The lucky country?

October 23, 2022

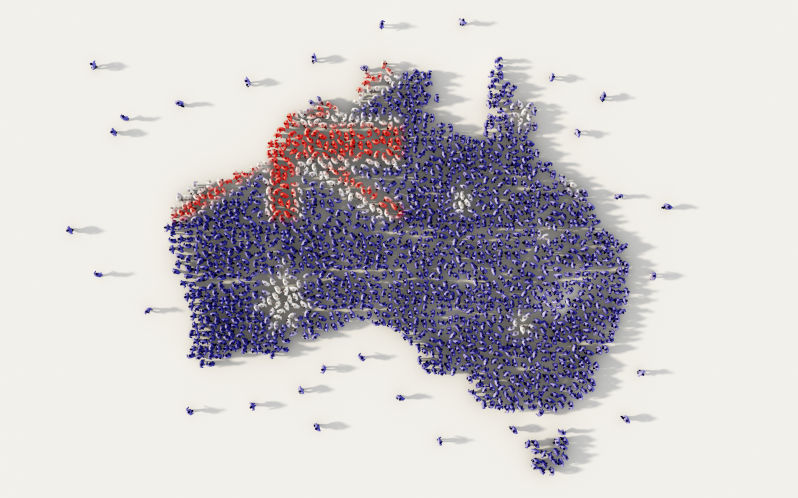

Australia is the spoilt offspring of an ultra-rich empire who gained wealth through exploitative, brutal means.

Just as the United States perpetuates its own destructive national myths, of exceptionalism and manifest destiny, Australia has its own. “The lucky country,” Australians repeat to themselves.

This book-title-turned-national-narrative is just as worthy of examination.

Is it luck? It is like the spoilt child of exploitative, wealthy parents declaring themselves “lucky”. Similarly, Australia is the spoilt offspring of an ultra-rich empire who gained wealth through exploitative, brutal means.

Do others deserve this luck?

COVID reminded Australia that it doesn’t manufacture things anymore. It exports the natural richness of its land. It is wealthy because its parent was wealthy, and others treat it like a wealthy country, i.e. they pay for goods and services at decent prices.

This national claim is accompanied by no genuine sense to help others who aren’t “lucky”. When COVID struck, Australia’s isolated geography as an island continent became an advantage. We shunned one effective vaccine because we thought we deserved the absolute best, with less chance of severe side effects, and pawned what we considered the lesser one on our neighbours.

We contributed little to the rest of the world’s struggles and global vaccine equity efforts, only seeing fit to boast about how ultimately we used our wealth and lucky position to have extra time to vaccinate our population. We hit 2nd, 3rd and 4th vaccine booster shots, in fear of variants that emerged from places with lower vaccine coverage, and didn’t bother to up our contribution to those places.

We used our luck to lecture others about how they should copy us, in spite of the irreplicable geographical factors involved. We also tightened our existing closed borders to places where the situation had worsened.

Australia even abandoned its own citizens during COVID anyway. It was not just the government stranded citizens mentioned the abuse they got from fellow citizens online. To some of us, it was just their bad luck that they were outside the country.

And again, like other Western countries and countries with wealth, Australia acted in a way for COVID that it would never bother to consider for other diseases around the world.

We used our advantages for our own gain, enforcing our self-perception that we are lucky.

Often “we’re lucky” is stated as a sense of entitlement. It was an assertion that I saw, “We’re pretty f**ken lucky in Aus”, made after discussing the present Russia-Ukraine war, that prompted this piece. So apparently we are “lucky” to not have war right here in Australia.

Again, it’s like a rich child observing poverty elsewhere, and then exclaiming how lucky they themselves are. They distance themselves from the horrors that they never deserve, but they think others do.

Not to mention that we also inflict wars on others and commit war crimes, like in Borneo, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. Like other Western democracies, Australia boasts about its system of governance, and uses military force to impose it on others. Then Australians distance itself from the elected leaders of their supposedly superior system whenever they see fit, and do not hold them accountable for crimes that they demonise other leaders for.

And not to mention how disgracefully we treat people seeking refuge and asylum, perpetuating human rights abuses. Apparently we’re lucky and they’re not, and again we don’t see fit to share our luck with them.

And finally, not to mention how exclusively we focus on particular wars and occupations, and ignore other wars, occupations, and humanitarian crises. The Israeli occupation and the system of apartheid in Palestine is a particularly striking case in point.

Is Australia even lucky?

Australians tell themselves that theirs is “a land of opportunity”. That is one source of the “we’re lucky” myth.

But the 2015 and 2020 reports from Educational Opportunity in Australia demonstrate that the Australian Tertiary Admission Ranking is linked with socio-economic status. And in Australia, private schools with Olympic-sized swimming pools and award-winning architecture disproportionately get more government funding than public schools.

On wealth distribution, our unemployment benefits as a proportion to minimum wage are among the lowest in the OECD. And we aren’t committed to removing the Stage 3 tax cuts aimed at those on wealthier wages.

The list goes on. Australia’s bureaucratic systems entrench elitism and remove opportunity for many, rather than provide it.

A country used to attributing every success to luck renders itself incapable of serious reflection on ineffective systems. It robs itself of true independence from its wealthy parent, the United Kingdom, and protector cousin, the United States.

In essence, the myth of the “lucky country” is used to perpetuate our sense of entitlement, both when disaster strikes globally and to shun any responsibility of helping others. Repeating the myth subverts us from investigating whether it is actually true or not, so it is particularly counterproductive.