Slogans masquerading as policies - the Dutton playbook?

August 6, 2024

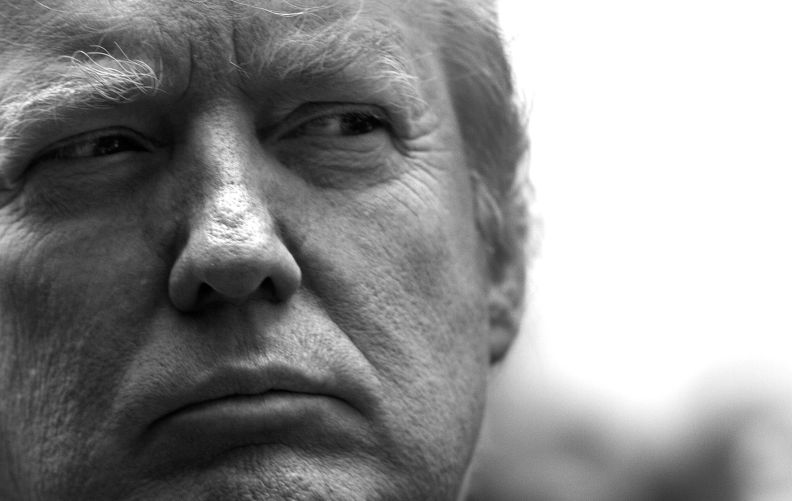

I don’t expect that Donald Trump, presidential candidate, or Trump, elected president, gives a toss whether Anthony Albanese or Peter Dutton is prime minister of Australia after the next Australian election.

That’s assuming that he even knows the names of the major candidates or the parties they represent. Even the name of Scott Morrison has probably dropped off his radar, and, as for Malcolm Trumbull, if he even brings that name to mind again, it will be only with a curse.

Donald Trump has made his first speech on-stage at the Republican National Convention since an attempt on his life to accept the party’s nomination for president, and recounted the assassination first hand.

For Australians, even Australian prime ministers, the outcome of the American election is vitally important, though this fact does not mean that the relationship will change much whether Kamala Harris or Donald Trump is elected. Or, for that matter, whether Albanese or Dutton is in the Lodge. It would affect Australian-American policy or practice, regardless of what the future brings in terms of US relationships with the world, including China, Russia, or Israel.

Most of the US side of the relationship will be in the hands of officials with whom Australians have been dealing for decades.

This is not a mere matter of Australia, under whatever prime minister, going subserviently along with our great and powerful friend. This may be deplorable enough, but it masks the absence of any alternative Australia plan. And - a consequence of this - Australia’s incapacity to make any difference to defence or foreign affairs outcomes outside our own immediate vicinity. It is possible that Albanese, Penny Wong and Richard Marles will be even more slavish than Dutton in their devotion to Trump and his aims, such as they are, if only because of pre-emptive “management” of the certainty that they will be described to Trump as “socialists,” albeit our (tame) socialists.

Albanese also probably understands that any significant movement in Australian defence or foreign affairs policy, other than in our immediate vicinity, would be greeted by effective mutiny by the national security establishment, a good many of whom place loyalty to the western alliance well ahead of their duty to their own country, particularly when it is being led (as they see it) by dolts who do not understand where the “fundamental” national interest lies.

Security relationship beyond mere presidents and prime ministers

As it happens, the national security establishment is not expecting that things will change much, regardless of who wins the presidency. They certainly do not expect surprises affecting our interests on day one in January, whether or not Trump decides to become a dictator for a day.

Abrupt moves, if any, will be focused on domestic policy and ideological flourishes about the shape of government, and probably some eccentric and erratic executive actions. These may disturb those inclined to measure every Trump action as a step on the path to fascism. Or as further demolition of the institutions. But they will not export, or add to existing distrust of Trump’s intentions, foreign or domestic, or of his character and fitness for office.

I doubt there will be any immediate American action on China, and, if anything, some dialling down of the talk of naval confrontation, whether in the Pacific or across the Taiwan Strait. Where there will be change will be a shift of emphasis on to trade disputes, and on transactional arrangements designed to allow both sides to claim victories - perhaps as Australia and China resolved some of their trade conflicts over the past two years. Some of his advisers (and some of Biden’s advisers) have preached the inevitability of military conflict with China, given its growth, and alleged increasing aggression. Some, including their Australian megaphones, effectively argue for American aggression, and the drawing of lines in the sand.

Trump does not believe in any international policeman role, or special duty of intervention in crises far from home. He is scornful of the contribution made by many countries, including the NATO countries, Japan and Israel to their own national security. He may, in general terms, support AUKUS, but he has not mentally committed himself to handing over nuclear-powered submarines if America was short regardless of contracts signed. Luckily, it’s not his problem, because delivery won’t be occurring during his term, even if he unilaterally extends it.

Nothing would concentrate nations on their national interest more than the imminent prospect of war.

Trump is given to boasting of US military invincibility, often in ways that can seem threatening or irresponsible. But he has never indicated any actual enthusiasm for war manifested by the war lobby, including its Australian clones. He has a more considered view of the uncertainties and the completely new social political and military environment if the war became hot. Even assuming a technological superiority by the US, the course, length and cost of conflict is uncertain. So are which nations would be drawn into the conflict. Countries such as Japan, South Korea and Australia will, perhaps for the first time, consider the impact of a hot war on their geographical national interest. Nations some distance away, including Australia, will have to consider very carefully, perhaps for the first time in 75 years, the relationship between fighting a war and its impact, in resource terms, on lines of communication and supply, and blockade.

Many thousands, perhaps millions, would die, in the US as much as in ships on or in the Pacific, among American allies including Australia, and in China itself. Even assuming (as I wouldn’t) that the US ends up ahead on points and body count, the economic and social costs would be fantastic, and the cost of rebuilding enormous. These are not mere economic transactions, stimulating growth, but times of hardship, scarcity and political bitterness. Whether both sides eschew nuclear weapons, and at all stages of the conflict, cannot be predicted or factored into equations.

Only with commitments to Israel has Trump seemed in the least bit sentimental, but if he really is, it is not on his own behalf. On NATO, Ukraine, Russia, Iran and North Korea, he has been entirely pragmatic, without any signs that he cares much about what occurs. He regards most arguments about the impact of US action on “America’s standing or reputation” as actual inducements to throw his hand grenade into the water.

Put simply, he doesn’t care anything about what foreigners think of the US, himself, or their role in international security.

Dutton apes Trump techniques but operates in different system

The Australian parties will be observing the campaigning with as much fascination as ordinary Australians will. They will be absorbing the messaging and the counter-messaging, sometimes with a more knowing, or more detached eye, than Americans too close to the action.

But while there are aspects of Dutton policies that can be called Trumpian, he has only limited capacity to adopt Trump’s campaign techniques.

First are the profound differences in the electoral system, as well as compulsory voting and the electoral college system.

Australia has no presidential figure, nor any requirement to win a majority of the electoral college votes on top of a plurality. Trump’s campaign is based on a strategy of accepting a defeat with the popular vote (as happened in 2016 and 2020) but seeking enough of the smaller midwestern states to deny the Democrats power. There’s no Australian equivalent, though there could be if Dutton were seeking to defeat a referendum proposal.

Australian compulsory voting, independent protection of the voting system and the determination of electorates also prevent the turnout being a significant factor. One side might seek to rally and motivate the age vote, another to mobilise young families with promises about childcare. But in Australia the argument is about issues (or persuading voters to ignore issues) rather than persuasion based on getting voters off their bums and to the polling booths.

What is increasingly similar, particularly from the right of politics in both nations, is the shaping of issues based on impressions, emotions and feelings, rather than “mere facts,” and attempts to galvanise voters with grievances, real or imagined. Framing issues as negative becomes more important than the positive, including, as often as not, the record.

In the US, for example, Trump seems to have persuaded himself as well as a significant part of the electorate that the years of the Trump presidency were years of unparalleled growth, prosperity and economic optimism, followed by years of hardship and retrenchment under Biden.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton reveals the Coalition government’s nuclear plan.

The success of Trump’s imaging is a measure of advertising, the creation of false memories and false facts, and the development of uber-narrative myths about a nation in decline. Talking about making America great again is implicitly describing an America which is now no longer great - economically, militarily, socially and culturally. Add some villains, particularly nasty, criminal and un-American non-white immigrants, and alleged excesses of a metropolitan “woke culture”. Push the fact that white Americans are, comparatively, missing out on employment and economic progress. The latter is, of course, alleged to be a result of illegal immigration and the export of jobs to other nations, aggravated by the way that the white working class feels itself the inevitable victim of anti-discrimination legislation and attempts to provide a social safety net for the poor.

Realising that Trump is a dangerous menace is a reasonable deduction from his record and his character. And from his dog whistles.

Mining anger, alienation and suffering

It is hardly surprising that many Americans, particularly white Americans, feel angry, alienated and neglected, and that Trump articulates their pain. It is noteworthy that JD Vance doesn’t, for all of his enthusiasm for Trump’s cause. Vance, in his American Hillbilly, has blamed the poverty and hopelessness of Appalachian Americans on their own fecklessness, laziness and lack of initiative.

Trump’s championing of blue-collar Americans is good campaigning, even against the facts. Though his references resound with racist dog-whistle, it also appeals to uneducated Black American men, and some Latinos, for its recognition of how the working class has been falling behind. But the success of the campaign is also a reflection on how Biden (and Harris) failed to articulate their policies and their successes, despite campaign funding in the stratosphere. Barack Obama and Bill (though not Hillary) Clinton were still seen to represent the working class.

What ought to be more of a surprise is the extent to which populist nationalism and white resentment has overwhelmed other issues, sometimes to the benefit of the Republican Party itself. That party no longer pretends to be a party of business, focused on creating a society in which the entrepreneur can flourish. Instead, it promotes itself as a working-class party - one necessary because the old party of the working class - the Democrats - has been colonised by elitist left-liberals, pressure groups organised around race and sex, and political correctness. That some leading Democrats such as Hillary Clinton have described some of that working class as deplorables, and undermine what many Americans see as “traditional” (Baptist) values underlines the reality that Trump “owns” most of his constituents, and that the Democrats cannot, in the short term, win them back. It’s a problem aggravated by the outrage factory whenever plain talkers - such as Trump and JD Vance - make critical comments about their rivals.

Trump’s economic program does not offer much to the white working class. That’s a fact obscured by the language of grievance and anger. Trump may be talking up the grievance, but his economic plans involve massive reductions to the size and scale of government. That means reduced services, particularly in health, education and welfare, but also in job-creation and training programs, and in measures which enhance the quality of life, such as a clean environment, clean water and programs designed to protect the public health.

Slogans masquerading as policies, such as about abolishing the department of education with one stroke of the pen, wholesale cuts to the federal public services and ticking off on a billionaire donor wish-list do nothing for the poor, even as they pander to the idea that their impoverishment is a result of mismanaged government policies. Likewise, gestures on abortion, censorship, gender politics and the promotion of Christian culture do not commit Trump to anything much, while leaving to his zealots the task of distracting themselves by trying to criminalise sin.

Dutton is too smart for any aping of the excesses of American Christian fundamentalists, focused on abolishing the 1970s, 80s and 90s. Who want to reverse gay rights and burn transexuals at the stake, criminalise abortion, require crucifixes on assault rifles, and the closure of godless libraries. The ex-cop may be authoritarian at heart, but understands perfectly well that Australia is different, and more tolerant.

Still, he’s up there with government by slogan and vague phrases capable of meaning anything at any particular time, then redefined to mean something else again. Ready to demonise immigrants and, particularly, asylum seekers, unless they happen to be white South African farmers. A libertarian fond of defending freedom of speech for anyone whose cause he favours, an obdurate and unbending champion of tough action, including censorship, for anyone with whom he disagrees. Skilled in the art of avoiding clear statements that can be weighed, counted and measured. Equally skilled in defining and judging, by the most exacting standards, the tricks of the other side. Like Trump, the ordinary guy identifying with the hardworking common man who is only incidentally at the apex end of the richest people in parliament list, with economic attitudes, some borrowed from Gina Rinehart to match.