The American psychodrama

July 23, 2024

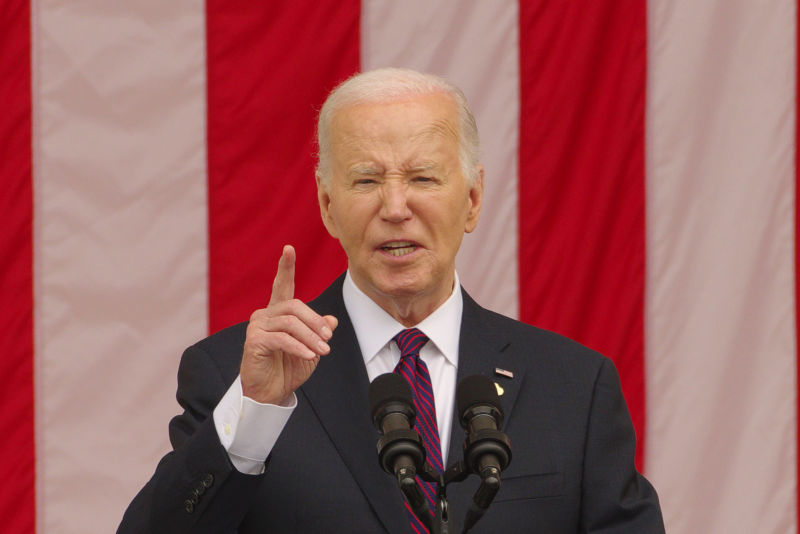

President Joe Biden says only God will prevent him running for re-election. Should Biden drop out of the race, and would Vice President Kamala Harris turn potential defeat into a viable contest between Democrats and Donald Trump?

It is possible that the attempted assassination of Donald Trump has so changed the mood in the United States that no Democrat could defeat him. It is also possible that it gives Joe Biden a new opportunity to withdraw with grace.

Were Biden to seize the moment and say he now needs to concentrate on healing the country and will withdraw from running for a second term in order to do so, he could change the dynamics of the election. At the very least it would pressure Trump to continue speaking of the need for unity, which he has foreshadowed as his theme for his acceptance speech at the Republican Convention later this week.

Sadly it seems neither of these options are likely to happen. A looming presidential contest now pits two men who seem more guided by irrational impulses than by rational considerations or anything beyond their own ego gratification.

That Donald Trump is a narcissist has become a staple of political commentary, but narcissism alone does not explain his extraordinary feat in capturing the Republican Party and forcing all but a handful of his Republican opponents to kowtow to his increasingly extreme and unhinged remarks.

Only a few Republicans seem brave enough to resist Trump, and almost all of them have left office. After a long campaign in which she consistently claimed Trump was unfit for office, Nikki Hayley has now bowed down to the inevitable. This may be explained by a hard-nosed calculus that she needs to do this in order to be a viable presidential nominee in 2028, but surely not every Republican member of Congress fighting for Trump’s approval has ambitions for the Whitte House.

The strength of conspiratorial thinking, evidenced by the number of Republicans who have redefined the 6 January attacks as no more than a tour of the Capital, suggests a psychological willingness to succumb to an authoritarian figure who can mobilise the worst anxieties of millions of Americans.

Traditionally, party discipline has been far less rigid in the United States than Australia; there is no expectation that Congressmen and Senators will always vote with the majority of their party, and many of President Biden’s initiatives were blocked in the Senate by Senators Joe Manchin [West Virginia] and Kyrsten Sinema [Arizona], despite a Democratic majority.

Party lines have steadily sharpened since the 1990s, and there is far less willingness to genuinely negotiate across them. But Trump’s dominance of his party is unparalleled and cannot simply be explained by political calculus.

When Joe Biden was elected he seemed to bring back a sense of order and rationality to decision making in Washington. Unlike Trump he has largely maintained the same senior officials in place and has been surprisingly successful in dealing with a Congress in which the Republicans have narrow control of the House of Representatives.

Biden also positioned himself as a transitional president, one who would restore some sanity after the events of 6 January and allow a new generation of Democrats to take over. His choice of Kamala Harris as vice president was a recognition that this new generation was often led by women and people of colour.

At some point in the last six months something significantly changed in Biden, who now says only God will prevent him from running for re-election. This suggests that beyond any physical and mental deterioration, he has a messianic complex rather like that of Trump, and genuinely believes that he, and he alone, can defeat Trump.

Refusing to confront the evidence of increasingly unfavourable polls and the growing numbers within his own camp calling for him to step down is a sign of a dangerous blindness that threatens to undercut his legacy. Perhaps John Howard could be prevailed upon to call him and remind him of the ignominy that faces a leader who clings to power too long.

The position of the two wives in this psychoanalytic struggle is very revealing. While Melania Trump has been largely invisible, Jill Biden is clearly the major force pushing her husband to remain in the race, rather like Lady Macbeth. The absence of Trump’s favourite daughter, Ivanka, is also striking, though his two sons remain true to the faith

In the short run the assassination attempt has made it less likely that Biden will be forced out, and it has given him one last chance to sound presidential. But consistent polling over the last few months suggests he cannot win [we have yet to see polls reflecting the mood since Sunday, but they will almost certainly further favour Trump].

At this point the best scenario would see him announce that he intends to stand down from the presidency before the end of the year, leaving the succession assured for ice President Kamala Harris, and avoiding a bitter intraparty battle.

Harris now polls better than Biden against Trump, but more significantly she would be in a position to campaign simultaneously as an incumbent and a new face. Sufficient young, Black and Hispanic voters who may not be induced to turn up to vote for either of the two old men could be galvanised to support a Black woman.

Most important, Harris is almost twenty years younger than Trump, and suddenly the optics of the campaign would be reversed. It is hardly surprising that she has struggled to gain traction as vice president; as a loyal deputy she has carefully avoided upstaging her boss. But campaigning as President Harris she would at least convert a certain defeat into a viable contest.

Republished from Australian Institute of International Affairs, Australian Outlook, July 16, 2024