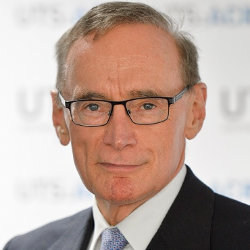

Taking the high ground: let kindness have its day

September 18, 2023

I lost any reservations about The Voice after seeing a movie.

Ive long opposed a charter of rights because it might steer policy-making away from parliament and into courts. If there was someone on the Labor side who might have needed assurance The Voice would not do this, it might have been me. But not after the opening scene of High Ground.

This 2020 movie, directed by Stephen Johnson, is set in Arnhem land in the early 1920s. It was about race relations on the Australian frontier.

It opens with Aboriginals at a waterhole, an oasis of palms and running water. This peace is shattered by fire from repeater rifles. When it stops the only sound is the flight of waterfowl and the buzzing of flies around black corpses. Blood ran in the sand.

That scene was inspired by the Gan Gan police massacre of 1911.

It confirmed the power of visual media in dramatising what the law calls mass atrocity crimes. Think of Steven Spielbergs 1993 Schindlers List. Or Ken Burns documentaries, The West, The Vietnam War and The US and the Holocaust. There is Rachel Perkins documentary The Australia Wars, broadcast on SBS in 2022 and backed by the work of two dozen historians. It detailed the forcible displacement of Aboriginal people to make way for expansion of grazing- a violent displacement.

My response to the terrifying scene that opened High Ground went like this. The survivors of this are saying that all they want is a pipeline to parliament called The Voice? Thats all? Only access? Just give it to them. No argument. No delay.

I have no romantic view of pre-1788 Australia. The story of colonisation is no single narrative. Its jostling counter narratives. Some are happy like the triumph of our British-derived civic culture or our success at merinos and mines. A lot of good things arrived with the First Fleet. I support January 26, believing it can be re-imagined by First Nations as a triumph of Aboriginal resilience; they can rebaptise it Survival Day.

Yet since historian Henry Reynolds first pointed to the massacres, the evidence has slowly, steadily mounted. Professor Lyndall Ryan at Newcastle University, after 10 years of research, estimates 400 massacres of Aborigines, 12 of whites. Dr Pam Smith, an archaeologist at one site in the Kimberley, has interred bones that had been burnt for six days to disguise the crime.

If there were no other reason to vote Yes on October 14 the cruelty of the Aboriginal displacement- like nothing else in our history-would give us one.

Paul Keatings words from his 1992 Redfern speech say it all. it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion.

John Howard and Tony Abbott, the best debaters in the Liberal camp, argue that The Voice will divide us by race, entrenching race in the Constitution. To this there is a simple reply. The racial divide was decreed by official, uniformed Australia with the vote of our colonial and, later, state legislatures. It was Australian state authority that resolved there were two categories of Australians.

One racial category was to have its land removed without treaty or bargain. One category defined by race, could be marched in neck braces to jail or massacre sites. Only Aboriginal people were classed by museums, as late as 1938, as Australian fauna.

As a former Australian foreign affairs minister, I was honoured to meet 14 Caribbean nations in New York and ask them to vote for us in the 2012 ballot for the United Nations Security Council. They approved what I said about the marine environment, climate, banning small arms. But their spokesperson added, unprompted, they liked Australia because of the Apology. The 14 Caribbean states voted for us. Kevin Rudds apology had added lustre to our international reputation.

How is our international reputation going to look if the Australian people are seen to vote down the mildest of constitutional tweaks on behalf of First Nations?

As premier of New South Wales I had the support of all parties when in June 1997 I presented the first apology to the stolen generation delivered by an Australian parliament. When last year we celebrated the 25th anniversary I again met people who had been torn from their mothers and stuck in institutions. One talked of his attempt at escape, walking a stretch of railway line to return to his mother. There is only one racial category of Australians who systematically received that treatment.

If you heard someone on radio talking about being wrested from his mum and stuck in a boys home, then escaping and following a railway line in the hope of finding his way home, you would know that it was an Indigenous Australian.

Now, all these peoples request is a guaranteed Voice to the parliament, with their ideas able to be endorsed or rejected.

Think of the seizing of their land and the savagery that went with it. Its a triumph of the spirit of reconciliation a Voice is all they seek.

Metaphorically, the gunshots still echo. Only one group suffered massacres and now its time to make amends. High Grounds footage is dramatised, but its not fake. Doubters might stream it on SBS on Demand, where they can also find Rachel Perkins The Australian Wars.

Its time to let kindness have its day in public policy.

A version of this article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald September 17, 2023