Australia: An Electric Vehicle Battery manufacturing powerhouse?

October 7, 2022

Is it too late for Australia to enter the global market for Electric Vehicle Battery (EVB) manufacturing? It has become apparent that Australias exit in 2016 from local car production has made it more difficult for us to participate fully in one of the 21st centurys fastest growing, technically advanced and environmentally critical industries.

Kent Masters, CEO of US-based global battery minerals company Albemarle, certainly thinks so. The case he makes is compelling. Rising geopolitical risks mean car makers want EVB production close to car assembly plants, and governments in nations with car makers are giving big incentives for more local battery production, as in the US Inflation Reduction Act, to close the loop in car supply chains. Moreover, car makers themselves are looking to a future when the main source of inputs to EV batteries will be local recycling of spent batteries.

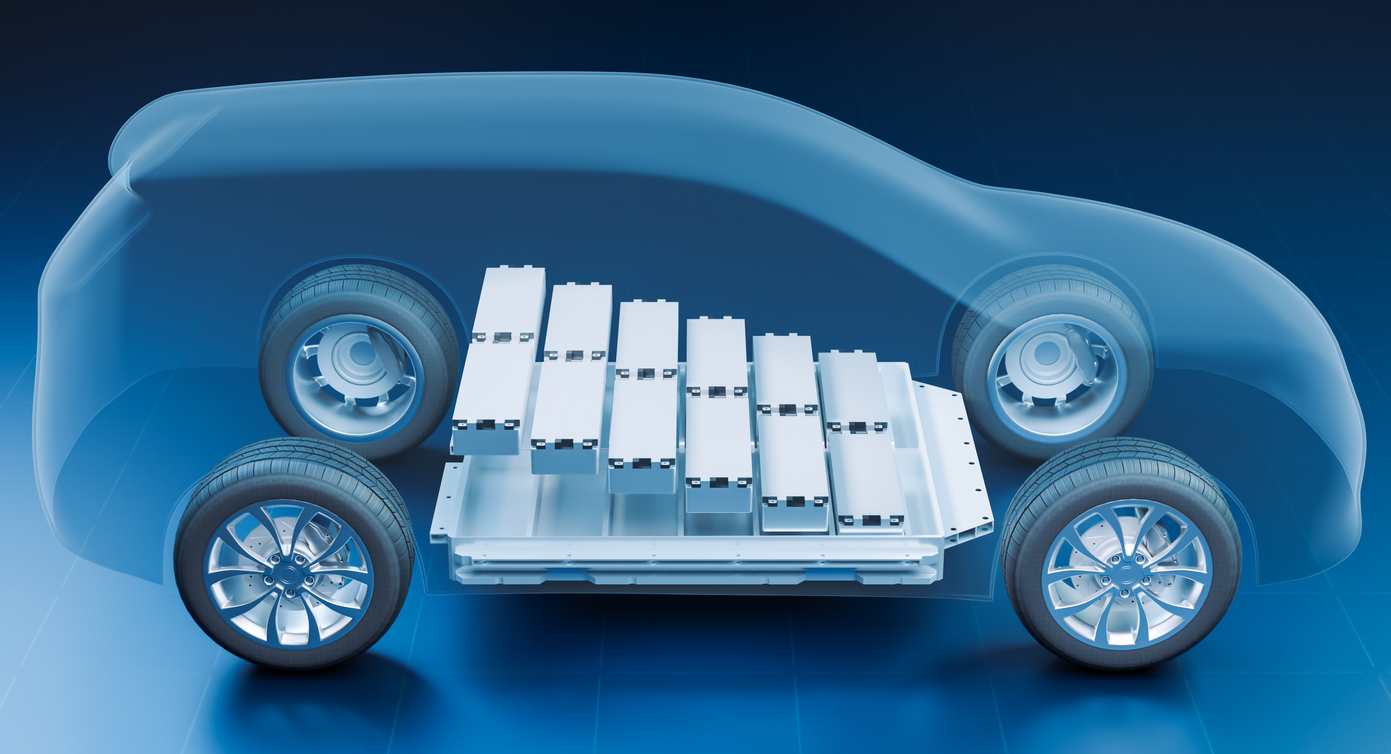

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) batteries constitute 30-40% of the price of an EV, capturing this value locally, rather than importing it, gives a powerful impetus to these strategies. Six years ago, the former LNP government decided the nation could do without a local car industry, indeed, it goaded the industry to leave. With no car industry and minimal government support for either a nascent battery industry or uptake of EVs, what are the realistic prospects for EVB making in Australia?

Australia accounts for 50% of global lithium production and has 25% of global reserves, yet it captures just 0.53% of the value of its lithium ore exported and processed into EVBs. Even if all Australian lithium ore is subject to the next basic level of processing, converted into lithium hydroxide, highly unlikely under current policy settings, the value share only increases to 1.4%. Close to 75% of the value chain is provided by the final two stages, battery cell manufacture and battery pack/systems assembly, all of which occurs in Korea, Japan, China, the EU and US. The IEA anticipates a 600% increase in demand for EVBs to 2030.

On the positive side Australia is not only a major global producer of lithium ore, but Geoscience Australia records it also has abundant reserves of all the essential mineral inputs to support the lithium-ion battery supply chain such as graphite, iron, nickel and manganese. Arguably one of the major advantages the nation has, if it manages the investment attraction and planning properly, is a vast supply of cheap renewable energy. Making EVBs, counting all the energy used in the total supply chain from mine to the final product installed in a car, is very energy intensive. For example, up to 15 tonnes of CO2 is released just to mine every tonne of hard-rock lithium.

Other research finds that around 50% of lifetime CO2 emissions of EVBs are caused by battery production, with the rest coming from powering the EV from the grid. (This assumes electricity is sourced from coal fired power stations). Estimates of energy usage in giga-scale battery plants range from 5065 kWh of electricity per kWh of battery capacity, excluding mining and processing of raw materials. In other words, a 1gigawatt hour (GWh) EVB factory will consume a minimum of 50 GWh hours per annum. (Most battery factories globally are much larger than 1 GWh. A GWh, is a unit of energy representing one billion (109) watt hours and is equivalent to one million kilowatt hours).

However, the scale of the energy transformation to electrify consumption and production in Australian is truly monumental. To put it in perspective, NSW alone consumes 145,950 GWh equivalent of petroleum for transport per year (derived from NSW EPA 2022: Figure 3.2). In 2018-19 NSW petroleum use for transport was 525 petajoules (PJ) of energy annually. The conversion factor of PJ to GWh is 1: 278. This is more than double the total energy equivalent of electricity production in NSW and 11 times the equivalent total renewable electricity produced per year. Converting this petroleum power source to batteries will require astronomical new renewable energy generation, as too will the power required to make batteries.

Any nation or region having plentiful and cheap renewable electricity employed in the full supply chain from mine to final EVB will have a major advantage over other regions which, due to climate or natural endowment, will be renewable energy constrained. The global hunt is on not just for green lithium but also ironically for green batteries. In China, which produces about 70% of the worlds EVBs, 50% of grid power comes from coal. This is simply not sustainable. Australia has the brain power and potential renewable energy capacity to take EVB production to the next stage, with the support of institutions such as the Future Battery Industries CRC Ltd (https://fbicrc.com.au/), the CSIRO and some far-sighted industrialists such as Andrew Forrest.

Like many high-tech activities, all critical stages of EVB production are highly concentrated in a few firms. Three companies control 70% of final EVB production. The patents, technical know-how and experience in constructing and optimising EVB plants is tightly held within these few global firms. Establishing a large scale EVB industry, by definition, means dealing with these large players. The strategic significance of batteries, their scale of demand growth and the highly concentrated markets in their production explain why all developed nations and even developing nations such as Indonesia have adopted a whatever it takes stance in deploying industrial policies to retain and attract more EVB investment.

The lost decade of environmental and industrial policy under the LNP was a high-fidelity reproduction of the long-term instinctual response of the national bureaucracy and politicians to never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity when it comes to further value-adding our abundant resources. To the rest of the world, Australia is a commodity producing Sisyphus, where the Canberra economic gods have forever condemned the nation to rolling large lumps of iron ore and coal to the nearest port. For now, our third world trade and industrial structure pays for our sophisticated first world taste in imports. The question for the newly elected Labor government is not can we afford to become a global leader in EVBs, but can we afford to not to be?

Shared article from Financial Review.