Quad in trouble in new cold war.

March 23, 2022

_For those in Australia clinging to the Indo-Pacific as the titular proof of a new regional zeitgeist, where India is concerned, they are relying on a strategic partner that simply does not exist.

_

Scott Morrisons Americanisation of Australian foreign policy is troubling considering the high economic costs of imposing sanctions on China should it give aid to Russia over Ukraine.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine moves into a bloodier phase, attempts to divine its meaning for the future intensify.

Instant myths are being created out of the emotion of the moment. And masks are being peeled away.

We are told by some that a new world is being born. By others that freedom is fading into the twilight. Platoons of experts, at ease in their self-made war cabinet rooms, push military escalation with blithe indifference to the horrible consequences that may follow.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison, in his latest trawl through the back catalogue of American neo-conservative rhetoric the very talk which gave us the Iraq war already has his slogan: the arc of autocracy.

As analyst Elena Collinson has shown in The China Consensus, a report for the Australia-China Relations Institute, Morrison now embraces the ideological worldview he eschewed until last year.

It is true the Wests mobilisation against Russias outrage has put paid to fears about its decline. A snowballing, US-led coalition of democracies now has its new anti-authoritarian crusade. But uncertainties remain.

The fundamental changes wrought in world geopolitics point to the emergence of a new cold war. What remains at issue is whether that extends to China.

Brookings Ryan Hass argues that Chinas subsequent actions may well validate the fault line between democracy and authoritarianism. But he deems it premature to automatically default to such a conclusion. Hass suggests that at the very least the tools of American statecraft be fully mobilised to test whether Beijings approach to Russia is set in stone.

There has been condemnation of Chinas stance of benevolent neutrality in the Ukrainian conflict.

Beijings diplomatic charm offensive now supports the Ukrainians plight. There are signs that it supports the drive to isolate Russia economically.

In China, however, we should be surprised by the harshness of the internal disquiet over its position on the war.

Hu Wei, a senior adviser to Chinas State Council, called on Beijing to cut ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin completely to help build Chinas international image and ease its relations with the US and the West.

As Geoff Raby argued in The Australian Financial Review last week, Chinese President Xi Jinping has potentially missed that chance and, by his equivocation and therefore complicity in Putins naked aggression, made the elites, and China more broadly, lose face.

In the US, President Joe Bidens handling of the war continues to receive broad support. Yet, some want the US to go harder, calling for a limited flight exclusion zone over Ukraine even if that brings on conflict with Russia.

The editor of US international relations bimonthly The National Interest, Jacob Heilbrunn, has discerned the re-mobilising of veterans of the Cold War and Iraq among Washington foreign policy hardliners. Former president Donald Trumps mockery of the hawks is but a distant memory, he writes, for it is now the case that a belief in the unabashed assertion of American power abroad, democracy promotion, and regime change is … gaining sway.

In the US magazine Commentary, which seeded so much of the neoconservative thinking on US foreign policy, editor John Podhoretz suggests neo-conservatism has once more a present urgency.

It should be deeply troubling that Morrison has come to echo strains of this thinking. Yet, it was probably inevitable that Australias deeper defence integration with the US military would ultimately lead to the Americanisation of Australian foreign policy rhetoric.

In his ringing declaration that Canberra would be in lockstep with the US in enforcing possible economic sanctions against China, there is nary any grasp from the Prime Minister of the possible high economic costs to Australia.

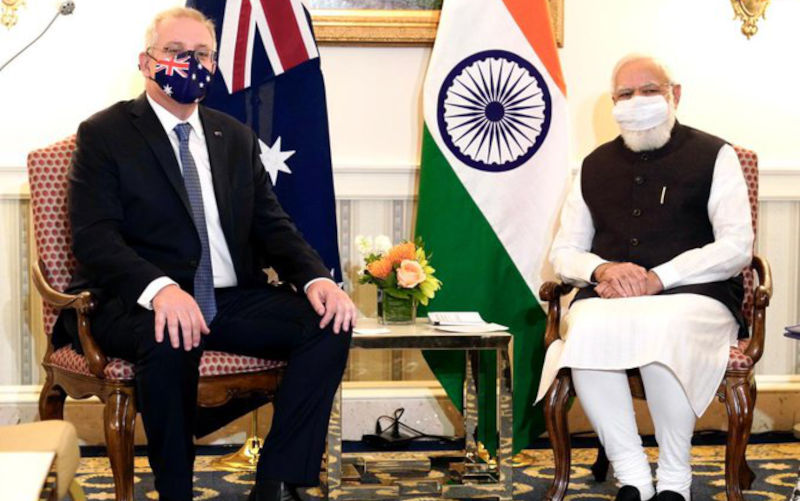

And what, pray, of India, a key Quad partner? Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been unmasked. He still looks to Russia for weapons in the event of possible conflict with China.

In the early days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, New Delhi abstained from a UN Security Council Resolution condemning Moscows actions. India then abstained from a General Assembly resolution based on the same language.

More recently, Indias central bank is reported to have commenced consultations on a rupee-rouble trade arrangement with Moscow, potentially enabling New Delhi to keep buying Russian energy exports and other goods.

Remarkably, the Australian National Universitys Rory Medcalf believes it is possible for Quad partners to effect nothing less than a fundamental sea change in Indias strategic culture.

Having long espoused the importance of values as the Quads binding agent, Medcalf now suggests that the Quad work to change Indias national interest calculations on Russia. There could hardly be a clearer case of allowing hope to dictate to judgment.

Journalist Greg Sheridan, knowing that India is part of the Quads raison detre, has had to concede that on the invasion of Ukraine, New Delhi has feet of clay. It cannot be hemmed in, he states, and must not be bullied.

For those in Australia clinging to the Indo-Pacific as the titular proof of a new regional zeitgeist, where India is concerned, they are relying on a strategic partner that simply does not exist.

This article is reposted with permission from AFR of 21 March, 2022