The climate doesnt care who builds batteries

September 1, 2023

Like it or not, the structure of global trade in green technologies and the raw materials required for their manufacture is being decided in an era when geopolitics trump markets, and the WTOs credibility to check the abuse of national security exceptions is near rock bottom.

The upshot, as Mari Pangestu explainsin this weeks lead article, excerpted from the upcoming edition of the_East Asia Forum Quarterly,_is that the green transition is greasing the political skids for a resurrection of inward-looking industrial policy.

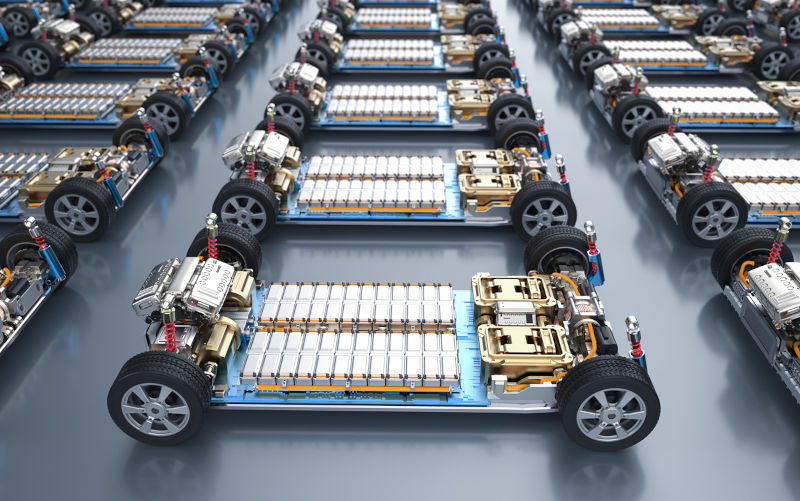

Achieving net zero carbon emissions will require an estimated seven-fold increase in demand for transition-critical minerals between 2021 and 2040, Pangestu highlights. Yet because of Chinas dominance in the processing of these minerals, and in the production of the batteries that need them, developed countries have introduced industrial policies such as reshoring the sourcing of transition-critical minerals and the production of low-carbon technologies.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the electric vehicle (EV) sector. The decarbonisation agenda has dovetailed with a resurgent scepticism of trade and free markets that cuts across leftright divides in the United States. The Inflation Reduction Acts measures to make EVs built with Chinese inputs uncompetitive in the US market, along with efforts by Japan and Europe to force carmakers to diversify their sources of EV inputs away from China, could artificially bifurcate the global automotive industry as the shift away from petrol-powered cars accelerates.

Is the huge advantage China has developed in industries key to the green transition a market failure or security threat that justifies resilience-boosting interventions on the part of other economies?

The idea that China has form in weaponising the critical minerals trade for political ends is prompted by memories of Chinese restrictions on the export of rare earths to Japan in 2010, a move that is often attributed to Chinas anger over the detention of a Chinese national by Japanese authorities during a clash over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

But whether political, as opposed to economic, imperatives drove the 2010 restrictions areless clearuponcloser inspection. China backtracked on the ban not long after, recognising the economic and reputational damage it entailed, and it lost a case brought against it through the WTOs (now semi-defunct) dispute settlement mechanism by Japan, the United States and the European Union. Given that the importance to the Chinese economy of the minerals processing and battery industries has only grown since then, we cant be sure at all that China would cut off its nose to spite its face by restricting the export of minerals or batteries in a crisis at least, not sure enough to pre-empt such a scenario with a brazen attempt to build out Chinese inputs from EV supply chains, as the Biden administration is trying to do.

Ultimately the climate doesnt much care who makes batteries, solar panels, or electric vehicles the interests of the environment, and the vast majority of national governments and consumers, is in green technologies that are abundant and cheap. The problem, as Pangestu writes, is that current industrial policy has the potential to disrupt or raise the cost of access to critical minerals and transition technologies, especially among developing countries.

This point is even more important given the questions about which green technologies will triumph as technical innovation moves more quickly than industries can be restructured witness the uncertainty about the future of the battery industry as new types of battery less dependent on metals like nickel and cobalt grow more competitive. That uncertainty should be at the front of policymakers minds in countries rich in newly-critical minerals, who might be tempted tofollow Indonesias exampleand force investment in downstream industries by banning the export of unprocessed minerals now central to battery production.

Keeping trade open and predictable is as vital to resource-rich countries as it is to resource-poor economies. It is also essential for the diversification of refining and processing capacity to reduce dependence on China, Pangestu says.

Yet this goal lies in want of a platform for its achievement, with the WTO largely out of commission and neither of the major plurilateral free trade agreements in Asia RCEP and the CPTPP offering a forum for the United States, China and the region to come to a workable compromise that sets limits around national security exceptions and keeps markets for key minerals open and competitive, either through newly negotiated instruments or a reaffirmed commitment to relevant WTO rules and processes.

For the membership of RCEP, maintaining the free flow of transition-critical technologies and minerals and facilitating market-friendly opportunities for developing-country members to attract investment into new green industries on market terms should be a top-order priority as member economies flesh outthe economic cooperation agendathat is built into the agreement.

First published in EAST ASIA FORUM August 28, 2023