Quad queers its pitch: champions of democracy fail to walk the talk

December 8, 2021

The much-touted alliance designed to provide a counterweight to China is backsliding on its professed liberal principles, writes Brian Toohey.

President Joe Bidens virtual Summit of Democracies on December 9-10 will occur only three weeks after a reputable international institute added the US to its 2021 list of backsliding democracies. The Swedish-based Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance says there has been a visible deterioration of democracy in the US with a decline in civil liberties and increasing efforts to suppress voter participation in elections.

All members of the group of four countries called the Quad which was set up to contain China the US, Japan, India and Australia have serious democratic flaws. Japan is basically a one-party state. Its Liberal Democratic Party has been out of power for only four years and two months since it was founded in 1955.

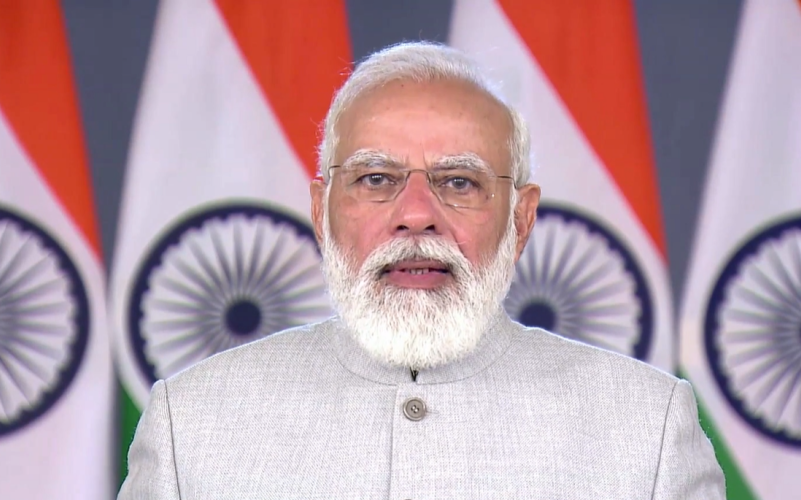

Indias behaviour has deteriorated severely since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BHP) Hindu supremacist government was elected in 2014. In 2020, the US government-funded Freedom House ranked India among the least free democracies and dropped it to the 83rd position on its ranking scale.It said in its 2020 report, The Indian governments alarming departures from democratic norms under Prime Minister Narendra Modi could blur the values-based distinction between Beijing and New Delhi.

In August 2019, the Modi government stripped the Muslim-dominated state of Jammu and Kashmir of its special constitutional status, converted it into two federally administered units and imposed a blackout on phone, internet and other contact. Modi deployed almost a million troops to the territory. Thousands of Kashmiris, including its political and social leaders, were jailed. Some restrictions have been removed, but Indian troops now routinely shoot government opponents in Kashmir they describe as terrorists.

The director of Human Rights Watch in Australia, Elaine Pearson, says Modis government has been using advanced technology to curtail rights at home as part of an escalating crackdown on freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. She says that even as his government promotes a more digitally connected India, it has shut down the internet more often than any other country, increasingly to silence peaceful protests and criticism of the government. This has not only denied millions of people their fundamental rights, but has also affected businesses and cost the Indian economy billions of dollars.

Pearson says Modi has been arresting more human rights defenders, journalists, students, and members of religious minorities in politically motivated cases under its counterterrorism, sedition and national security laws.

Indias Association for Democratic Reforms calculated that 43 per cent of the winners in the 2019 parliamentaryelection disclosed criminal charges against themselves:29 per cent disclosed significant criminal charges such as rape, murder, and kidnapping.Voters were notbothered. According to the Association,a candidate with a criminal record had a 15.5 per cent probability of winning, while one with a clean record had only a 4.7 per cent chance.

Political corruption is rife. In 2018, Modis government introduced electoral bonds to allow people and corporations, including foreigners, to buy bearer bonds from the State Bank of India and deposit them in political parties bank accounts. The BJP received 95 per cent of the money from the electoral bonds in 2017-18. Total donations grew strongly, allowing Indian political parties to spend $8.6 billion on the 2019 parliamentary elections compared to the $6.5 billion spent on US presidential and congressional contests in 2016. The BJPs Hindu supremacist policies also represent a change from previous bipartisan efforts to preserve India as an inclusive secular democracy into one which openly discriminates against Muslims.

Debasish Roy Chowdhury and John Keane say in their book, To Kill a Democracy: Indias passage to despotism, that decaying social substructures of Indian democracy openly contradict and degrade the high minded ideals the Indian Constitution which promised dignified solidarity to all its citizens.They show in graphic detail how India under Modi ranks near the bottom of numerous global indices, including those for nutrition, air and water quality, schooling and health. The Global Slavery Index estimates the 8 million Indians are living as modern slaves, the highest in the world.

Roy Chowdhury and Keane also note that Modis rise has transformed India from a constitutionally secular country into one that links citizenship to religion. Many illiterate Indians dont have a birth certificate. But if they are Muslims who are born there without one, they cannot be citizens. They say:

Under the new Hindutva despotism … 200 million Muslim citizens are the prime targets of institutionalised discrimination, police inaction, political propaganda, street level thuggery and lynching.

And back at home? Australias national security legislation deprives it of the right to be described as a liberal democracy.

Among other serious flaws, some these laws give the security and intelligence agencies the power to force companies and individuals to build new technology into their communication systems to insert covert surveillance software and defeat encryption. The basic protection of a court warrant does not exist. No other democratic country has these powers. Secret trials, long a hallmark of authoritarian countries, now protect an Australian government which behaved illegally in ordering their intelligence agencies to bug East Timors cabinet offices to engage in commercial espionage benefit and international petroleum company Woodside.

The latest example ofAustralia’s unjust security laws on the eve of a Summit of Democracies is a new power letting the government impose heavy sanctions on foreign officials supposedly responsible for malicious cyber attacks. No other country has a similar power relating to cyber attacks. No safeguards appear to exist to stop an innocent person from being the sanctioned by Australia.

The WikiLeaks release of the trove of CIA documents called Vault 7 shows the CIA as saying it can disguise the source of a malicious cyber act to make it look like a foreign actor is the culprit. One way to do this involves taking over a server in a foreign country that then appears to be responsible for a cyber attack. Similar agencies in other countries can do the same.

There is no good reason why Australia should not have demonstrate that an accusation is true before it savagely sanctions individuals.

Clinton Fernandes, a professor of international and political studies at the UNSW , says one of the CIA’s leaked documents reveal that program called the “Marble Framework” provides the capability to change the language of the source code from English to another language such as Russian or Farsi. Fernandes says, In the absence of a credible international institution that can provide checks and verification, all we have is one country blaming another and vice versa. That is not the level of proof that should apply to the imposition of severe penalties in a liberal democracy.

As for China, although its record remains bad, it seems to have improved in one respect. Under the headline Terror & tourism: Xinjiang eases its grip, but fear remains, the Associated Press reported on October 10 that the razor wire that once ringed public buildings in Chinas far north western Xinjiang region has nearly all gone. Reporter Dake Kang wrote:

Uyghur teenage boys, once a rare sight, now flirt with girls over pounding dance music at rollerblade rinks a sense of normality is creeping back in. But there is no doubt about who rules, and evidence of the terror of the last four years is everywhere.

“Its seen in Xinjiangs cities, where many historic centres have been bulldozed and the Islamic call to prayer no longer rings out. Its seen in Kashgar, where one mosque was converted into a caf, and a section of another has been turned into a tourist toilet. Its seen deep in the countryside, where Han Chinese officials run villages.

“And its seen in the fear that was ever-present, just below the surface, on two rare trips to Xinjiang I made for The Associated Press, one on a state-guided tour for the foreign press.”

The Chinese government in 2017 put 1 million, or more, Islamic Uyghurs into camps in Xinjiang because they were seen as a threat. Some Uyghurs have engaged in terrorist acts in China and Syria. Reuters reported in 2017 that Uyghur terrorists were operating in Syria with an IS terrorist group. Nevertheless, Chinas reaction in Xinjiang seemed to be out of proportion to the size of the threat.