The cost-of-living crisis: How should the Government respond?

November 22, 2023

Living standards have fallen recently. The Albanese Government has responded with targeted assistance, but the policy options to alleviate the damage for working families are limited, especially in the short run. However, one readily available policy option would be to reshape the Stage 3 tax cuts due to take effect next July.

All the evidence from opinion polls is that the cost of living is the key issue for the majority of voters. According to the director of the Resolve poll, when asked their top priority, voters reply cost of living, cost of living, and cost of living simple.

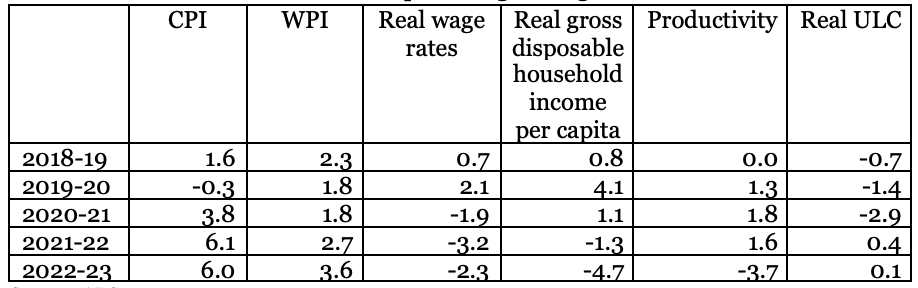

The quick facts are that real wage rates have fallen in each of the last three years (see Table 1). While real household disposable income per capita held up rather better than wage rates, it too fell and by rather more than wage rates in the most recent financial year (Table 1).

Table 1 Key Living Standards Aggregates

Annual percentage change

The other major change affecting the cost of living has been the dramatic increase in interest rates since May last year. This increase in mortgage repayments has affected about one third of households, with an average increase of around $1600 per month. In addition, another third of households are experiencing a significant rise in their rental payments caused by the housing shortage.

Of course, not every household is affected by lower real wages and increased housing costs. For example, the poorest people in the lowest 20-30 per cent of the income distribution are often not affected by the fall in real wages. Equally older people who own their home outright are still very comfortably off, even if the wages of those still working are stagnating.

The ABS publishes data showing the cost of living, including mortgage repayments, for five different types of households: pensioner and beneficiary, employee, age pensioner, other government transfer recipient, and self-funded retiree. For the year ending in the latest September quarter these data report that the cost of living increased by between 5.3 and 6.0 per cent for each of these household groups, except for employees whose cost of living increased by as much as 9.0 per cent.

The obvious reason for this difference is that employees would be much more likely to have a mortgage. In addition, many members of the pensioner groups would have been assisted by the increase in rent assistance provided by the government in the last year.

In short, the people who are most feeling cost-of-living pressures are working families, small business owners and tradies. These people are typically found in the lower to middle income ranges, and they are increasingly concentrated in outer suburban and regional electorates. It may be that their finances are still manageable more so than for people in the three lowest income deciles but these working people feel they are falling behind and often resent what they see as a loss of status.

Traditionally, many of these people were Labor supporters, but in the last three decades they have increasingly switched their support to the Coalition, first as Howards battlers and later as Abbotts tradies. While, on the other hand, Labor has increased its support among the more highly educated, who are not subject to the same financial pressures and whose votes are influenced more by socially progressive issues, such as climate change and the environment, integrity, diversity, and multiculturalism.

It is now pretty obvious that Dutton considers the Coalitions best chance in the next election is to target those working people from the suburbs and regions whose living standards are falling behind, and their associated grievances.

The policy response so far

Since it was elected 18 months ago Labors response to the cost-of-living crisis has included policies to reduce the cost of medicines, doctors visits, child care, and electricity, although for reasons beyond government control, electricity prices are still above the price predicted at the time of the election. The Albanese Government has also supported increases in the wages paid to the lowest paid people on the minimum wage and for low paid people working in aged care.

However, the Governments response to cost-of-living pressures has been limited by:

- What the Government considers to be a severe budget constraint, especially given the unacceptably high rate of inflation,

- A consequent desire to target any assistance to those who are most need, and

- A similar desire to target wage increases to assist the most needy and low-paid workers and again avoid adding to inflation.

What more can be done?

Traditionally the main way that living standards increase over time for most people is via increased wages. However, increases in real wages are largely determined by the rate of productivity growth, and that fell by 3.7 per cent in the last financial year (see Table 1).

Furthermore, although the share of wages in the distribution of national income has fallen over the last thirty years, that is not true of the last couple of years, when unit labour costs rose slightly (see Table 1).

Wages policy therefore needs to assume that nominal wage growth should match the rate of productivity growth plus an increase consistent with the Reserve Banks inflation target for consumer prices. Any faster wage growth risks being inflationary, and the Reserve Bank could be expected to increase interest rates in response.

In short, the scope for government action to improve the rate of real wage growth across-the-board is limited to encouraging faster productivity growth. The Government has plans to improve productivity growth, focusing especially on energy and AI, but these plans will take time to have an impact. Furthermore, productivity growth has slowed substantially in most of the developed economies, including Australia, in the last decade, suggesting that turning around this deceleration in productivity growth will not be easy.

As already noted, the other major driver of the cost of living, apart from negative real wage growth, is the increased cost of housing. This increase in housing costs is being driven by both increased house prices and increased interest rates. Not a lot can be done about interest rates while inflation remains too high, but governments can take action to increase the housing supply. Realistically, this will require an increase in housing density in our major capital cities and State governments are actively pursuing reforms to achieve increased housing density, but it is difficult and is not a short-term solution to lower living costs.

Finally, the third way that governments can act to protect living standards is to offer financial assistance to families, either directly or by way of subsidies for essential services. However, given the continuing budget constraint and the amount of extra assistance already provided, it is difficult to see much more in the way of financial assistance and subsidies that would involve an increase in government outlays.

Any such increased assistance runs the risk of adding to the budget deficit, in which case it might well be matched by the Reserve Bank further increasing interest rates. For the working families who have experienced the biggest increase in their cost of living, this increase in interest rates would add to their problems.

Reduce the budget constraint by reshaping the Stage 3 tax cuts

But there is one way that the Government could change the budget constraint and that is by re-shaping the Stage 3 tax cuts. These tax cuts are heavily biased in favour of the rich whose living standards are not under pressure, with two-thirds of the cost of this third stage assisting the top income quintile of people lodging an income tax return.

A typical full-time worker will get relief of $1000 from the Stage 3 tax cuts but has recently lost a tax off-set worth $1500. In other words, he or she will still be worse off, while a high-income person earning $200,000 would gain an extra $9000 each year.

But the Government could change that if it wished. For example, Matt Grudnoff and Greg Jericho of the Australia Institute have proposed four different alternatives to the Stage 3 tax cuts, which would make taxpayers with incomes up to $120,000 or $130,000 (depending on the option chosen) better off than under Stage 3.

Under Option 4, for example, someone earning around the average wage would be about $1000 per year better off. While the saving of $70 billion in tax revenue over the next decade would be sufficient to fund an increase of $250 per fortnight in the JobSeeker unemployment benefit.

Conclusion

The Governments options to relieve cost of living pressures are limited. There is however, one obvious option which would help the working families who are most feeling these pressures, and that would be to reshape the Stage 3 tax cuts.

The only problem with this is that Albanese has been unwilling to consider this option, even when it was floated by the Treasurer, because he is fearful of the criticism that he would be breaking an election promise.

No doubt Dutton would weigh in with such criticism, but it should not be hard to rebut it, if the change in tax policy is presented as a good response to changing circumstances.

Reshaping the Stage 3 tax cuts as proposed, can readily be argued as providing significant assistance to middle-income working families, on whose behalf Dutton is constantly complaining. What else would Dutton do for these families instead of continuing to complain? He cant have it both ways pretending to be concerned on their behalf while opposing any help that would be of most assistance to them.