Time for Australia to look beyond China and the US

July 22, 2025

Opportunities for diplomacy in the Indian Ocean will help secure Australia’s future in a multipolar world.

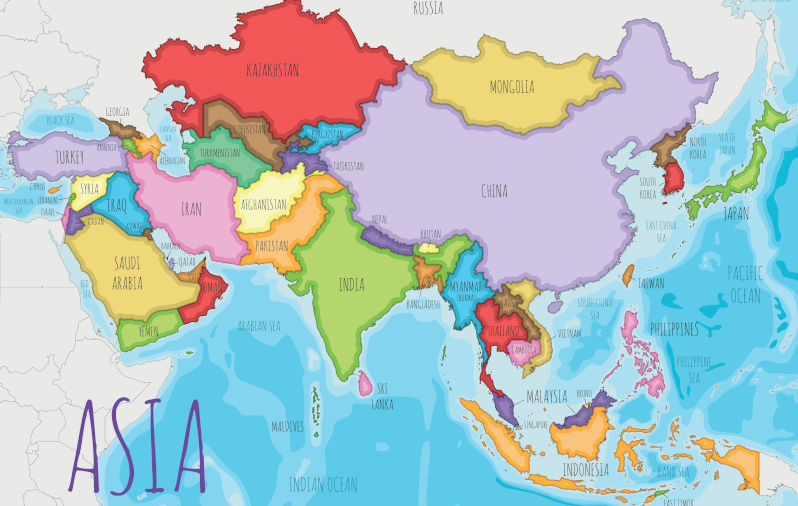

After the week that has been, it might be worth considering turning the other cheek. Here, looking away from China (and the United States) will remind Australian policymakers that the nation faces other directions too. That means looking west and towards the role India and Africa will continue to play as neighbours in our geopolitical community. While attention has rightly focused on East Asia for a long time with markets in China, South Korea and Japan; and ASEAN has captured the imagination in the first Albanese Government, we lack a sophisticated understanding of South Asia’s influence on our own strategy and a blindness to Africa at all. This remains the case despite growing diaspora communities here and their economic potential in future years.

In Hugh White’s recent Quarterly Essay, _Hard New World_, the inevitability and complexity of a multipolar world seems a fait accompli. This is not only a shift from American hegemony, but also the lack of return to a bipolar world such as in the Cold War. Now, we are dealing with relative centres of power and an altogether more fluid dynamic. Geographically speaking, we find our security in Asia, but it seems we tend to forget the role India will play in balancing China, in aiding Indonesia, and in thinking about Africa as a player in the global order. Australia’s East Coast persuasion has undermined its ability to grasp opportunities from places as diverse as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Kenya and South Africa, let alone places such as Oman and Mauritius. That means there is a chance now to play a more complete game of diplomacy.

There have been gestures towards change here, not least the creation of a Special Envoy for the Indian Ocean. Tim Watts fills that post now after his appointment as assistant minister for Foreign Affairs and his remit is backed by internal factional support. He is undoubtedly an intellectual in the context of a younger generation of parliamentarians and understands the complexity of the region. The appointment of an assistant minister is a welcome change, and speaking with officials one gets the sense that maritime security and environmental research will be the focus for the government here. And yet, what happens when we expand our idea of diplomatic engagement and centre the Indian Ocean in a national discussion?

At present, there is no minilateral diplomacy body that encourages effective partnerships with other nations here. There is, in short, no equivalent of APEC for the Indian Ocean. There are maxilateral bodies, with IORA ( Indian Ocean Rim Authority) being prime among them. But they are unwieldy and have not had great success since being founded 30 years ago. By including every one of the littoral Indian Ocean states, the body has undermined its chances of effectiveness. There is the Francophone Indian Ocean Commission, operating since 1984, but Australia is excluded from that; it is essentially a single organisation with a small geographic footprint.

If we are serious about living in a multipolar world and if we take our geography seriously too, we need to promote a new minilateral body for Indian Ocean dialogue. Call this INDOCC – Indian Ocean Co-operation of Countries. That would be an opportunity for the Albanese Government to keep negotiating the changing landscape with attention paid to our status as a middle power. That means leveraging our geography in a complete way to bring India, Indonesia, South Africa, Oman and Kenya to the table. With observers in Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Thailand, it could be a way to ensure prosperity, security and stability in a post-American world. They could then invite dialogue partners much like the G7 invited Albanese himself to Canada this year.

The more instructive lesson from this is that the international rules-based order is being redrawn. In that volatility, there are opportunities for how Australia leads new relationships. With an awareness that the solidity has melted, we might begin by looking anew at maritime issues beyond submarines and sun cables. If Australia is to successfully manage its place in the world, we might not only find our security with, and in, Asia, we might begin to see our peace and prosperity tied up with India and Africa, and to take a leadership position in facilitating good relations between neighbours who often forget to look right next door.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.