Environment: Forget 1.5 degrees C, even 2 degrees C, while forests and peat disappear and natural gas booms

July 20, 2025

Peatlands are vital for human survival, but we are destroying the few that are left. Australia’s gas industry facing a volatile future. Chinese banks funding the destruction of tropical forests – not good for humans or tigers.

Peatlands: vital but unprotected

There are 4 million km2 of peatlands around the world – 3% of the land surface area. Boreal peatlands are by far the most extensive – Russia and Canada alone contain almost two-thirds of total peatland. Just over a quarter of global peatlands are within Indigenous people’s lands.

Peatlands store 600 gigatons of carbon, more than is stored by all the world’s forests. They are also critical water reservoirs, storing 10% of the world’s nonglacial freshwater, and play a vital role in water regulation, buffering the effects of floods and droughts by capturing rain quickly and releasing the water gradually. Peatlands provide habitat for many species of animals and plants. They help control regional air temperatures, are sources of food and fibre and have enormous cultural and recreational value.

Regrettably, large areas of peatland have been subject to cutting for fuel and horticulture and have been drained and degraded for agriculture, forestry, mining, roads and other infrastructure. Warmer temperatures and drier conditions are now leading to thawing of permafrost and wildfires. Almost 90% of remaining peatlands are currently under high human pressure.

You might think, bearing in mind the losses that peatlands have already suffered and the importance of peatlands for environmental and human health, that peatlands would be well protected now. You’d be wrong. Only 17% of global peatlands are within protected areas, of which almost half fall within the “non-strict/multiple use” protection category – hardly any protection at all. “Strictly protected” areas cover only 8% of boreal and tropical peatlands, while temperate peatlands do little better at 16%.

Australia has just over 21,000 km2 of peatlands (equivalent to a third of Tasmania), of which just over a third is in a “strictly protected” peatland area.

There’s nothing surprising about what needs to be done: better data and monitoring systems; support for Indigenous-led stewardship, conservation and protection; and improved co-ordination of the action plans of intergovernmental bodies tackling climate change and loss of biodiversity.

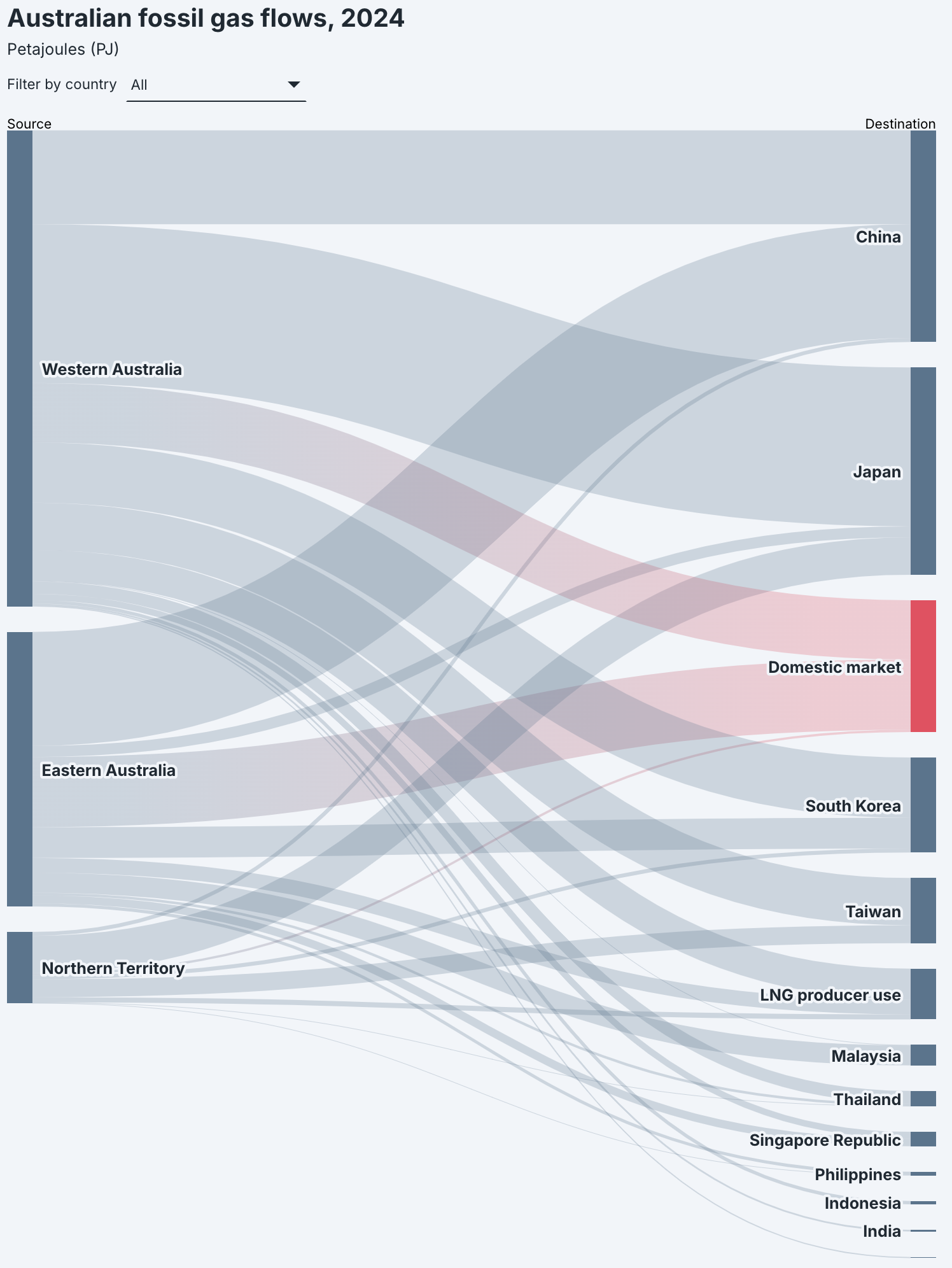

Australia’s natural gas production and destination

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has produced a detailed report on Australia’s natural gas production, domestic use and export as liquefied natural gas. As the figure below demonstrates, in 2024 the majority of Australia’s gas was produced in WA (58%) and an enormous proportion (84%) was exported, with a third of the exported gas going to each of China and Japan.

But while the industry and governments across Australia continue to view natural gas as the gift that keeps giving (to whom is a good question), some weeds are beginning to appear in the vaporific Elysian Fields.

Weakening Demand, creeps slowly around the host and eventually throttles it. In 2008, Australia exported 15 million tonnes (Mt) of LNG. This grew by an average of 5Mt per year over the next 12 years to 77Mt in 2019. Since then, however, export growth has slowed to about 1Mt per year to 81MT in 2024.

Increasing Supply, a rapidly spreading invasive species from the US and Middle East. The global LNG market is facing a glut over the next five years. Liquefaction capacity is projected to increase by 31 billion cubic metres during 2025 and by 2030 this would have cumulatively reached 284 billion cubic metres. Most of the increased capacity will be in the US (50%) and Qatar (23%); Australia will contribute about 2.5%. The increasing supply is pushing LNG prices down.

Yet the authorities tell us that there’s a looming shortage of gas for Australia’s domestic use because of decreasing supply on the eastern seaboard and increasing demand in the west. But as others have commented, “Australia doesn’t have a gas supply shortage. We have a gas export problem”.

There’s lots more in the IEEFA report for the aficionados amongst you.

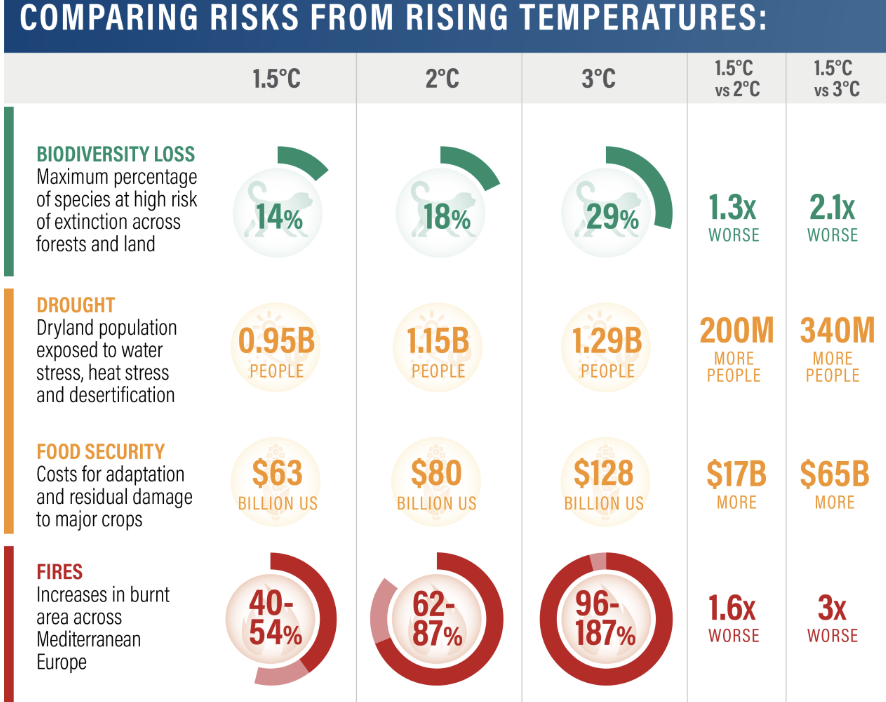

Understanding the 1.5oC goal

Where did the idea to limit global warming to 1.5oC come from? Is it still possible to keep warming under 1.5oC? Or has the Earth already warmed more than 1.5 degrees? What if we already have or soon will exceed 1.5 – what should we do then? What difference will it make if we keep warming under 1.5 rather with 2oC? (See the table below for a few examples.)

If you want to learn a bit more about the goal of keeping global warming under 1.5oC, I strongly recommend the summary from the World Resources Institute. For anyone who wants even more detail, Climate Analytics has published a 30-page brief about the latest science regarding 1.5.

Chinese banks funding the destruction of tropical forests

A country as large, in numerous ways, and developing as rapidly as China is bound to have some internal contradictions – e.g., leading the world in both annual greenhouse gas emissions and making the biggest efforts to decarbonise their economy; responsible for 50% of the world’s consumption of coal and also the world’s major producer of technology for the green economy.

So we shouldn’t be too surprised to learn that in 2021, China signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use which committed them to stop deforestation and realign financial flows accordingly but still funds forest loss in 2025.

China has the world’s largest banks, but has no policies that restrict imports of goods linked to illegal deforestation or to prevent finance flowing to companies with ties to illegal deforestation.

China is also the world’s largest international funder of companies that trade in deforested goods. Between 2018 and 2024, Chines banks provided US$23 billion to businesses producing “soft commodities” such as timber, pulp, paper, beef, soy and palm oil, all of which are associated with deforestation, much of it illegal. I doubt it is any coincidence that China is also the world’s largest importer of soft commodities.

It is also worth remembering that deforestation, illegal and state-sanctioned, not only damages the environment but is also often associated with abuses of land and human rights.

Just to make one point clear, Brazilian and Indonesian banks provide more money than China to activities that are associated with goods linked to deforestation but they mainly fund logging within their own countries.

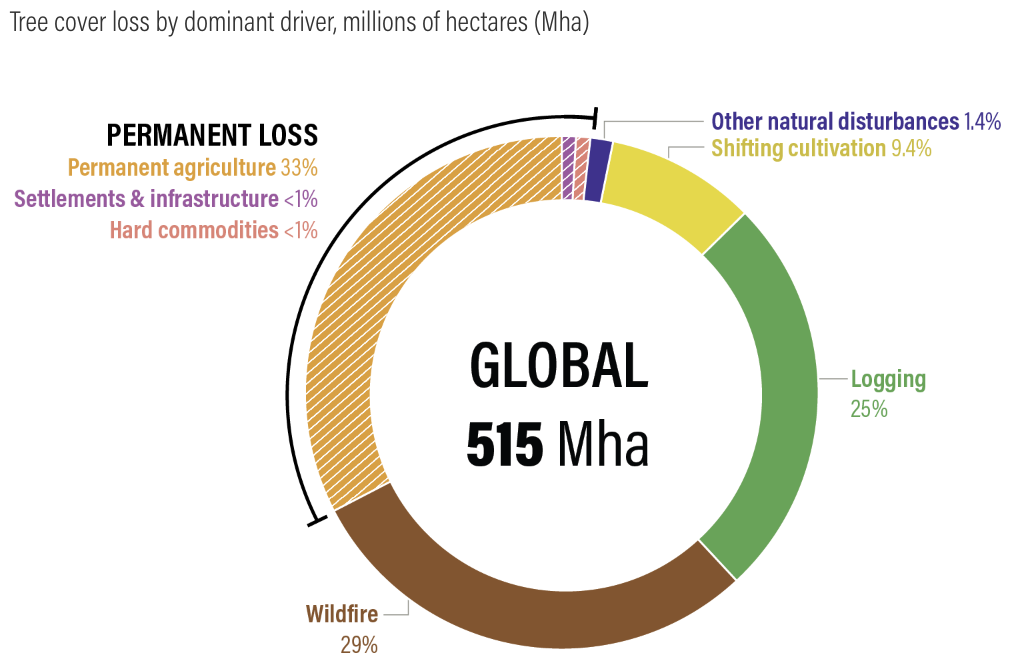

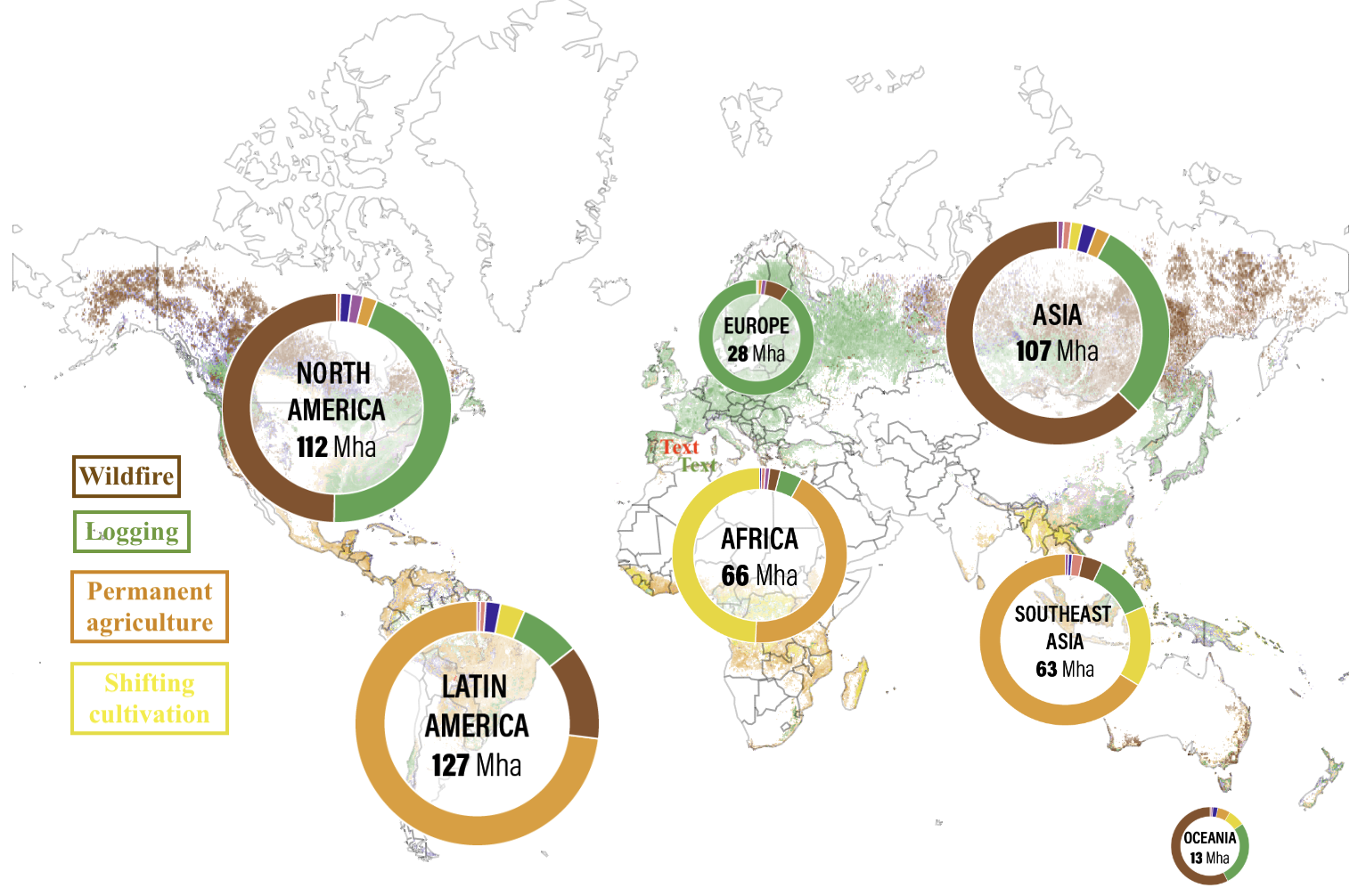

Forest loss varies by cause and consequence across the world

During 2001 to 2024, 515 million hectares (Mha) of tree cover was lost worldwide. This equates to the whole of Australia except for WA. One-third of the loss was caused by permanent land use change (the trees won’t grow back) but in tropical primary forests the figure was 61%. Although the other two-thirds of the loss is classified as temporary, the time taken for forests to regrow after, say, a fire or logging may be decades to hundreds of years and the condition of regenerated forests is often poor.

Across the regions of the world, the causes of the loss vary greatly, as shown in the map below.

For instance, while infrastructure for activities such as illegal and legal mining and oil and gas production cause less than 1% of tree cover loss globally, gold mining in Peru is a significant problem. In tropical Africa, shifting cultivation causes almost half of the tree cover loss, but this is a form of subsistence farming that local communities have practised for many years, typically allowing time for soil and vegetation to recover after a period of cultivation.

Clearly, if the causes of loss of tree cover differ from place to place, strategies to tackle the ongoing loss need to vary accordingly, although cutting off funding and reducing demand in wealthy countries for goods originating on deforested land are common features.

When humans meet tigers, it seldom ends well for either

“Logging and palm oil plantations are expanding in Malaysia. That’s depriving wildlife of habitat and driving the critically endangered Malayan tiger and populations of Native peoples closer together. As the number of tiger attacks on people increases, a new Indigenous anti-poaching team is combining traditional knowledge and high-tech methods. Can they reduce the number of deaths among both humans and the big cats?”

So begins a multi-faceted story, accompanied by great photographs, that illustrates a situation that is increasingly common in developing nations where humans and wildlife are being forced into closer and closer contact.

Logging in Malaysia deprives wildlife of habitat

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.