The federal budget: what planet does Labour live on?

June 1, 2023

Its astonishing now that the analytical dust has settled on the budget that out of 57 leading Australian economists, most have given it top marks. What planet we may ask do they - and the Labour Government - live on? Not one critically endangered by climate change and a catastrophic decline in biodiversity which collectively pose an unprecedented threat to our (not to mention the worlds) wellbeing and prosperity.

There are those of us who thought that the sheer urgency of these issues might finally be sufficient to implant them as an important part if not the lynchpin of the budgets narrative. Would not Chalmers at some point use his nationally televised speech to highlight these existential threats to the Australian and global economy and at least begin the difficult task of educating the public on the need to thoroughly change our notions of growth and the now essential underpinnings of sustainability? Would not Australias leading economists likewise demand as much of Chalmers? A paltry four out of the 57 economists were moved to criticise the budget for its inadequacy in dealing with climate change. None, as far as I could find, took the government to task on its almost total disregard of biodiversity repair in the budget. Nor did any of the economists care to note that, if budget repair was to be addressed, first we needed to address the fundamental flaws in how budgets are calculated. Which is to say how do we repair the massive destruction of natural capital which has for decades outweighed the gains from (natural capital destroying) economic growth? Being nowhere accounted for in our conventional budgetary system is an inexcusable oversight.

Gentle Jim nevertheless chose another warm, logically fuzzy narrative promising somnolently a stronger foundations for a better future /care and repair/ jobs and growth. With extraordinary skill in his parliamentary speech, biodiversity and climate change get not one single mention. Neither is there any reference to sustainability of our economic activity (other than growth supporting financial sustainability). A dont frighten the horses masterclass.

Still, we might have assumed that in the monumental 64,000 word budget document the real goods are delivered. Well, no. Biodiversity again gets no coverage. Sustainability is mentioned 19 times but in all but 2 instance they again refer to growth supporting financial sustainability.

But does not paydirt come from the 38 references to climate change? No. There is of course the $2 billion for the hydrogen economy but beyond that only a scattering of relatively modest offerings. Much is made of our falling in line with international practice by adopting new accounting methods to clearly indicate what we are spending on climate change. And there is a commitment to indicating future risks to climate change and their likely budgetary implications. Hopes do soar for readers when, finally, a heading A sustainable future comes into view.

Here at last - albeit buried in a tome which very few others than (hopefully) journalists might just read is a chance to highlight the no longer over the horizon threats to Australias future. Here is where the frightening emerging synergy between climate change and biodiversity loss can be laid bare; here is where there can be an admission that carbon neutrality by 2050 is longer an acceptable goal if we are to avoid unacceptably serious damage to our economy; here is where the Government can at least initiate an ongoing conversation with the Australian public in which there is an admission that, while the current budget is about care and (modest fiscal) repair, there is an extraordinarily difficult road of structural transformation ahead; here is where there can be a start to the hugely difficult task of creating the needed national consensus.

Such hopes plummet with the following issue neutered, all but meaningless, motherhood bureaucratese:

Australias natural environment is both an important economic asset and globally unique in its cultural heritage. The Government is ensuring Australia continues to be adaptable to the changing global climate and is committed to protecting our environment for future generations to experience and enjoy.

There follows a jumble of initiatives including $331m going to national parks, safeguarding and supporting agricultural output through a further $1 billion for biosecurity, yet more funds for water security for the Murray Darling basin and more for disaster resilience.

There is no mention of the Governments commitment to preserve 30% of Australias biodiversity by 2030 and no acknowledgement that will take several billion dollars annually to achieve. And no reference is found to the need (as opined by Chalmers not so long ago) to progressively develop a values based budget and which could enshrine sustainability as a central goal.

There is a moment of enlightenment in a reference to the deep, rapid and immediate need to reduce GHG gases in order to limit warming to 1.5 to 2.0 degrees. But that urgency is nowhere else acknowledged or developed. It does not lead to the then necessary admission that current commitments to carbon reduction are thoroughly out of date.

So those of us who were hoping that, rather than just a battlers band aid budget, Labour would cast off its pre-election small target no new policy stance, rightly feel cheated. Much of the returns from a still booming carbon economy have been used to fund the patchwork of albeit admirable care and budget repair initiatives.

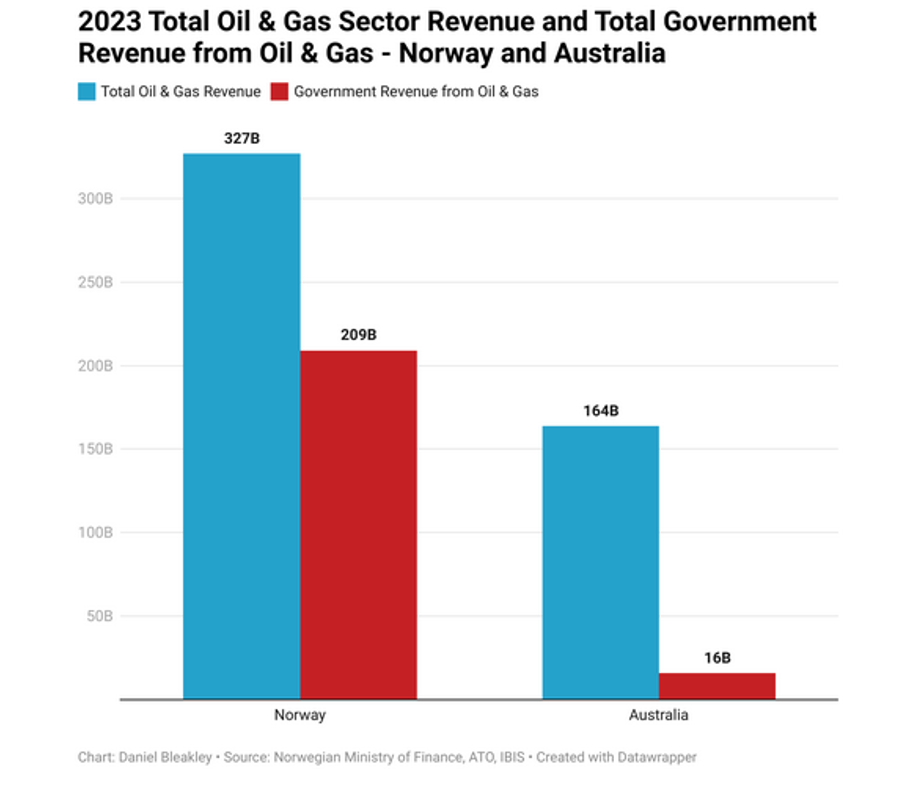

While there is the $2 billion allocated to promote green hydrogen there is no serious spending of political risk capital to further accelerate the transition to carbon neutrality. Witness the bizarrely large subsidies left flowing to the carbon economy. The mining industry still benefits to the tune of $3.5 billion by way of the diesel fuel excise rebate with no thought in the budget it seems of turning it into an engine electrification scheme. Then there is the far larger indirect subsidy from the derisively low taxation of most oil, gas and coal mining companies. Here an extraordinary lack of courage is displayed in the budgets incrementally small increase in the oil (and gas) resource tax which is to produce a mere $2.7 billion over 5 years. The word mere is justly applied. Well documented is the national scandal over our fire sale of our massive gas assets. As Michael West (see graph below) and others have pointed out, two of the worlds largest exporters of gas Norway and Qatar derive vastly more revenues from oil and gas than Australia.

For the Labour Government, applying a just level of royalties and tax is a once in an economic lifetime opportunity to radically increase budget revenue and arguably not one which carries an overly large political risk in the current green political climate. Gas is on its way out and as the IPPC/IEA insist, to have any chance of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees the current volume of gas production should not be increased. The issue is not, therefore, about scaring off unneeded future investors. The returns from investment can far better be derived from securing a rightful maximum return from existing projects and using the resources to accelerate our transition. As it stands, Labour has chosen the worst of both worlds eking out a demonstrably inadequate level of royalties/tax where the only way of increasing the return is from bringing on yet greater output of globally destructive under taxed gas. Rather than frightening the resource horses we are paying a huge price to allow them to sleep.

Gone then from the Labour leadership is the courage of Whitlam, Hawke and Keating for structural reform and gone with it is treasurer Chalmers’ bold new world of values based capitalism. Absent is any pretence of a grand vision in a period of unprecedented economic uncertainty. What planet indeed does the Labour Party inhabit?