Labor’s Left majority: A defining moment

July 1, 2025

The May 2025 election delivered something quietly historic. For the first time since the 1970s, the Labor Left faction holds a majority in caucus.

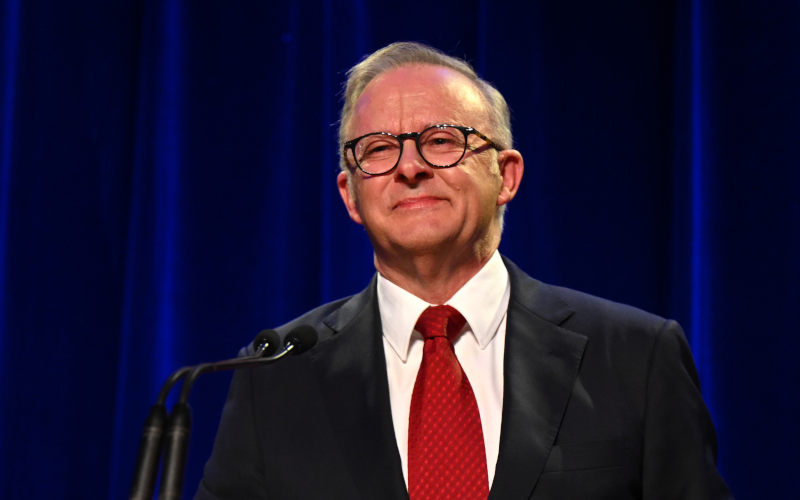

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, a life member of the Left, now leads a government where his faction controls the numbers. Yet despite this apparent triumph, there is little sense of rupture, and even less of radicalism.

What should be a generational opening instead feels like the management of a new constraint: how to hold power without the capacity, imagination or courage to use it.

Labor’s internal culture, like its parliamentary logic, remains deeply conservative – even when led by the Left. Caution, compromise, and consensus are hard-wired.

It is the latest chapter in a much longer story: the erosion of Labor’s radical tradition, the shrinking of its narrative ambition, and the tightening grip of the consent ecology – the set of social, media, economic, and institutional expectations that discipline what any government dares to do.

From authentic radicalism to risk-averse centrism

Australia’s Labor tradition was never revolutionary. But it was, for much of the 20th century, authentically radical. It shared with other social democratic parties the idea of redistribution, progressive taxation, an expanded role for the public sector, public equity and in some cases even nationalisation.

In Australia, Labor built Medicare, expanded public housing, created a national superannuation system, and for a time pursued nationalisation, income redistribution, and regional independence in foreign policy. It was a party with a base, not just voters.

But from the 1980s onward — amid financial deregulation, party professionalisation and the globalisation of the policy imagination — Labor entered a long, bumpy drift to a form of centrism that increasingly failed to inspire electorally and failed to deliver structurally. The higher the stakes got — from climate to housing to inequality — the narrower the party’s policy scope and action became.

Caucus discipline, once a mechanism for collective power, became a tool of ideological containment. The sharp edges of debate were filed down. Rebels were marginalised or exiled. The gap between the scale of change required and the policies actually pursued widened into a chasm.

What a Left-majority caucus could mean

The May 2025 result offers a potential break in this pattern – but only if the Left understands its role not simply as stewards of government, but as challengers of consensus.

Among new MPs and Senators are nurses, union organisers, housing campaigners and mental health professionals. Many are aligned with the so-called “Old Guard” of the Left. But they enter a system that dulls boldness and prioritises message discipline. The ecology of consent— made up of fiscal orthodoxies, media gatekeepers, institutional inertia and geopolitical deference — remains largely intact.

To use this moment, Labor’s Left must do more than quietly plead for better policy within Cabinet. It must reshape the narrative terrain, reanimate public ambition, and restore a sense of collective agency to the electorate. That means:

- Telling a bigger story about how we got here and where we’re going;

- Rebuilding public support for structural solutions, not just too little, too late adjustments;

- Challenging inherited assumptions – such as the need for endless growth, or that Australia can thrive as a low-tax nation, or that housing is a market good before it is a human right; and

- Above all, normalising the idea of transformation internally in in Australia’s location and role in the world economic and political system.

The risk of governing as managers of decline

If Labor continues on its current trajectory — delivering incremental relief while leaving the structures of inequality intact — it risks governing not as a party of change, but as a manager of decline. This is how parties with historic missions become hollowed out.

The Left, for all its numbers, will find that without a strategy of public mobilisation, it cannot escape the trap of timidity. Numbers only shift things when used for change.

Legacy or lost opportunity?

Albanese’s personal story has long symbolised Labor’s roots. Now, with caucus at his back and the Right numerically outnumbered, he faces a choice that is both personal and political: stabilise the centre, or redefine it over a second, third or even fourth term.

The ALP Left has been given a rare institutional alignment. If it fails to use it to make change, it will mark not a moment of revival, but the closing of a final door. And that would confirm that the era of authentic Labor radicalism has truly ended.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations..