No simple solutions for specialist problems

July 21, 2025

A referral to a specialist doctor should set patients on a smooth path to the care they need. But it can be more like an alpine hike, with steep fees and treacherously long waiting lists. It’s putting lives at risk.

One man in rural NSW said he had to wait six months after a prostate cancer diagnosis before he could see a specialist, then two more months before his surgery. In the meantime, the cancer spread, requiring more invasive surgery and increasing the risk the cancer will return.

Our recent report on specialist care proposed a range of solutions: better workforce planning, unblocking the training pipeline, expanding public clinics in areas with too little care, and cracking down on extreme fees.

There are problems across the whole system, so no single measure can stop a million Australians each year from missing out on care. And solutions will fail if they ignore the underlying problems of weak competition and missing policy guardrails.

Some doctors have argued that the government should simply pay them more. They say Medicare indexation isn’t covering their cost increases, forcing them to lift fees.

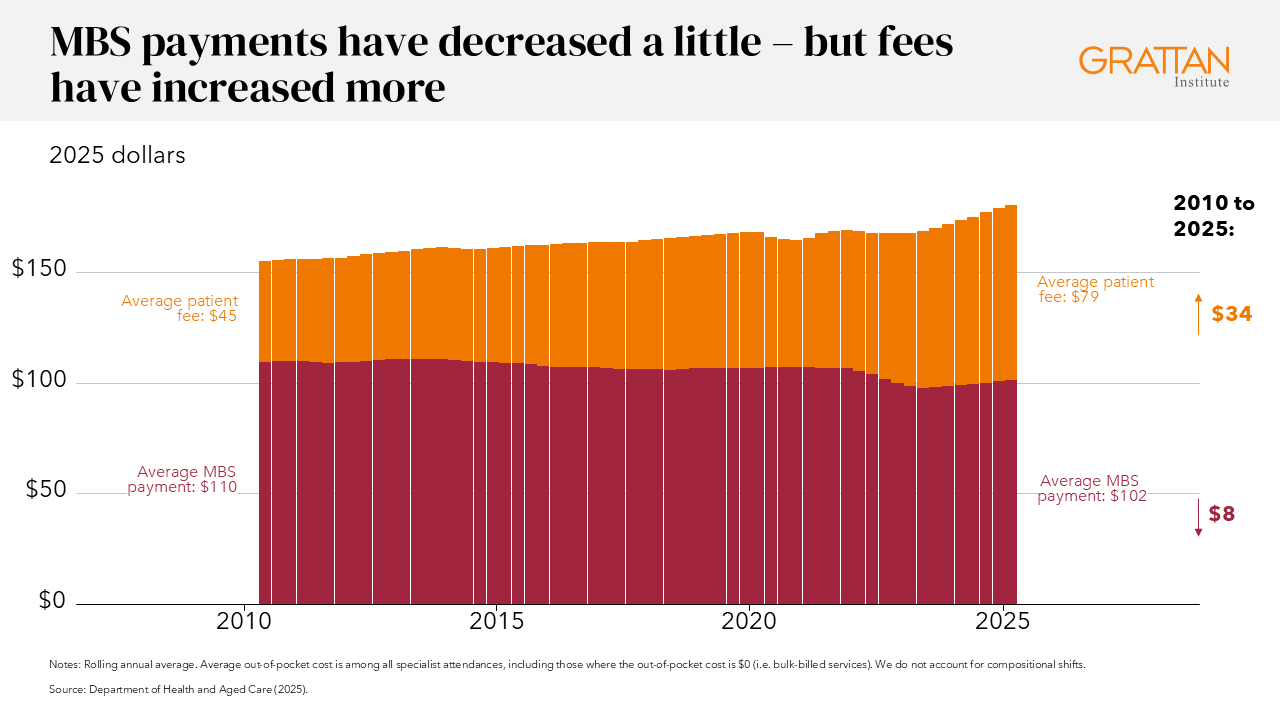

Medicare payments have slightly trailed inflation, which closely tracks average specialist clinic costs. But Medicare shortfalls can’t explain the size of the fee increases. Between 2010 and 2025, on average, specialists charged patients an extra $4 for every $1 in lost Medicare funding.

For example, between 2018 and 2023, the average Medicare benefit for an initial consultation (item 104) decreased by $4 in real terms, but doctors charged patients $29 more. For an initial psychiatry consultation (item 296), real Medicare rebates decreased $13 – but average patient out-of-pockets increased by $108.

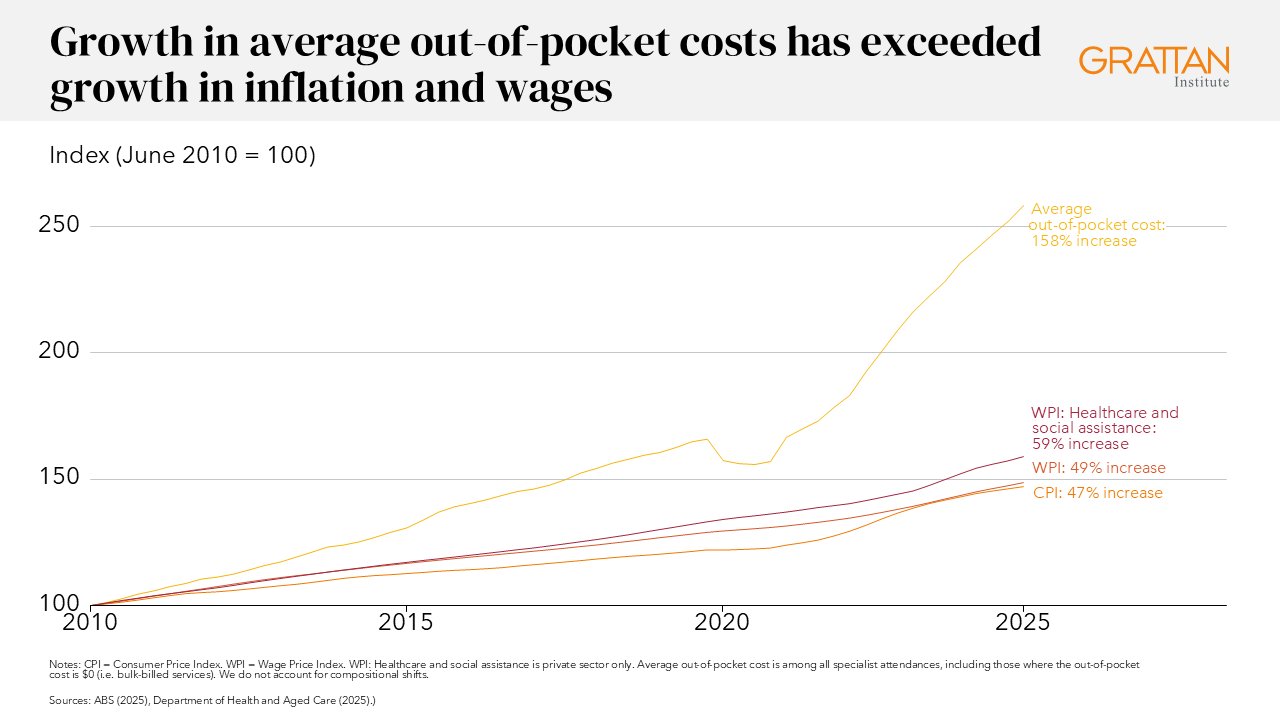

Overall, growth in out-of-pocket costs for specialist appointments has far exceeded growth in wages or consumer price inflation.

There’s no evidence of shrinking profits. From 2006 to 2021, the cost of running clinics rose only 2% a year, while profits rose by about 5% a year. Specialist businesses are more profitable than almost any other industry, and medical specialties are 9 out of 10 of the highest-earning occupations in the country.

These are average incomes: some earn much more. We only recommend government action to curb the most extreme fees, where specialists charge on average more than three times schedule fee. That would affect just 4% of specialists.

Those extreme fees clearly aren’t due to problems with government funding – the vast majority of specialists charge much less and still turn a healthy profit.

Falling government funding isn’t the main problem, and a blanket rebate hike isn’t a good solution. It could cost billions, and there’s no guarantee that it will flow through to lower fees. After previous MBS Safety Net and GP rebate changes, doctors held onto much of the new funding.

Still, Medicare payments may be too low for some services. It’s hard to know because most payments haven’t been reviewed for decades. Instead of ad hoc indexation freezes, squeezes, or splurges, we recommend the federal government review the cost of providing care to ensure Medicare payments are appropriate.

Another proposal is to publish more information to help patients shop around. Graeme Samuel called for a national database showing every specialist’s fees and outcomes, on the theory that transparency will force down prices. Transparency is good, but it’s no substitute for bolder reform.

People should have information about the cost and quality of care. But even for products that are easy to compare, comparison websites are no panacea. One state government has had to pay consumers to use their energy price comparison tools. And the FuelWatch website has done little to save consumers money.

Comparing specialists is much harder. The government will soon publish cost data on the Medical Costs Finder website. But measuring specialist quality fairly — especially for non-procedural care — is difficult. Publishing complication rates for surgery is one thing, but how do you risk adjust a psychiatrist’s caseload?

Even if the right data could be collected and published, and if patients used it, in many cases patients aren’t choosing between several private specialists. It’s often a choice between the one available and a long wait for care at the public hospital. Information helps only when there are genuine alternatives.

Specialist medicine isn’t a well-planned system or a functioning market. That’s why boosting funding and shining a light on quality won’t be enough. That won’t fix the restricted and uneven supply of specialists, or the holes in the safety net that leave many communities without enough public services.

Instead, it’s time to confront the deeper policy failures that are harming patients. That means tackling planning, training, funding and fees. Some of those changes might be politically challenging. But with fees rising fast, and wait times unacceptably long, not solving the root problems will ultimately cause a bigger backlash.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.