Ross Stitt: 2022 - a tipping point for preferential voting?

July 27, 2022

The rise in support for minor parties and independents may have reached a tipping point that signals trouble ahead for Labor and the Coalition under the federal preferential voting system.

The results of the 2022 federal election point to trouble ahead for both the major parties.

Labor won office. But not well. Against a decaying nine-year old Coalition government led by a deeply unpopular leader, the ALP recorded its lowest ever primary vote. A Labor MP was the first choice of less than a third of Australians. Preference flows saved the day. Just.

The Coalitions election was even worse. It suffered a calamitous drop in its primary vote. Voters deserted it in huge numbers in many of its traditional strongholds.

Some in the Coalition dismissed the result as a protest vote, as if these voters were only temporarily disgruntled and their support can be easily won back. That may be a serious misreading of a long-term trend.

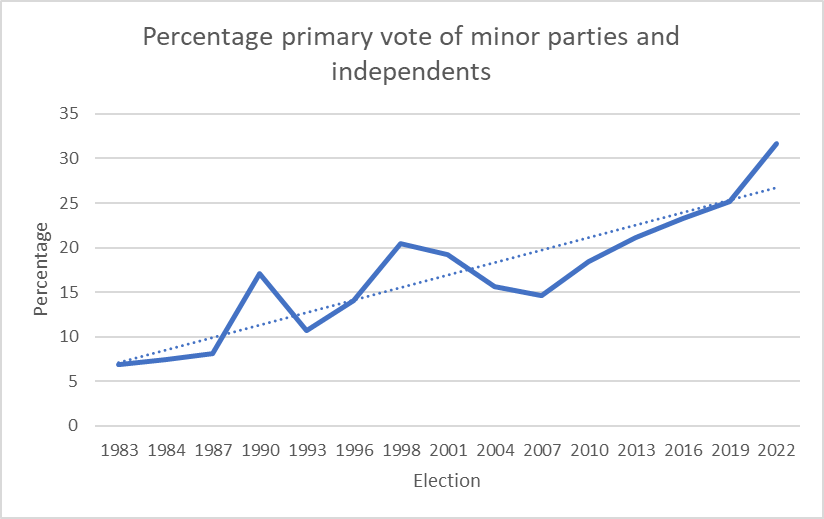

Look at the primary vote won by minor parties and independents over the last 40 years. It paints a disturbing picture for both Labor and the Coalition.

The trend is unmistakable. And its accelerating. Since 2007, support for minor parties and independents has more than doubled to nearly a third of the electorate. At this rate, it will exceed support for Labor at the next election.

For decades, the preferential voting system ensured a form of electoral duopoly for Labor and the Coalition. Minor parties and independents could win 10%, 15%, or even 20% of the primary vote, but it never translated into more than a handful of MPs.

That changed dramatically in May with the Greens, the teals, and other independents winning 16 seats, ten more than in 2019.

Why now? It comes down to critical mass. Where minor party and independent candidates achieved a primary vote above 25% this year, they became competitive under the preferential voting system. In the ten new seats they picked up, they averaged a primary vote of just 32.5% but that was enough to achieve victory on preferences.

Significantly, in nine out ten of those seats, they beat a major party candidate who had a higher primary vote.

The danger for the two major parties is that this success may create momentum for minor parties and independents.

Labor and the Coalition have long argued that a vote for anyone else is a wasted vote because minor parties and independents win few seats, and when they do, they are outside government and exercise no power. 2022 challenges that argument. 16 seats in the House of Representatives is consequential. Labors margin is wafer-thin, and it cannot ignore the large crossbench.

Perhaps more importantly, the success of the new arrivals has elevated the issues they promoted in the election. That will continue given their ongoing voice in the new parliament.

All this is appealing to many voters who have grown increasingly disaffected with both Labor and the Coalition. It might have a compounding effect and encourage even more people to support minor parties and independents in future elections. That in turn could see more seats won by non-major party candidates.

Perhaps the 2022 election signals a tipping point, the beginning of an unwinding of the longstanding electoral advantage enjoyed by Labor and the Coalition.

Many argue that Australians want certainty in their parliament a majority government whether Labor or the Coalition. They dont want hung parliaments and minority governments.

But that is getting harder to achieve. Australian politics has become more fragmented. More multidimensional. There are now fundamental fault lines across multiple issues economic, cultural, and environmental. Its no longer a simple case of left versus right in one dimension.

Nothing better demonstrates the electoral challenges thrown up by multidimensionality than the crumbling of the Liberal Partys much vaunted broad church. Historically, the party crafted election victories by combining two distinct political philosophies liberalism and conservatism.

One example reveals how that combination is becoming increasingly untenable. Support for same-sex marriage is a useful proxy for assessing the degree of social liberalism in Australian electorates. The 20 electorates with the highest yes tally in favour of same-sex marriage in the 2017 postal survey arguably represent the most liberal electorates in the country.

In the 2016 federal election, the Liberal Party held 10 of those 20 seats. In the 2019 election, after the same-sex marriage survey, that dropped to eight seats. In the latest election, it fell to zero as the party lost those seats to teal independents, the ALP, and the Greens.

Thats remarkable. The Liberal Party does not hold any of the 20 most liberal seats in Australia. Its gone from winning half of them to nothing in six years. So much for the broad church.

Labor has its own problems. Traditionally, it has relied on a broad alliance of the blue collar working class and the progressive left. Satisfying the ever more disparate policy demands of those groups is a more and more difficult task.

The old binary model is breaking down. A growing number of voters are not satisfied by the conventional choice between Labor and the Coalition. They are looking to minor parties and independents that advocate policies more consistent with their specific priorities.

The result? Both major parties are suffering base erosion and have become increasingly reliant on preferences to win seats.

This election, Labor benefitted more from preference flows than the Coalition. It won 77 seats with a primary vote of just 32.58%. The Coalition, with a higher primary vote of 35.69%, won only 58 seats.

At a recent National Press Club, the National Secretary of the ALP, Paul Erickson, was asked what primary vote Labor would need next time to retain power. He replied that the minimum primary for holding on and winning again in our own right is probably 32.58%.

If the long-term rise in support for minor parties and independents continues, that could be difficult.

Ross Stitt is a Sydney writer. A former lawyer, he has a PhD from Sydney University in political science.