The geopolitical context of Albanese's China visit

July 18, 2025

Prime Minister Albanese and I have a few things in common. We were both born on 2 March and we have both been in car accidents, and as I write this, we are both in the People’s Republic of China.

Of course, Albanese’s reasons for being in China are far more important than my own. While I am living out my childhood dream of practising kung fu in China, Albanese is continuing his government’s job of mending our most important economic relationship.

China is Australia’s largest trading partner. We hear this phrase repeated often; it is common knowledge. But even this statement obscures the sheer scale of Australia’s economic dependency on China. In 2023-24, China alone accounted for 26% of Australia’s international trade.

It is spurious to suggest that in the event of conflict, Australia could reroute this much trade. The health of our economy hinges in large part on China’s continued appetite for our beef, barley and iron ore. Not to mention Chinese international students and tourists, who effectively subsidise Australia’s higher education system by paying exorbitant fees.

Kudos, then, to the Albanese Government for restoring a semblance of health to our relationship with China. Under the previous government, Australia-China relations were in deep freeze. There had been no direct ministerial-level contact for several years, and China had slapped tariffs and import bans on several Australian products. Australian wine, for example, was hit with tariffs as high as 218.4%, causing the value of wine exports to China to collapse from $1.24 billion to $1 million.

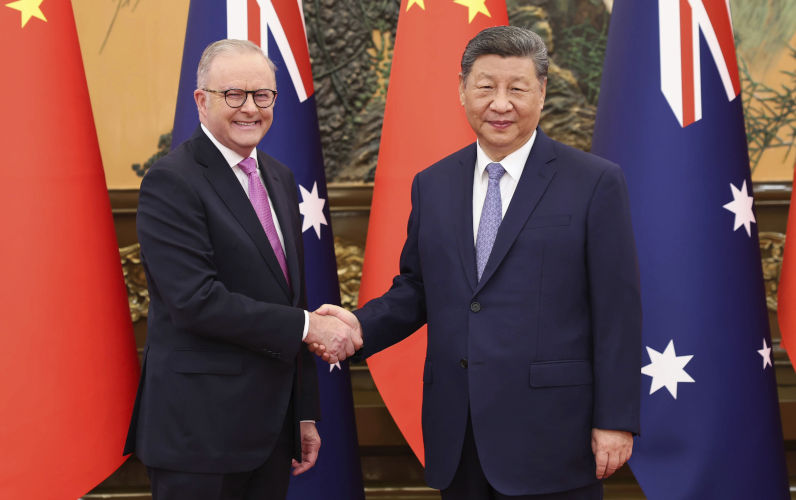

These tariffs are now gone, and Albanese recently visited China for the second time as prime minister, and met Chinese President Xi Jinping for the fourth time.

This progress is undeniably real. But even the most optimistic commentary on the potential for further economic co-operation between Australia and China cannot hide the fact that the relationship operates underneath a gloomy strategic cloud.

Even when the US is governed by a normal person, Australia must navigate the pitfalls of having its largest trading partner (China) and its primary security ally (the US) engaged in strategic competition. As with everything, Trump rachets this tension up to eleven, by neglecting diplomatic norms and showing little regard for the international consequences of his actions.

However, I will say this one positive about Trump: his tendency to say the quiet part out loud is forcing Australia to finally have some long overdue and serious conversations about our relationship with the United States.

AUKUS is the most pertinent example of this. A trilateral agreement between Australia, the UK and the US, the primary aim of AUKUS is to supply Australia with nuclear-powered submarines. The deal was originally signed and passed through Congress during the Biden administration.

The Trump administration recently announced a review into AUKUS, to ensure that it coheres with the so-called “America First” agenda. Their concern (admittedly a very legitimate one) is that the US will be unable to build enough submarines to supply Australia with the Virginia-class vessels that we were promised. The worry is that providing nuclear submarines to Australia could come at the expense of supplying them to the US Navy.

To get around this potential problem, US Undersecretary of Defence Elbridge Colby has reportedly suggested that Australia give “pre-commitments”, either publicly or in private, that Australia’s nuclear submarines will be used against China in any conflict with the US over Taiwan.

It is worth pointing out that such a commitment would go beyond the text of the ANZUS Treaty (the founding text of the alliance), which commits Australia and the US only to “consult” one another in the event of conflict.

Indeed, would any self-respecting country give up its sovereign right to decide on the most important question any government can face, that of going to war? Australians have every right to be offended even by the suggestion that we would do this.

Australia has also repeatedly rebuffed US suggestions that we increase our defence spending.

Given this undercurrent of tension in the Australia-US relationship, compounded by the fact that Albanese has yet to secure a meeting with Trump, Albanese’s meeting with Xi takes on even greater significance.

Some within China have long viewed Australia as potentially the “weakest link” in the US chain of alliances accross Asia. By applying economic pressure and diplomatic seduction, it is hoped that Beijing can wean Australia off its strategic dependency on the US.

Australia is well-placed to become a “geopolitical swing state”, aligning wholeheartedly neither with China nor the United States, but rather using its strategic position to pursue an independent foreign policy and extract concessions from either side.

Will this happen? I have my doubts. Foreign policy is as much about values and identity as it is about economics and security. It is difficult to imagine Australia standing back in the event of conflict between the US and China.

Nonetheless, Xi’s warm welcome of Albanese, and boringly predictable press conference, is designed to remind Australia (and the world) that they have choices. The US is no longer the only superpower on the block.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.