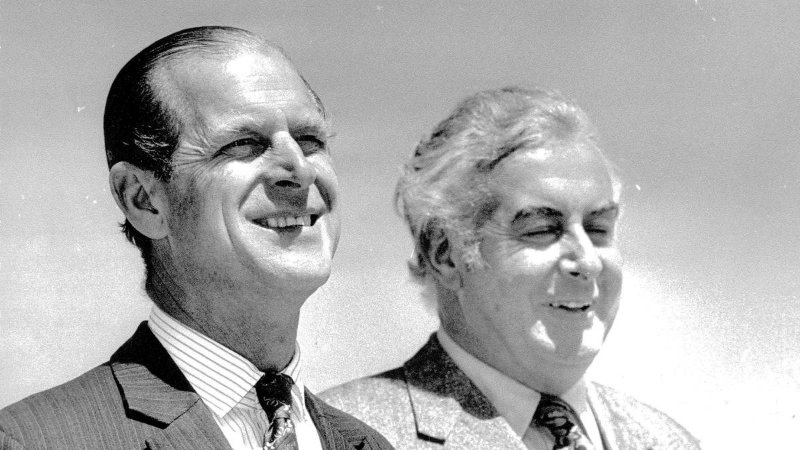

Prince Philip and Gough Whitlam: the story The Crown forgot. A socialist arsehole- A Repost

September 13, 2022

_As Gough Whitlam put it- I am the first prime minister since Sir Robert Menzies who has been able to survive a second visit from Prince Phillip’. The long-standing consort described Whitlam as ‘a socialist arsehole’

_

This article was first published on May 4, 2021.

Prince Philip’s death was a reminder that the Queens reign is nearing an end, bringing with it questions over the future of the monarchy.

It could not have escaped anyones attention that Prince Philip died three weeks ago. He was 99 years old, had a history of heart trouble and, as the Queens long-standing consort, was as familiar as the Monarch herself. With his death a remarkable transformation took place as saturation media coverage recast the public image of the brash, boorish, ladies man into a model of virtue, tact, and unimpeachable rectitude.

The Australian, a paragon of historical revisionism, saw Prince Philip as a man with the common touch, a Royal larrikin, a moderniser. To the Daily Mirror he was asensitive, poetry-loving, radical. It was all a bit absurd.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth and Baron Greenwich, also called Philip Mountbatten, born Philippos Andreou of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderberg-Glcksburg, Prince of Greece and Denmark, was reduced to a dutiful, rather stolid figure, far less interesting in death than he had been in life. Respecting the recently departed is one thing, rewriting them is quite another.

Now that a decent interval has passed, we can recall Prince Philip more correctly as a relict of ancient European internecine royalty down to its lastsou, a purveyor of horses and hounds, shooting and carriages, with a fine pedigree in offensive, racist remarks.In the coded language of his death these unfortunate traits were recast as light-hearted, humorous, direct, and always and only termed gaffes. The senior Nazi positions of his sisters and brothers-in-law, banned from his wedding to Princess Elizabeth in 1947 given its proximity to the war, were hidden in the oblique melange of German relatives or family connections.

_The Sunday Times_took this exercise in royal absolution too far, suggesting in a front-page apologia that people secretly rather enjoyed Philips gaffes about slitty eyes, for which it was forced to apologise following complaints that this trivialised racism at a time when violence against people of Asian background in the UK was escalating. Professor Kehinde Andrews condemned the sanitised image of Prince Philip as masking old-school racism; Painting him as a benign, cuddly uncle of the nation is simply untrue When he says things about Chinese people’s eyes and chucking spears [it] would not be tolerated anywhere else nor from anyone else.

Stripping away the faade of familiarity and the Prince as one of us, the simple fact is that the royal family is not one of us and never can be. This is not just a statement of political fact it is a legal one, acknowledging the unique privileges and prerogatives of royal blood, including even exemptions from the law itself. Philips elevation to Prince, a title bestowed by the Queen in 1957, lifted him beyond the range of a subpoenain the UK just as it does Prince Andrew, which is particularly significant given his current predicament. The Queen is beyond the reach of the law under sovereign immunity, ascivil and criminal proceedings cannot be taken against the Sovereign. The royal family is exempt from Freedom of Information laws and exercises an iron-clad secrecy over its activities, with its own Royal Archives to privately house any documents it considers personal, away from public view.

The extent of the greatest of these arcane royal privileges, the Constitutional outrage of the Queens consent, was only recently uncovered. Through this exceptional personal consent provision the Queen vets all legislation that might affect her, or Prince Charless, financial interests before it goes to parliament. It represents the personal use of a residual imperial power for vast private gain. _The Guardian_s revelation of its broad application provides a window onto the way in which royal political power is wielded secretly and in private, through a process available by birthright to the royal family alone.

Although Buckingham Palace insists that the constitutional principle of the political neutrality of the Crown is scrupulously adhered to, the use of the Queens consent is just one of several revelations which have exposed this apparent political indifference as a myth, maintained only by secrecy. The Palace letters, released after the High Court success of my legal action against the National Archives, revealed the Queens regular communications with the Governor-General Sir John Kerr on political matters of the greatest significance, including Kerrs discretionary powers and the prospective dismissal of the Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam; while Prince Charless spider memos, released after a decade of legal battles by_The Guardian_, revealed his secret personal lobbying of the Blair government over policy matters of interest to our future King.

An exchange between Prince Philip and Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in 1973 highlights this continuing presumption of personal political influence, and Whitlams refusal to go along with it. Philip wrote to Whitlam in March 1973, setting out his views on the protection and control of wild species in Australia among a range of conservation concerns. Although he was writing about conservation matters, Prince Philip stressed that he was not writing as president of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) as he then was. The letter was on Buckingham Palace letterhead and was entirely on a personal basis.

Missed in the few commentaries on this letter, is the implication of Philips entre into the policy arena for the political neutrality of the Crown. This can be seen most clearly in his urging of Whitlam against the introduction of a blanket system of national parks in favour of special reserves which could be individually managed for various purposes, rather than a formalised system of nationally funded, resourced and protected national parks. Philip voiced his well-known concerns for conservation matters, in particular the protection of Kakadu which he termed the hottest of the potatoes. As the direct responsibility of the federal government, he wrote, this could become embarrassing for the government and he urged Whitlam to create a special reserve, rather than a national park.

Given the years of policy work that had gone into the governments plans for a comprehensive system of national parks, a centrepiece of Whitlams environmental agenda, Prince Philips directive was condescending and ill-informed, an example of what a former private secretary described as his tendency to reach prejudiced positions without the information to do so. In calling for Kakadu to be protected, while at the same time lobbying Whitlam against a blanket system of national parks, Prince Philip appeared entirely ignorant of the governments policies and their breadth. The managed system of national parks established by Whitlam under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 was precisely the means through which Kakadu National Park was created and its heritage protection ensured. It is now Australias largest national park and in 2007 was added to the National Heritage List.

It was not the gratuitous personal political advice from Prince Philip which stung Whitlam, he could and did simply ignore that, it was the breach of protocol it involved. The first hint of his displeasure was in his reply, which came in the form of notes setting out the complicated history of Kakadu. Philips response was curt and ultimately dismissive, the problem remains. That Whitlam was still smarting over this political intercession was apparent during Philips return visit with the Queen later that year for the opening of the Sydney Opera House, to which the Prime Minister in an exceptional partisan snub had not been invited by the NSW Liberal Premier, Sir Robert Askin.

At a speech in Canberra in the presence of Prince Philip, Whitlam pointed to Philips many worthy causes and professed to occasionally feel[ing] envious that governments spend millions of dollars and receive no gratitude, to find that all His Royal Highness has to do is attach his name to a letterhead. Two days later, at a parliamentary luncheon in honour of the Queen and Prince Philip, Whitlam was at his biting, injudicious best, describing Philip as the nemesis of Australian prime ministers; I am the first prime minister since Sir Robert Menzies who has been able to survive a second visit from Prince Phillip At last the jinx has been broken. Prince Phillip has abandoned his role as the nemesis of Australian prime ministers.

From the democratic seat of Parliament itself, Whitlam reminded his captive and no doubt shocked royal audience of their political place they had none. We had misgivings, Whitlam continued blithely, because the last Phillip who was a consort to the Queen of England [Philip of Spain] did play rather too strong a political role. Now, of course, Prince Phillip has eschewed all forms of political activity.

It was possibly the closest thing to a public dressing-down Prince Philip had ever received and, in the presence of the Queen, this was humiliating, a moment of hubris. Little wonder that he harboured a profound antipathy towards Whitlam. A member of the royal household recalled his shock at hearing Prince Philip in a raised and irate voice unleash a vituperative outburst against that socialist arsehole Gough Whitlam, whom he never wished to speak to again.

In his hostile assessment of Whitlam, Philip was not alone. His uncle and mentor, Lord Louis Mountbatten, expressed his strongest support and admiration for Governor-General Sir John Kerrs dismissal of Whitlam, as did Prince Charles. Charles and Mountbatten wrote near identical letters of support to Kerr in the weeks after the dismissal, praising his courageous and correct action, a view which Kerr believed was shared by others in the royal family.

The death of Prince Philip marks a point of transition. It is a reminder that the Queens long-running reign is nearing an end, bringing with it questions over the future of the monarchy, of inherited title as political power, in a democracy. The continuing denial of any political involvement by the royal family - a family with its own channel of policy advice to government, its own means of vetting legislation, its secret personal communications with ministers, governors-general and prime ministers - is a sophistry, and a fraud against the Australian people. If we are to continue with this system of constitutional monarchy, with the British monarch as our head of state by birthright and not by choice, we should at the very least be truthful about it.