The obstacles that now face Chinese FDI in Australia are only partly Australia-made

January 22, 2024

In the increasingly geopolitically charged waters of international trade and investment, Chinese technology enterprises are navigating a particularly turbulent current in Australia. The growing scepticism and regulatory scrutiny they face reflect a techno-geopolitical uncertainty, with Australia caught between its economic interdependence with China and strategic alignment with the United States.

China’s pivot from a major recipient to a significant source of foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly through its new technology firms, marks a major shift in the global economic scene. Chinese companies, once recipients of FDI and technology transfer from the West, especially the United States, are now important investors, bringing with them their capital, technology and global ambitions. Australia, with its rich resources and strategic location, emerged as a key destination for Chinese outward FDI. Yet the warm welcome Chinese investment in Australia has cooled considerably in recent years, a change that mirrors the shifting geopolitical landscape and the effect of US-China technological and political competition on Australia–China relations.

After the unveiling of its ‘ going out‘ policy in 1999, China witnessed an impressive annual growth rate of 68.5 per cent in outward FDI from 2001 to 2016. By 2015, it had become the world’s second-largest capital exporter, trailing only the United States. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan, spanning 2011–2016, fortified this outward trajectory with goals to propel Chinese enterprises up the global value chain and advance the internationalisation of the renminbi. Though still limited in scope, Chinese FDI has evolved beyond market expansion and strategic asset acquisition. It now also aims to establish technological prowess through ‘reverse technology transfer’ in foreign markets.

China’s FDI has also made its mark on Australia. Between 2007 and 2022, Chinese firms channelled US$ 111.5 billion into Australia. Before 2017, Chinese investment was pivotal in Australia–China relations. In 2016 Australia was the top destination for Chinese FDI among developed countries.

Traditionally focused on energy and minerals, China’s investment in Australia gradually expanded into commercial real estate, renewable energy and agribusiness. Chinese investment entities have transitioned largely from state-owned to private enterprises. Post-2017, Chinese FDI in Australia declined sharply, dropping from US$10 billion in 2017 to US$590 million annually by 2021. Chinese FDI in Southeast Asia grew from US$4 billion to US$14 billion between 2010 and 2020, and now dwarfs Chinese FDI in Australia.

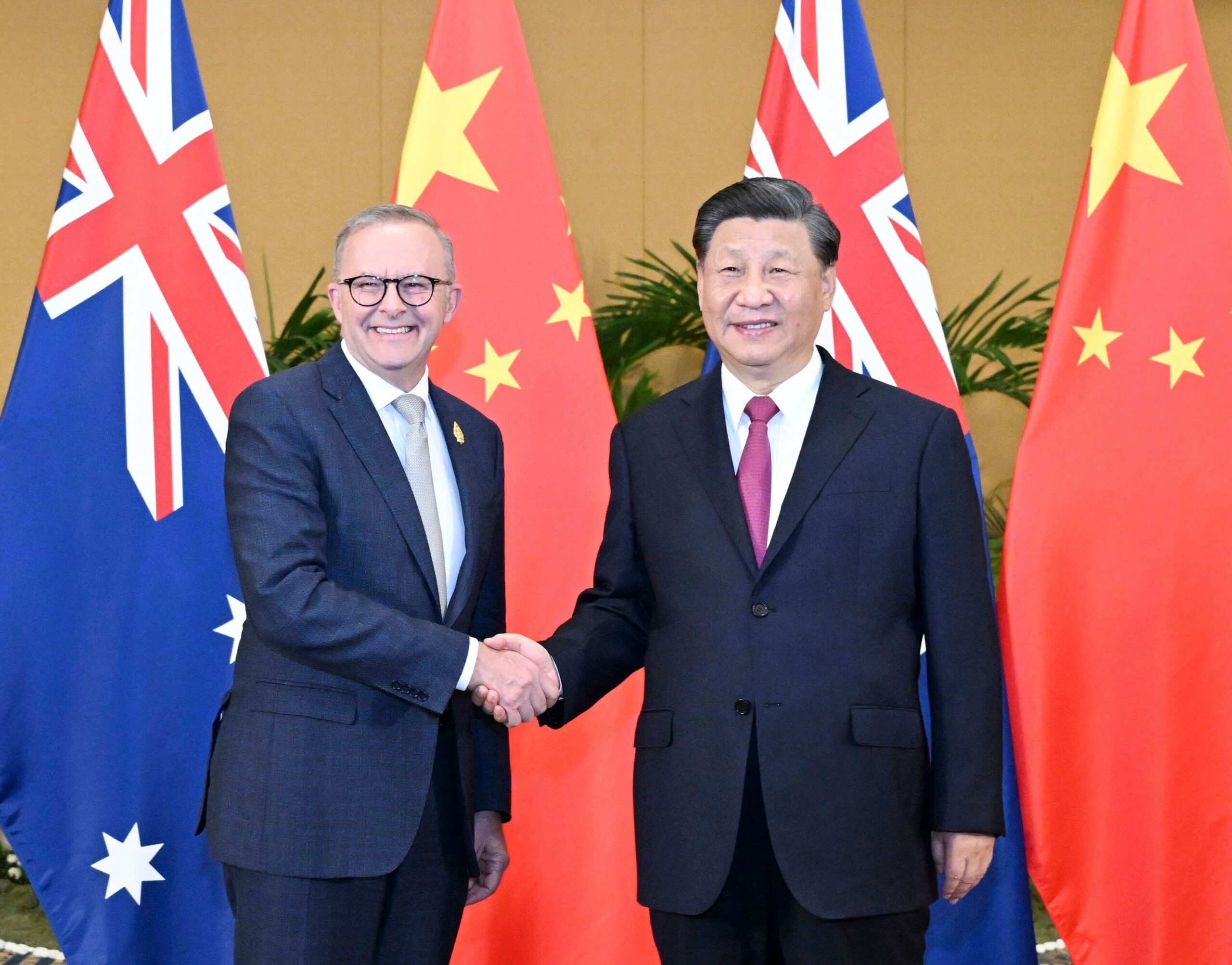

The shift in Australia’s receptivity to Chinese investment reflected changes in Australia’s foreign policy towards China.

The shift in Australia’s foreign policy posture on China was influenced powerfully by its alliance with the United States. In 2016, the United States began implementing protectionist trade and investment measures against China, including by imposing barriers on Chinese acquisition of American technologies and restricting the export of its advanced technologies to China. Australia, without pinpointing specific national security threats by China’s rapid technological advancement, aligned its approach with that of the United States.

Three emblematic cases — Huawei, Tianqi and TikTok — illustrate these shifting dynamics. All three Chinese firms are privately-owned enterprises, and each stands as a testament to China’s technological ascendancy. Huawei is a global innovator in 5G technologies. Tianqi is at the forefront of lithium processing for clean energy. TikTok is a powerhouse in artificial intelligence-driven social media. Their forays into Australia have been met with a mix of enthusiasm and apprehension, highlighting the complex interplay of economics, technology and geopolitics that now confronts Chinese technology companies’ investment in the Australian market.

Huawei’s bid to enter Australia’s 5G network was abruptly blocked by the Australian government, which cited national security risks against its bid to supply 5G infrastructure. The Huawei ban marked the West’s growing unease with China’s technological rise and its potential challenge to its technological primacy. This setback for Huawei underscored a broader caution toward Chinese involvement in vital infrastructure. It also signalled Australia’s tighter policy alignment with the United States and heralded the beginning of the decline in Australia–China relations.

Tianqi’s push into Australia’s clean energy sector highlighted the geopolitical complexities of the industry. As a key lithium processor, a material vital for powering electric vehicles and storing renewable energy, Tianqi’s substantial joint venture faced financial headwinds, market volatility and geopolitical strains over control of clean energy supply chains. Its challenges are indicative of wider concerns over resource nationalism and the securitisation of supply chains in essential minerals, now often seen as matters of national security.

TikTok presented a unique and novel concern. The social media behemoth faced scrutiny in Australia over data privacy concerns and the potential flow of data to China. In the United States and other Western countries, there has been a mounting discomfort about the risks posed by Chinese global digital platforms.

These cases are all related to critical infrastructures that could be used as leverage in broader geopolitical strategies. They are a reminder that the decrease in Chinese FDI in Australia is not just the result of strains in the bilateral relationship but are situated in the geopolitical realignment of international trade and technology.

The challenges facing Chinese tech investments in these areas illustrate the complexities arising from national security, economic and technological considerations. They also point to a wider rise of techno-geopolitical uncertainty affecting technology companies globally. This term refers to disruptions stemming from significant policy shifts in host countries driven by geopolitical considerations.

As the global geopolitical landscape evolves, discussions about technology investments are expected to remain a critical component of international relations. This situation highlights the need for worldwide cooperation in establishing international standards and agreements to regulate the security and compatibility of global technology. In this scenario, whether Australia’s technology sector is perceived as a high or low-risk environment for FDI will be crucial in boosting the nation’s innovation capacity.

Original article published in East Asia Forum on 13 January, 2024