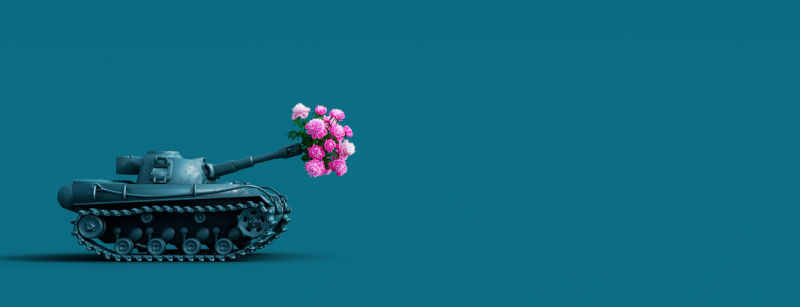

Rainbow alerts for peace, not red alerts for war

March 14, 2023

In their Red Alert for War, doom laden experts assembled by the Sydney Morning Herald forecast a war with China. Preoccupied with cybersecurity, biosecurity, with the weaponry available in military alliances, the experts speak the language of militarism and war but have nothing to say about peace. Yet the language of peace can inspire, not red alerts but rainbow visions to enhance life, not destroy it.

The trouble is that even in these dangerous times, speaking that language is not a policy priority and must overcome age old cultural and political obstacles.

In response to forecasts in the Red Alert for War, interviewers on mainstream Australian radio and television have asked who might win a war between the US & China, whether Australia as a US ally would be dragged into war, and how nuclear submarines might contribute to the countrys security. Still no questions about peace, let alone how promoting peace could replace an apparent fascination with war.

Australias Federal parliament may not be indifferent to peace but has not found time to debate policies to foster that goal. Former Senator Margaret Reynolds has expressed her regrets that there was a time when such issues would be discussed in the Senate or the House of Representatives, but no longer.

Over the past twenty years, other significant institutions have discouraged the study of peace and have limited the chances that peace with justice goals would influence domestic and foreign policy. With exceptions at the UNE and more recently the University of Melbourne, university peace centres have been closed. A flourishing Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney ceased when university management perceived staff activism in support of Palestinians on the West Bank, Tamils in Sri Lanka and the Indigenous people of West Papua as not a priority for an increasingly business oriented institution. Students were enthusiastic but activism for peace did nothing for a financial bottom line.

Closing peace centres ran parallel to the arrival and rise of university centres promoting strategic, security, defence studies and in the case of Kings College London a burgeoning war studies department. Concern with violence trumped interest in non-violence. Trade trumped human rights. In political and business management eyes, peace studies became an activity not worth funding, best conducted by volunteers, mostly women at week-ends.

At this time of wars co-existing with devastation from climate change, voices for peace need to be heard, their priorities more dominant in national conversations than the political excitement surrounding the purchase of nuclear powered submarines.

In any context or country, struggles to achieve peace with justice depend on literacy about universal human rights and on familiarity with the philosophy, language and practice of non-violence. Mahatma Gandhi taught that such a philosophy was not only a way of living but a law for life. Nuclear disarmament, Australia signing the treaty for the abolition of nuclear weapons, would illustrate the value of non violence, though critics say that such a step represents appeasement, better to prepare for war.

Students around the world speak of hopes for peace with justice and their fears that politicians from an older generation take little notice. University students in China have described a politics of identity. They wanted to be taken seriously. They spoke fluent English - I know no mandarin - and wanted to learn about the aspirations of young people from other countries, including Australia. Those aspirations referred to living and sharing, to fellowship and personal security.

Students in India, Japan and Brazil have insisted that the values and language of peace should affect their lives, not least in dealing with pandemics of domestic violence. Through the promotion of universal human rights, young women could experience security and respect, a complete end to gender based threats and discrimination. They highlighted links between domestic violence, bullying in the work place, the arms trade and devastation from wars.

Students knew of life enhancing chances if priorities for peace included defence of a precious environment. They followed the judgement of Indian physicist Vandana Shiva, recipient of the 2010 Sydney Peace Prize, who argues that advocacy of peace must address ecological destruction, climate chaos, the disappearance of species and water scarcity, each crisis a left over ruin of a war against the earth.

In his most recent Message for Peace, the influential secular Japanese Buddhist leader Daisaku Ikeda argues for the abolition of poverty, for the chances of equality for women, for the education of girls, for nuclear disarmament and for reform of the UN. That crowded agenda merits research, teaching and advocacy.

In popular and classical music, in pottery, painting and poetry, diverse artists passion for peace contributes hugely to ideals for a common humanity. Such creativity is non violent, usually inspiring and always offers alternatives to violence and war.

The Peace Symphony, Beethovens Ninth, and the libretto in the last movement, speak the language of peace. The composer said he wanted his final work to be influential inside and outside the concert hall. The words for the final chorus and soloists came from a poem Ode to Joy, the work of the German poet Schiller who wanted his lines to be a kiss for the whole earth.

Beethoven, Schiller and diverse other artists might not be dubbed experts for peace, but in the minds of millions, their creativity continues to celebrate justice and oppose war. Such peace promoting language has imagined a non violent rainbow vision for humanity, so life enhancing, so different to a red alert for war.