Spiritual malpractice: The Vatican's dodgy saint-making business

July 6, 2025

Pope Leo rubberstamps the controversial canonisation of a multimillionaire Italian’s adolescent son.

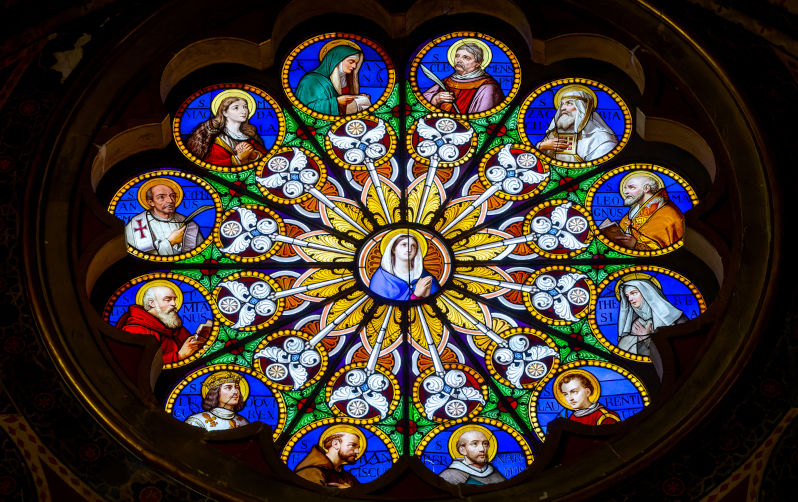

The families of my two grandmothers (both paternal and maternal) have been Roman Catholics, I don’t know, probably since God was a boy. And since I attended a parochial school in a traditional ethnic neighbourhood, I grew up with the “old-fashioned” devotions – the rosary, May crowning and benediction on First Fridays. Of course, statues and pictures of the saints, including holy cards, were also a regular part of my Catholic childhood and adolescence.

Honouring the saints and viewing them as models of holiness — especially the martyrs — is integral to our Catholic faith. This has been true since the very beginning of Christianity. We also profess in our most ancient credal statements that we believe in “the communion of saints”.

However, it wasn’t until the 1990s, while I was working at Vatican Radio, that I became more curious about the process of officially naming someone a saint. Just a few years earlier (in 1983 to be precise), Pope John Paul II had radically changed a process that had evolved over centuries to fast-track the beatification and canonisation of many more individuals.

There used to be a 50-year waiting period from the time of a candidate’s death before the process could even begin. However, the Polish pope drastically reduced that to just 10 years (and later a mere five!). He also eliminated the number of miracles required, the necessity for a “devil’s advocate”, and other protocols that complicated the process. He and his aides claimed that the intention was to help expedite the inclusion of more laypeople among those “raised to the glory of the altars”.

But the first person to benefit from the rule change was a Spanish priest named Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the founder of the secretive and controversial group called Opus Dei. John Paul beatified him in 1992, just 17 years after the prelate’s death. He then canonised Escrivá in 2002. This was done in what was considered, at the time, record speed. Others, such as Mother Teresa of Calcutta and even John Paul himself (“Santo Subito”), have since been canonised even more quickly.

On the day Pope Francis passed away, 21 April, the Holy See Press Office announced that a high-profile canonisation set for the following Sunday, 27 April, had been suspended. The future saint in question was Carlo Acutis, an Italian who was just 15 years old when he died of leukemia in 2006.

Although it would have been unusual, the new pope could have chosen not to proceed with the canonisation, which has some extremely problematic aspects associated with it. Instead, on 13 May, during the first ordinary public consistory of his fledgling pontificate, Leo reaffirmed his predecessor’s decision to canonise the adolescent. He set 7 September as the date for the ceremony.

The Archdiocese of Milan opened Acutis’ cause for canonisation in the autumn of 2013. This initial process lasted about three years. In 2018, Pope Francis declared the boy “venerable”, meaning he is worthy of veneration or imitation. He ordered that Acutis be beatified in October 2020. The ceremony took place in the Italian hilltop town of Assisi, the home of the beloved saint whose name the late pope took as his own.

Bankrolling canonisation of her son

Acutis’ mother, Antonia, was the driving force behind the effort to have her son made a saint. She and her husband, Andrea, both from important and extremely wealthy northern Italian families, have an estimated net worth of US$10 million, according to some sources.

The boy’s grandfather and the family’s patriarch, also named Carlo Acutis, oversees an estimated fortune of about US$1.5 billion, primarily accumulated over several decades in the insurance and real estate sectors.

Reputed to possess one of the largest private collections of Renaissance art in the world, the Acutises have generously utilised their resources for philanthropic endeavours. For instance, they operate a special foundation that promotes education and scientific research. They also contribute to art restoration and finance hospitals and clinics to enhance health services.

But why does this son of multimillionaires deserve to be officially declared a saint? What makes him so unusual among other adolescents? His mother and others who have backed his cause are promoting him as a patron of responsible use of social media and the internet. The youngster created a website that promoted Eucharistic adoration and shrines around the world that celebrate it. He seemed like a normal kid, one of those “saints next door”, as Pope Francis would say.

Evidently, his peers in school also thought he was quite common, so common that they had no idea he had any religious inclinations beyond those of a typical Catholic kid growing up in Italy.

And that is something, in fact, to applaud and celebrate. However, there is something troubling about the devotion (or “cult”, as they say in Vatican speak) that his mother and others have helped create around him. It’s not about the enormous sums of money they may or may not have spent to achieve their goal.

Rather, it is primarily about his clothed adolescent body, which is displayed in a glass case in a church in Assisi.

At first blush, this spectacle appears to be another example of Mediterranean popular religiosity and its fascination with relics and the dead bodies of saints, which are routinely paraded from town to town and even around the world. But in fact, it’s something far more disturbing.

‘Another grotesque case of Catholic child abuse’

A top-notch international human rights lawyer, who is a serious practising Catholic, pointed something out that —to my shame — I missed completely. “I am suitably scandalised,” he said. “When my wife and I went into the church, I was horrified to find the body of a kid. Nuns were kneeling there praying and, after a while, groups of school kids came through. I didn’t know anything about Carlo’s story at that stage but I was horrified at the kid in the glass case, lying there, dead. The text by the glass case told the story about how, after he died, the body had been dug up and brought there in solemn procession," he continued.

“What this is all about, and what has haunted me ever since, is that this is yet another grotesque case of Catholic child abuse, but this time put on public display. Carlo was no doubt a nice kid. His death was certainly tragic. But now he was being exploited by the Catholic hierarchy of Assisi and elsewhere for their own gratuitous purposes. Exploited to promote their relevance to young people. Exploited to ensnare more kids," the human rights lawyer said.

“Exhumed and clothed and cased and abused. This, to me, is worse than the sexual abuse of an individual child by an individual priest because it is institutional. It is gross institutional, ecclesiastical child abuse. No-one cares about the poor kid. It’s all about what his child-like body can be used for. It is gross and grotesque and abhorrent.”

And evidently, most Catholics — including our dear Pope Leo — can’t even see this.

That’s how clueless and complicit we all are in this still-unfolding abuse scandal that seems to be without an end.

Naturally, everyone wants to see their favourite Catholic heroes receive the Church’s official seal of approval and be declared saints. The founders of religious orders, modern-day martyrs, and champions of various issues concerning justice and peace… the list goes on.

However, despite the possibility of jumpstarting the process, as John Paul made possible, there are still many canonical and bureaucratic hoops to be navigated. This takes time and money. And it doesn’t hurt if you know the right people to help that along.

Although it is strenuously denied by Vatican officials and others who are involved in the saint-making business (such as trustworthy physicians who attest to miracles, theologians who judge the orthodoxy of a candidate’s writings, and canonists who do what canonists always do – make sure everything is followed to the letter of the law), there’s a lot of politics involved as well.

And if you think this is all the fault of the late Papa Wojtyla, you’d better think again. He may have gotten the ball rolling, but his successors — every single one of them — have accelerated the momentum. Pope Francis tops the list. The 942 people he canonised during his 12 years in office (many of them in groups of martyrs) are nearly twice as many as those John Paul II made saints in his more than 26 years as pope.

The reigning pope has the final say

Clearly, many of the people Francis canonised (and the 45 that Benedict declared saints during his brief time as Bishop of Rome) came from the 1344 individuals that John Paul beatified.

However, Benedict XVI added another 870 future saints (beati) to the pipeline, while Francis added a remarkable 1541. Ultimately, though, it is the reigning pope who must approve any beatifications or canonisations that occur during his pontificate. This is where Pope Leo enters the picture.

Republished from UCA news, 20 June 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.