The Assange non-verdict: the threat remains

June 29, 2024

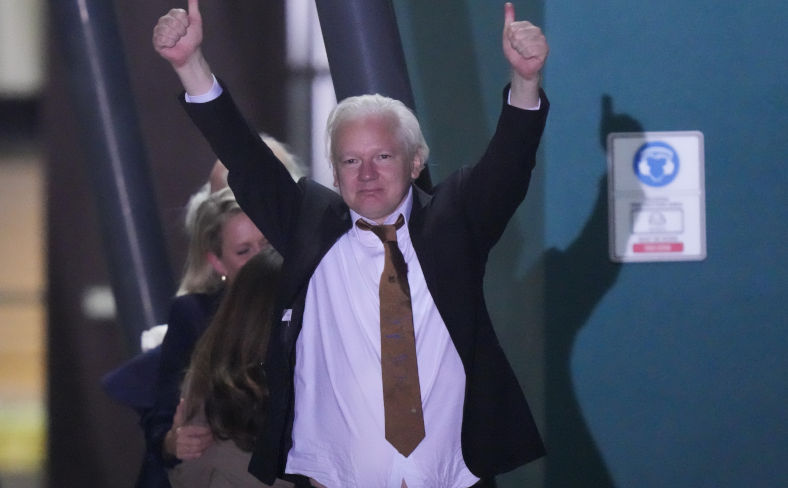

The champers toasting the release of Julian Assange was delightful after many years of struggle against his clearly unjust indictment and years of imprisonment. I am sure we all enjoyed sipping it. After the excitement and sweetness has assuaged however, a certain bitterness still remains, a cold realisation just what his plea bargaining signifies.

Of course, after the hell he has been through no one could blame Assange for accepting the plea bargain. It was a merciful end to a long, merciless campaign waged against him.

The sourness however is in that such a bargain means that what lay at the heart of the charges brought against him still remains, the extra-territoriality of the U.S. ‘justice’ system. That the U.S. understands its laws have global jurisdiction is something still clearly believed by Washington, the only defence against such reach being not to fall either into their hands, or the hands of a state not clearly rejecting such claim.

Of course the idea of a state’s laws having universal jurisdiction has no basis. If I, as an Australian, break Australian law I am tried by an Australian Court. If I as an Australian break Uruguayan law in Uruguay I am brought before an Uruguayan Court. Both Australian and Uruguayan law are limited in their geographical jurisdiction. They claim no more.

I can indeed be tried under Australian law as an Australian for offences committed overseas, most notably trafficking and child exploitation offences, but only as an Australian tried under Australian law. Australian law has no power to indict our Uruguayan friend committing offences in a third country against Australian standards as codified in our law, even if such offences threaten Australian national security. We of course, don’t claim such power.

The U.S. however believes it has such universal jurisdiction and that claim still stands unchallenged, perhaps even technically accepted, in the plea deal being taken. In that there is immense danger.

That danger is present for all, but especially so journalists. Anyone or any journalist who breaches particularly the U.S. Espionage Act (1917), risks being detained, anywhere, as long as that jurisdiction is amenable to doing so. The U.K. shamefully showed itself as being amenable.

Most mainstream journalists having long sold their souls to the ‘proper narrative’ are unlikely to be bothered by such. But for those of the calibre of Daniel Ellsberg and Julian Assange, or to go further back, Wilfred Burchett, the threat looms massively. That of course clearly was the intent of the whole Assange episode.

There are other reasons for a sour after-taste to the champagne.

No doubt Australia, especially our politicians will bask in the glow of Assange’s freedom and the part they played in it. That however is to ignore our own persecution of those, who like Assange, blew the whistle. Not only blew the whistle, but did so regards the most horrific actions.

Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery were put through hell by the Australian ‘justice’ system for their great sin of revealing the perverse immorality of Australian actions against a newly independent East Timor, supposedly our friends, and one of the poorest nations in the world. All done for the benefit of Australian companies at the expense of poor Timorese, using the most underhand of methods, the bugging of the East Timor side. The previous government were rabid in pressing the cases against them, likely because their Coalition predecessors had authorised the bugging. Witness K had no option but to plead guilty, meaning that his ethical actions were found to be criminal under law, even if the sentence was suspended. Law detached from ethics is not a pleasant thought.

As for Collaery, who pleaded not guilty, under the previous government, proceedings, which he compared to a ‘Moscow show trial,’ were set to go ahead, until thankfully the current Attorney-General had the charges dropped.

David McBride however, remains incarcerated, at the beginning of a 5 year 8 month (2 years 3 months non-parole) sentence, his ‘sin’ being the revelation of war crimes allegedly carried out by Australian troops in Afghanistan, claims sustained by the subsequent Brereton Inquiry. Not even Nuremberg and the development of international war crimes law has been able to stand in the way of his incarceration.

We could also speak of Richard Boyle and Daniel Duggan.

The former is another case where Australian governments, as with McBride, Witness K and Collaery, have decided to prosecute a whistleblower uncovering allegedly corrupt actions.

The latter is an instance where Australia, as the U.K. with Assange, display a belief in the universal jurisdiction of U.S. law, given his alleged offences were carried out in South Africa. Already held in maximum security prison for almost two years, Duggan has been found eligible for extradition to the U.S., where he faces 65 years incarceration. Consistency would demand our government, who fought for Assange, should not agree to the extradition.

Yes, rejoice in the release of Julian Assange, but the threat to all of us working to penetrate the lies of the ‘accepted narrative’ is more threatening than ever. Beware the state monster, increasingly without ethics, intoning ‘national security,’ allied with law, sundered from ethics, unleashed and prowling for its next victim, prepared to raise their head above the rampart.