The Norwegian election was fought and won on climate policy. Are there lessons for Australia?

September 18, 2021

Despite its lowest polling in 20 years, the Norwegian Labour Party will form a coalition government after a campaign largely focussed on the environment and renewable energy. Is this a sign of things to come for our federal election?

Norway is in a unique position. It produces 95 per cent of its electricity from hydro-electrical power and wind farms, 70 per cent of new car sales are electric or hybrid vehicles and it burns no coal. On the other hand, it supplies close to a quarter of the European Union’s gas demand and is Europe’s largest producer of crude oil nearly all of it exported.

This dichotomy is not lost on a populace that except for a hardcore of recalcitrants within the ironically named “Progress Party” largely accepts the climate science and is environmentally aware. The big question in an unusually fierce election campaign was not so much if the country needs to share responsibility for carbon emissions, but how and when.

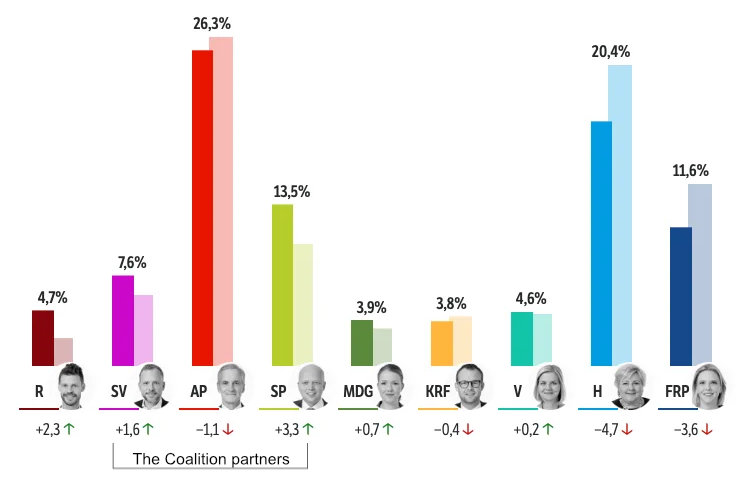

As is typical in most European proper democracies, a plethora of parties contested the election, with seven of them eventually winning seats in Parliament “Stortinget”. The last time any single party (Labour) was able to form a majority government by itself, was in 1961.

The big winner of the election was “Rdt” the Reds, who doubled their votes and got a seat in Parliament for the first time. Their position is to stop all new oil and gas activity and to significantly reduce and end as soon as possible oil and gas production in the North Sea.

The big losers were the two conservative parties who have been in power for the past eight years (mostly supported by two smaller centrist parties). The largest of the two is the Conservative Party (“Hyre”), which agrees with aggressive emission reduction targets but wants to continue to search for new oil and gas fields, including in environmentally fragile areas near the Arctic.

But the really big controversy of the election was not about oil, but about wind power. Over the past decade, Norway has heavily subsidised the building of wind farms, doubling capacity in the last four years to 2,622 megawatts, much of it exported. (Norway’s export of renewable energy is expected to increase eight-fold by 2030.)

In a country of deep fjords, rugged mountains and high plains, most of it freely accessible by a people that generally love the outdoors, the wind farms have become an unacceptable intrusion for many voters; as well as being a danger to an abundant bird population. Even more controversial is the mooted expansion of offshore wind farms.

The Labour Party (“Arbeiderpartiet”) and the new Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Stre will have to navigate his two coalition partners who have very different views on how to protect the environment and handle the climate change challenge.

Norway has already committed to halving emissions by 2030, and to be carbon neutral by 2050. But one of the Labour coalition partners, the Socialist Left, wants much more aggressive targets, while the other, the centrists, traditionally the farmers’ party, supports the current targets.

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/australia-under-funded-despite-our-wealth/

The Socialist Left also wants to stop all new oil and gas exploration, while the other two wants to continue.

Increases in, and the use of, a carbon emission tax is another area where the three parties disagree on how much, how fast and how to implement.

Stre has his work cut out. But he is a former foreign minister and an experienced politician. Norway has long traditions in governing by consensus and compromise and at least he takes on his new role with the knowledge that he has support for changes to Norway’s climate action policies.

The Norwegian election turned on environmental issues, and the Conservative coalition lost power partly because it wasn’t seen to be willing to support stronger climate action.

It is hard to draw direct parallels to Australian politics. Our Labor party is less progressive than its Nordic counterparts, and many of the Coalition’s policies would be alien even to the right wing Progress Party. Norway is firmly grounded in a social democracy painstakingly built from the ruins of World War II. Tinkering too much with the welfare state is political suicide.

We can only hope that Anthony Albanese’s Labor will go the election with well enunciated plans for climate action and seek support of the people on that basis. We can also hope that the Greens find it within themselves to seek compromise and common ground to win influence instead of continued marginalisation. And we can maybe hope for more independents to hold the balance of power.

We could even hope that the Coalition ditches its ingrained support for coal-burning. Or as we say in Norway, “tror du p julenissen?” (Feel free to Google translate, but think pigs with wings.)