Professor Wang Gungwu: important recent China reflections

September 5, 2024

Prof Wang Gungwu, who is now 94, is an historian without equal. When someone alerted me that he would be giving an online lecture at HELP University in Kuala Lumpur on 10 August, I lost no time in signing up for a seat at the university’s Damansara auditorium.

Well before the present US-China tensions, Prof Wang, in a lecture he gave at the National University of Singapore in 2016, was already talking about how the South China Sea was becoming a big power pond, though no one could imagine how the relationship between the US and China would sour subsequently.

In this lecture, he spoke for more than an hour on the events leading to China’s rise as a world power in the modern era.

To Prof. Wang, the watershed year in the US-China relationship was 2008, when the world suffered a financial crisis. It was China that bailed out America. And this awakened the US. How can a protégé become stronger than the master?

Prof Wang also touched on the term world power, a notion which had not existed until the West began to colonise the world. Even the US was not one until after the end of World War II. And now China is being seen as one.

It is now a paramount US obsession to contain China, and because of its constant muscle-flexing in front of China’s doorsteps — in the name of upholding free navigation and protecting its vassals and allies in the region — it has also created an obsession on China’s part to build its naval might. The region is now gripped by two opposing obsessions!

However, Prof Wang was a little ambivalent on the legitimacy of China’s claims in its disputes with other claimants in the region. He argues that maritime boundaries are almost impossible to determine. China’s claim is entirely borne out of historical records – from the Ming and Qing dynasties. In fact, the entire sea was virtually under complete Japanese control until after the conclusion of World War II. After this, the sovereignty of the islands in the South China Sea was supposed to revert to China, which was governed by the Kuomintang as the Republic of China.

In 1949, the Kuomintang Government fled to Taiwan after its defeat in the Chinese Civil War and the People’s Republic of China now says it is the rightful owner of these islands.

In fielding a question, Prof Wang said the Nine-Dash Line, as it appeared in maps published by the Kuomintang Government and PRC, had historically never been objected to, contested, or challenged by any party until more recently. He explained that this is probably because China was no threat to any power when the map was first drawn, and [in the 1950s and 1960s] the PRC was not a member of the UN, hence no one paid any attention or placed importance on this line at that time.

Since no one contested these claims dating back to the Kuomintang, Republic of China period, these maps formed the legal basis of China’s assertion on the legality of this line. However, he also said there are also historical records to support such assertions.

In a recent interview with SCMP, Dr Wu Shicun (吴士存), the founder of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in China, said that the XiSha Islands (西沙群岛,Paracel Islands) had long been mapped out during the Ming dynasty and were Chinese possessions.

However, in the wake of Imperial Japan’s seizure of northeast China, France in 1931 took control of nine islands and reefs, including **ZhongYe Dao (**中业岛, Thitu Island) in the South China Sea. All these are in the NanSha Islands cluster (南沙群島,Spratly Islands), though.

When China was in the grip of the Cultural Revolution, the Philippines under the then Marcos Senior leadership, sent its military to take over a number of islands in Nansha including FeiXin Dao (費信島, Flat Island) and ZhongYe Dao. This was in the 1970s. As both Beijing and Taipei did not respond militarily, the Philippines conducted five more military operations and took over eight more Chinese islands and reefs. RenAi Jiao (仁爱礁Second Thomas Shoal) was not amongst them, though.

Although Dr Wu says these NanSha islands and reefs were originally China’s, he did not quite substantiate his assertion with more solid evidence, in my view. He did say that Beijing has never claimed that the whole of the South China Sea belongs to China, nonetheless, he contends that these islands and reefs should all be returned to the Chinese people.

In the absence of any legitimate record, I find it difficult to support positions taken by people like Dr Wu, even though it was obvious that the only country which had an intimate knowledge of the South China Sea was certainly China.

But I also find it difficult to support the Philippines’ claim. The Filipinos’ concept of nationhood did not arise until the late 1800s and seas beyond the main islands were rainbows to them.

I recently read an opinion by Professor Anthony Carty (profile below) who had gone through British and French archives, spanning from the 1880s to the late 1970s, to look at the historical understanding of the sovereignty of NanSha Islands. He discovered that “the archives demonstrate, taken as a whole, that it is the view of the British and French legal experts that as a matter of international law, the XiSha Islands and the NanSha Islands are Chinese territory.”

With respect to NanSha, he says “French legal advice was that France never completed an effective occupation of the Spratlys, and they abandoned them completely in 1956”. In the 1930s, they recognised that the Spratlys had always been home to Chinese fishermen from Hainan and Guangdong. There had never been any Vietnamese or Philippine connection and French interference had only been in its own name and not that of Vietnam. It is the British who then drew a decisive conclusion, from all the French and British records available, that the Chinese were the owners of the Spratlys, a legal position certified as part of British Cabinet records in 1974.

Interestingly, he also discovered a record in the US National Archives, circa mid-1950s, in which the under-secretary of state says the Filipinos have no claim to the Spratlys, though it is in the US interest to encourage them to make a claim anyway to keep Communist China out of the area.

Be that as it may, an arbitral tribunal in 2016 ruled in favour of the Philippines on most of its submissions. However, it clarified that while it would not “rule on any question of sovereignty … and would not delimit any maritime boundary”, China’s historic rights claims over maritime areas (as opposed to land masses and territorial waters) within the “nine-dash line” have no lawful effect unless entitlement is consistent with the UNCLOS. China, which did not participate, rejected the ruling, as did Taiwan.

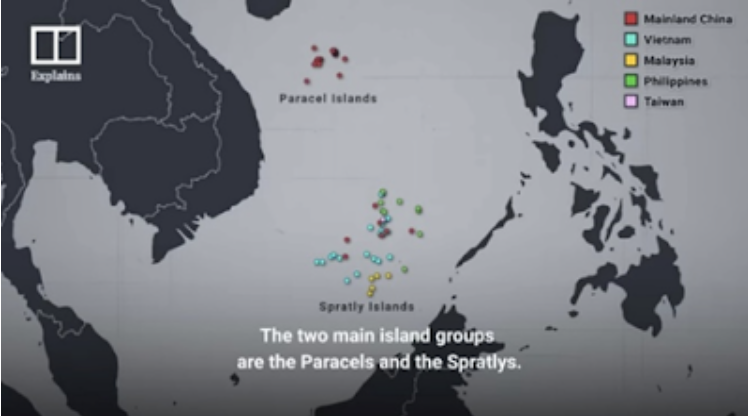

China still might be fighting an uphill battle. The South China Sea is full of players now. The map below shows how it has been divided based on oil and gas interests, though there are overlapping claims in many parts. No matter how strong China’s legal position is with respect to XiSha and NanSha, it will have to contend with the Vietnamese in the former and the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei or even Indonesia in the latter.

Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia are likely to be able to come to terms with China on the pond’s resources. I do not see that this route will be possible with the Philippines, as long as Marcos Junior is helming the country.

But as far as China is concerned, its military and naval control (not ownership) over the pond is non-negotiable, for it means life or death for China.

The possession of RenAi Jiao and HuangYan Dao (黄岩岛, the Scarborough Shoal) is absolutely important to China – as long as America and its hoodlums seek to use the Philippines to contain China.

Maybe China should say this louder and clearer to the world.

This is a lightly-edited version of a report on a recent presentation by the renowned Sinologist and historian, Professor Wang Gungwu. The original report can be accessed here.