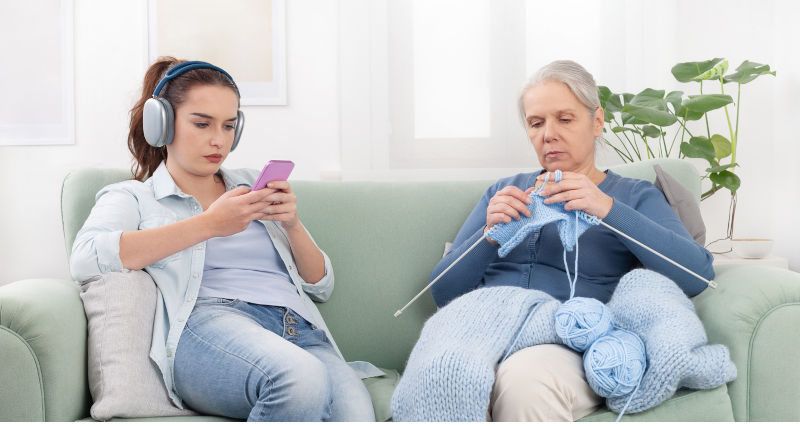

Boomers’ so-called privilege is not the only reason we are scorned. In a youth-obsessed and death-denying culture, the reality of ageing is something to be ashamed of and fought against.

Ageist attitudes are particularly cruel to women, our value tied to youthful beauty and fertility, a continuum that infantilises, dismisses and excludes.

And although flooded with images of the infirm whenever old age is discussed, most people do not end up in nursing homes, ABS figures showing that only 4.1% of older Australians, defined as those 65 and over, were living in cared-accommodation.

Ageism is why we are so often surprised when someone in their eighties or nineties is mentally alert, sociable, active and independent. So ingrained are the stereotypes of old age, we don’t realise that robust older age is actually the norm.

It stings being the subject of ridicule and derision but that is how the ok Boomer narrative has framed an entire generation, our past and ongoing contribution almost completely overlooked, when, for the most part, we have worked long and hard, and lived simple honourable lives.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.