Forecasting the impact of Sino-Indian relations on changing world order

November 17, 2025

Geopolitics is in shock. Agile strategic thinking must acknowledge and respond to qualitative changes to the world order. A new “New World Order” is emerging.

During the coalition-building against Saddam Hussein, president George H.W. Bush had popularised the term “New World Order”, to mean “where diverse nations are drawn together in common cause to achieve the universal claims of humanity”. The “Peace President”, Donald J. Trump, however, draws on domestic politics to wage a fierce international campaign against “equality, diversity and inclusiveness". The universal claims of humanity are discredited as “woke-ism”. Ba-da-ding, ba-da-boom deal-making is more important than getting together “in common cause”. In the absence of a coherent uplifting US strategy, the relations between India and China are likely to significantly influence the rapidly changing world order.

Sino-Indian relations may reflect differences of ideology and state system, but have not served as the exclusive basis of their relations. These states gladly back the UN. They identify with the common cause of equal state sovereignty vis-à-vis imperialism, neocolonialism and the inequality of great power politics. In fact, it is surprising that there has not been a much stronger symbiotic relationship between the world’s two most populous states. India and China do share a long border. Arguably, too much analytical emphasis has been placed on territorial issues. The incredibly short 1962 “border war” set off alarm bells, disrupting the leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement, but it did not initiate a lasting trend of open warfare. The handling of such a contentious border might even be cast as a success story. India and China have worked out an institutional approach to avoid full-scale war, by keeping communications open during crisis. Under the aegis of The Working Mechanism for Consultation and Co-ordination, the ongoing regular meetings of Corp Commanders dealing with operational issues is co-ordinated with the meetings of Special Representatives, so as to stabilise the border.

History offers important perspective on today’s possibilities. In the 1950s, India and China shared the necessity of independence in the context of brand-new national government and existential economic and social dislocation. While China coped with the traumatic consequences of civil war, India passed through the trauma of Mountbatten’s 1947 partition. The two struggling new states avoided narrowing their foreign policy options within closed Cold War alliances. The momentous emergence of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 did not seriously confound Sino-Indian relations. Communist victory did not result in serious conflict with India’s new parliamentary democracy. The battle-tested PLA had grown by leaps and bounds in the civil war, but when it moved into Tibet, India and China did not want to go to war. Nehru spread Gandhi’s message of peace. War between two great populous civilisations was unthinkable.

Sino-Indian idealism grew out of mutual national necessity. Recall the significance of the 1954 bilateral accord between China and India, recognising “The Tibet Region of China”. Things could have gone terribly wrong. Instead, the Tibet Agreement celebrated for the first time “Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence”, (or Panchseel) namely “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s affairs, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful co-existence”. Prime minister Nehru told the Lok Sabha, “This Agreement is good not only for our country, but the whole of Asia and the rest of the world.” Premier Zhou Enlai responded, toasting Nehru for India’s support during the war of resistance against Japan, for India’s speedy diplomatic recognition, support for the Chinese position in the UN and its supervisory role in the Indo-China armistice.

The five principles later served as the cornerstone for the Non-Aligned Movement. They were stated time and again in the 1955 documents of the Bandung Afro-Asian Conference, in the US-China Shanghai Communiques, in the founding principles of ASEAN, outlined in the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia and mirrored in the documents of the BRIC and the “Shanghai Spirit” of the Shanghai Co-operative Organisation. They have been constantly eulogised as consistent with the UN Charter and they have been stated in China’s bilateral relations with the US and Russia. Today these principles remain at the core of Chinese foreign policy and are duly re-stated in top-level Sino-Indian exchanges. India now makes less reference to the “five principles of peaceful co-existence”, but the interest in independence, sovereign equality and mutual respect within co-operative multilateralism retains significant policy prominence. Both countries insist they will foster peace and the family of nations and cultures. Both countries prefer flexible “strategic partnerships” to formal military alliance.

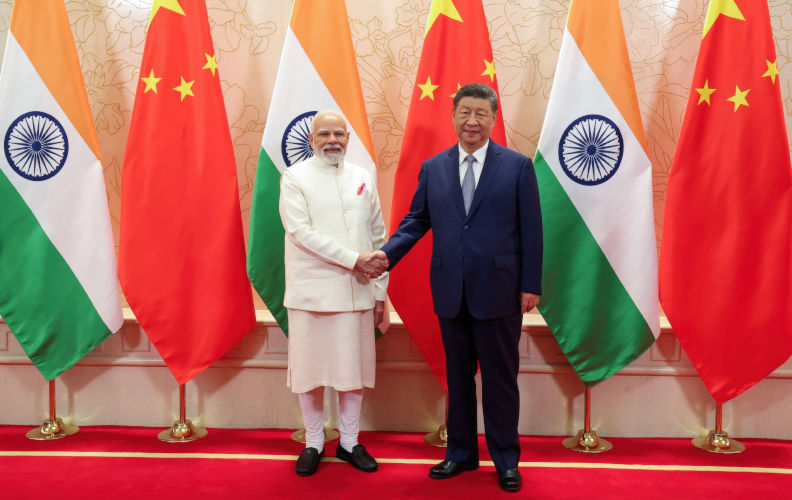

The more Trump deepens protectionism, “re-aligns” US foreign aid and ignores the socioeconomic dimensions of long-term development and UN “peace-making”, the more states, may adapt to non-alignment to defend their own national interests. Where does Trump stand? He conflates liberalism and communism. Is he in or out when it comes to challenging autocracy? He seems more concerned to elevate his domestic attack on “woke-ism” to the international stage. His campaign against “equality, diversity, and inclusiveness” challenges the five principles and UN values. Dismissing the UN in his 23 September address to the General Assembly, Trump claimed only he had to make up for the UN’s weakness in solving “seven unendable wars”. His patronising self-glorification was offensive. How did India and China respond? Both offered helpfully balanced perspective on progressive multilateralism and the related prospect for UN reform. India’s foreign minister and prime minister, however, corrected Trump, emphasising that India always exercises its strategic autonomy and had never requested American mediation.

Whatever happened to mutual respect and equality in the common cause of humanity? Trump has binned the five principles. Chinese and Indian support for UN collective security and common development is more compatible with the “rules-based order” than what is implied in Trump’s impolitic transactionalism, which creates shrill dissonance with Asian values that prefer patient consensus between modest equals. China and India together could achieve unexpected precedence and influence. Their “independence” rose above the Cold War ideology and system. Both India and China remain committed to the core values, underlying UN organisation and principles. They are still not inclined to enter into formal military alliances, preferring peaceful negotiation and collective security. They do not welcome the current tariff wars. In a sign of things to come, China and Russia, in September 2023, endorsed India’s permanent membership on the Security Council.This recognised India’s novel importance, stressing inclusivity as the basis for UN reform. “Like-minded” states in the West need quickly to develop a more sophisticated awareness of the implications of changes to the world order. The “West’s” focus on AUKUS and the Quad, for example, has been too exclusive.

India and China in 2025 are not India and China in 1948. In the fullness of time, Trump’s much touted “Golden Age” may belong to China and India. Both countries have burgeoning populations and have experienced rapid modernisation. In 2025, the US population accounts for only 4.2% of world population. The Chinese and Indian populations together account for 35.5%. While the US neglects its own contribution to the New World Order, they are for the most part on the right side of history. The commonality of foreign policy principles and non-aligned world view, animates these two huge nation-state civilisations that would imbue world affairs with their great traditions. China and India refuse to play the “great game”, focusing instead on the more peaceful elements of the Westphalian heritage, stressing sovereignty and independence, as increasingly legitimated in reference to Confucian “harmony” and Indian dharma to support just development and to counter the exclusivity of Cold War bloc politics.

India and China may compete for the leadership of the Global South, but such competition will likely be tempered. There is a positive and familiar background that India and China could draw on with even greater effect than in the 1950s. The evolution of their relations could have a serious impact on a world order in transition. Trump, however, may end up like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, serving as Hamlet’s “engineer hoist with his own petard”. (The “engineer” lays siege to a city wall and is blown away while “hoisting” his own bomb, or “petard”.) Trump’s culture wars, his protectionism, his belittling posturing, his my-way-or-the-highway transactionalism may foster increasingly harmonious Sino-Indian relations. Today’s competing geopolitical realities of contemporary society may be mediated with Sino-Indian advocacy of the substantive idealism, embedded in the five principles. The US may have fathered the UN, but India and China may yet become its greatest patrons. India and China have long subscribed to strategies of independence versus bloc politics, and this sets a powerful precedent for future Sino-Indian relations that will facilitate a new “New World Order”.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.