The origin of monarchy is violence: Can Australia choose a new path?

September 24, 2022

The concept of monarchy began as an antidote to human violence.

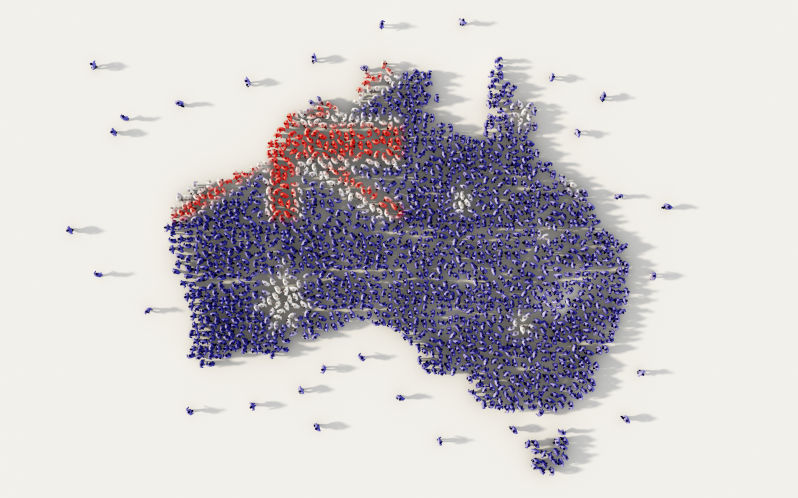

The accession of Charles III is heightening reflection on the probability of Australia becoming a republic. Such a significant social decision benefits from wise discernment of the nature of the systems under discussion. In the matter of monarchy, the French American philosopher and anthropologist, Ren Girard, has a highly intriguing thesis on its origin. He claims that the concept began as an antidote to that endemic and perennial human problem violence.

In summary, his insights include the following. Human beings are by nature imitative. The compulsion to imitate means that humans learn from each other, and occasional brilliant insights ensure the development of ideas and skills. However, humans particularly tend to imitate each others desires. Wanting what someone else has, or wants, appears to be a way of bettering ones situation. So Caveman A sees that Caveman B has a deeper cave and decides that hed also like one. Mrs and Mrs Kardashian realise that the Mayors children attend St Flagrants School, so they enrol their son too.

Trouble comes when people want what cannot be shared. Only one applicant becomes CEO, only one team wins the trophy, and Mary marries John, not Bill. Desire for prestige, an object, or a position introduces rivalry which can become a free-for-all when unchecked by laws and rules.

When Cavemen A and B were house hunting they had no laws. Early societies had to develop ways of dealing with the violence that could spread like a contagion among them because of their shared desires. The rivalry and violence erupting in small communities could wipe them out, because all were pitted against all. Gradually, Girard maintains, a major stroke of human brilliance gained traction. Instead of all against all why not all against one? Venting the communal rage onto a single one had the advantage of ensuring that everyone else survived to enjoy the peace, until the next time.

The choice of the one was important: someone easily subdued, who lacked a family to take revenge, or who wouldnt be missed was necessary. Women were not usually chosen, as they were chattels, and their work was essential. A foreigner, a disabled person, or a child would do.

Of course, the chosen one was the scapegoat. The word is correctly understood as the one on whom the blame wrongly falls. We now know that the scapegoated victim is innocent, but that was not always so. For scapegoating to work properly people had to sincerely believe that the person was guilty of the communal unrest. (A scapegoat is not necessarily innocent of everything, however, and could even be a criminal. A true scapegoat is simply not guilty of the social collapse of which it is accused.)

Sacrificing the scapegoat, killing the victim, was a sacred act that vented the pent-up rage and diffused it. The groups conflict subsided and there was harmony again. Such an outcome was seen as extraordinary. The scapegoat appeared to have two contradictory effects: it was the cause of the social collapse, but also its resolution. How could something responsible for so much violence also quell the violence? Ancient peoples dealt with this amazing yet troubling insight by divinising the scapegoat. Sacred ritual representations and camp-fire narratives of the danger and the salvation gradually produced the great myths, complete with vengeful yet saving gods scapegoats in disguise.

What has all this to do with Queen Elizabeth II or Charles III? Girard theorises that primitive communities knew well that internal violence was recurrent, and so developed the idea of keeping for future use someone whose sacrificial death would bring harmony out of the violent chaos which was sure to come. Future scapegoats were feted as insurance policies. They attracted both opprobrium and veneration, a position through which they forged a certain political power, as they awaited their execution. The resident scapegoat was king.

The sacrificial scapegoat aspects of monarchies disintegrated in their extreme forms with the passage of millennia and the establishment of legal and policing means of containing violence, but their symbolism and stabilising influence remained. Other forms of wielding power have developed, but monarchies still survive in muted forms. A head of state, recognised by all, embodies the desire for the unity and harmony that violence disrupts. The continuity of monarchy brings durability, again a bulwark against division.

These elements were vividly apparent in the funeral rites of Queen Elizabeth II. The immediate acclamation of Charles as King the moment his mother died is a striking display of continuity. Ceremony and symbols from the past represent the stability surrounding the phenomenon of royalty. But the monarch also retains elements of the scapegoat.

The presence of the King and Queen in London during the Blitz exerted enormous symbolic power, presenting the monarchy as willing to die for the people. The sorrow of the British public at the death of Princess Diana was heightened by the absence and silence of the monarch, but the growing anger of the crowds and the tabloids subsided after her delayed appearance. Despite decades of willing relinquishment of power across the globe in the interests of democracy, the occupant of the throne is held to blame for the ignorance, racism, and colonial excesses of the past.

Once the tumult and the shouting dies, the matter of an Australian republic will again be considered, and rightly so. If we choose to be a republic, we must decide whether we will take responsibility for our own actions and our own history, or cling to scapegoats. We must decide from where our stability will spring and what symbols will serve us best.

If these have anything to do with war, then we will be trading a symbol that is transcending its violent roots for something far worse, which will advance Australia nowhere.