Red Alert: news media Sleep-Walking into US war propaganda

March 14, 2023

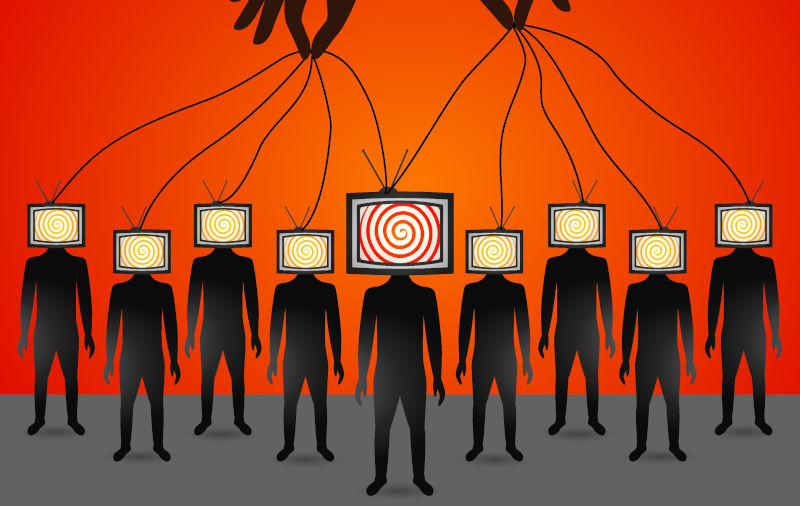

One of the best-known writers on public opinion, Walter Lippmann, tells us that every conflict is fought on two fronts: the battlefield and the minds of people via propaganda. We must remember that in time of war what is said on the enemys side of the front is always propaganda, and what is said on our side of the front is truth and righteousness.

_The Sydney Morning Herald_s Red Alert series seems to have the explicit aim of making the Australian public hostile towards and fearful of China, and nervous about their own lives in the future.

The series serves as a stark warning to the public of the real possibility that our mainstream media have entered a new phase in reporting on China. Starting in 2019_,_ one of The Herald__s promotional billboard and online slogans has said_:_ Chinas growing influence: If Beijings ambition affects Australias future. You deserve to know. In exposing Beijings ambitions, The Herald promises to shine a light on hidden influences using hard news to expose soft power. And in order to achieve this, the Herald promises to do whatever it takes to break the stories.

Note the last sentence: The Herald promised to do whatever it takes. It has certainly kept its promise although interestingly, this last promise now seems to have been removed from their website. If The Herald had decided to push its China threat agenda as early as 2019, it has now clearly decided to update its business model by officially sounding the horn of war.

Ours is a liberal democracy, and freedom of speech is vital. But the public in democratic countries must realise that totalitarian and authoritarian regimes do not have a monopoly on propaganda. As Noam Chomsky reminded us long ago, propaganda is harder to see in democracies than in totalitarian regimes because the media in democracies operate by manufacturing consent: propaganda is to a democracy what the bludgeon is to a totalitarian state.

And when Lippmann and Chomsky become relevant to the current discussion, we know that our democratic media are in trouble.

Perhaps a different kind of Red Alert is now warranted a Red Alert about a sharp decline in the news values of our media. This is because the sort of war rhetoric The Herald and many other mainstream media outlets are engaging in is extremely dangerous. It is perhaps for this reason that, for the first time, the ABCs Media Watch, which so far has not criticised the Australian medias China reporting, saw it necessary to take a stand on the Red Alerts series and call it irresponsible journalism.

The so-called journalism embodied by the Red Alert series is dangerous because war talk like this can actually make war more likely, for several reasons.

First, repeated claims of an imminent war with China that are made with little evidence serve to normalise war mongering as an acceptable speech act. Such a narrative strategy is part of the process of making the unimaginable imaginable. The history of Cold War journalism supplies us with plenty of evidence showing how the newspaper chains of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer the architects of yellow journalism actively fanned the flames of the Spanish-American War. In fact, as Ted Galen Carpenter, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, recounts, several months before the outbreak of war, one of Hearsts reporters wanted to go home from Cuba because there was no sign of war at all. Hearst reportedly ordered him to stay, saying, You furnish the pictures, and Ill furnish the war.

Second, few people would deny the structural and geopolitical challenges Australia faces today, and like any other country in the world, Australia has every right and obligation to defend itself. But prophecies of a war with China aim to legitimise the discourse of China as the nations enemy despite the fact that the current government is working hard to mend relations with China, despite the fact that China remains Australias biggest trading partner, and despite the fact that maintaining a working relationship with China on all fronts is crucial to Australias national interest. Repetitive war talk involving China as the enemy may gradually but surely cement the idea of China as our enemy as simple common sense a taken-for-granted background assumption that is no longer questionable or contestable. Even the ABCs seemingly genuine attempts at cool-headed and even-handed discussion about what would war with China look like have the presumably unintended consequence of creating a perception that war with China is a real and present prospect.

Third, narratives of an imminent war with China aim to prime the public by creating conditions of fear and uncertainty. While Thomas Hobbess argument on war has been subject to much debate, he is perhaps not completely wrong in believing that one of the root causes of all wars is disagreement. To Hobbes, as one writer sees it, nations go to war not just to fight for material resources to ensure their own survival, but because human beings are fragile, fearful, impressionable, and psychologically prickly creatures susceptible to ideological manipulation.

Fourth, by creating a nervous nation with a worried public facing an uncertain future, narratives of an imminent war aim to put pressure on the government to adopt a more hostile approach to China, knowing very well that the legitimacy of any state power rests on its capacity to win the support of the public. Moreover, the government may even find such media rhetoric helpful, given that it may help shore up public support to justify the eye-wateringly expensive defence expenditures which we see, for instance, in the announcement of the AUKUS deal. It is true that we have yet to see Labor rushing to endorse the sentiment behind the war rhetoric. But it is equally true that neither Albanese nor Wong has made any responses that firmly distance the government from it.

It is clearly with this sense of urgency that our first ambassador to China Stephen Fitzgerald recently called on the Labor government to repudiate such war hysteria.

This is not to say that Labor is not capable of making foreign policy decisions independently of the media. But media discourses about war with China could create a difficult, even unfavourable, context for political leaders to make sound decisions, hence undermining the governments ability to effectively conduct diplomacy without the fear of losing domestic support.

Whether a war between China and Australia is a serious prospect is anyones guess. But what is certain is that when it comes to China, the news media in this country, with The Herald frequently leading the charge, are to varying degrees shifting to a mode of reporting that bears many of the hallmarks of war propaganda.

Judging by the critical some even hilariously sarcastic comments on the Red Alert series on _The Herald_s website, and based on the overwhelming critical responses we have seen in op-eds and social media spaces, it is clear that the Red Alert series has not really achieved its objectives. But we can only assume that the newspaper will keep pushing this particular barrow not in spite of such reactions, but precisely because of them.

The publication of this series has indeed issued a Red Alert about the possibility that our media, to use Hugh Whites apt phrase, is sleepwalking to war, or at the very least sleepwalking into war propaganda. And this is a Red Alert that needs to be taken seriously.