The 2024-25 NSW Budget - Whither the social housing crisis?

June 20, 2024

The NSW social housing system is in crisis, with more than 58,000 applicants on the waiting list. Another 90,000 households are eligible but have not applied, perhaps because they realise that the prospects of being assisted are slim.

Social housing is secure and affordable rental housing for people on low incomes with unmet housing needs. It comprises homes managed by state and territory governments and by community housing providers (CHPs), including Aboriginal CHPs.

The number of applicants waiting for priority social housing, reserved for those who are homeless or at serious risk of becoming homeless, has been rising sharply in recent times. In areas as diverse as Bankstown, Campbelltown, Bega, Tamworth, and Dubbo, priority lists have more than doubled over just the past three years. This is the result of decades of underinvestment, by both Labor and Coalition Governments.

Since the 1990s the social housing system has largely been expected to be self-funding, with only sporadic announcements of short-term grants and programs. Given that the rents collected from social housing tenants are insufficient to maintain the existing portfolio, the system has been in a state of long-term decline.

Under the previous NSW Labor Government (1995-2011), multiple social homes were sold every week to fund the operations of the system. After coming to power in 2011, the Coalition pursued a different model. Its approach was to redevelop high-value social housing sites, tripling or quadrupling densities. Poorly maintained homes would be replaced with new ones, and 70 per cent of the new stock sold to generate funding with which to maintain and grow the social housing portfolio.

One of the big differences between the two approaches is that the Coalition publicly acknowledged its market-orientation and created a business model to match. While many disagreed with the approach, and it has not led to the boom in social housing stock that was intended, it at least had a clear rationale. In contrast, the previous Labor Government was prepared to sell scarce stock, slowly and quietly reducing the capacity of the system to support those with housing needs.

Leading up to the 2023 election the NSW Labor Opposition indicated that things would be different this time. After winning the election and returning to power, the new Minister for Housing has talked about the need to view social housing as essential infrastructure, and also as a social justice issue.

However, in the 2023 NSW Budget there was no new funding for social housing supply. Instead, the Labor Government began to tinker with its predecessor’s model. In addition to retaining 30 per cent of redevelopment sites as social housing, Labor announced that they would retain an additional 20 per cent as affordable housing. This may be well and good if the affordable housing came with funding, but it did not. Instead, social housing redevelopment projects now use precious funds to support affordable housing, which reduces their financial return, and therefore the resources available to the social housing system.

The 2024 NSW Budget includes funding to build 6,200 additional social homes over the next four years. In delivering his budget speech, the NSW Treasurer claimed that this constitutes the largest investment in social housing since Federation. This boast notwithstanding, three key observations may be made.

First, the increase in homes will barely cover increases in the number of priority housing applicants, should the increase of 1,500 households over the past 12 months continue.

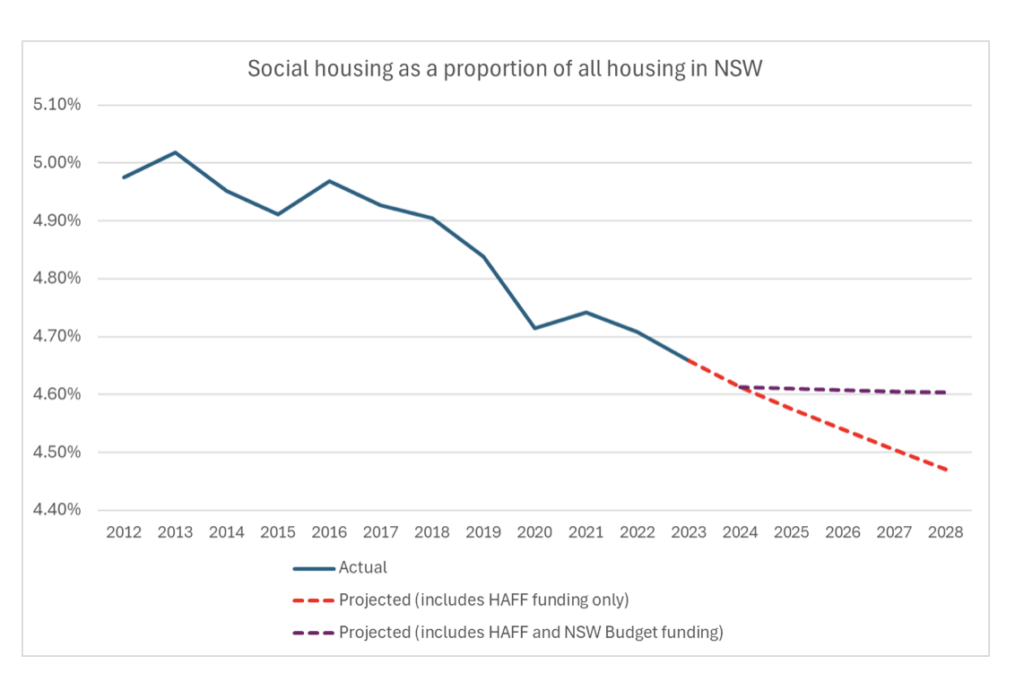

Second, even when the additional stock expected to flow from the Commonwealth Government’s Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) is added to State-funded supply, social housing as a proportion of total housing in NSW is still expected to decrease over the next four years.

Third, while new funding is of course welcome, it can also distract from the fact that need continues to grow, while the supply of social housing relative to population continues to decrease. Rather than addressing the social housing crisis, this budget allows it to grow worse, albeit at a slower pace than would otherwise be the case.

The fictional writer Andrew O’Hagan sums up the situation best:

As soon as something terrible happens… the Left and the Right run to purify themselves, condemning the guilty parties, who are always the parties they expect and wish to be guilty. Meanwhile, the systemic problem remains untouched.

When the number of priority applicants is growing, and the total number of people who need social housing support is similar to the number who already have it, the system is not fit for purpose. If the NSW Government was serious about addressing this crisis, it would acknowledge that the time for reform has long since passed. At this point, only transformational change will do.