The overseas student and immigration nexus: Where to now?

October 11, 2021

As the government faces pressure to bring overseas students back into the country, if it wants a high-quality education sector it should be wary of those only interested in maximising student numbers and short-term profits.

While anti-immigration advocates (incorrectly) describe it as “backdoor” migration, overseas students have been the core of Australias immigration program and policies for more than 20 years.

That will again be the case when international borders re-open with Education Minister Alan Tudge, state governments and the international education industry eager to see a resurgence in overseas student numbers.

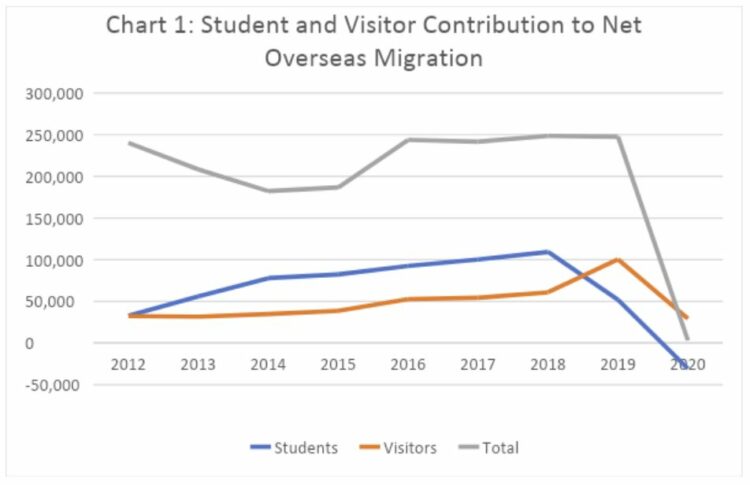

Prior to the onset of COVID-19, overseas students represented more than 40 per cent of net overseas migration, a level that may never again be achieved despite Treasury forecasting long-term net overseas migration of 235,000 per annum (see Chart 1). (The big increase in visitors contributing to net overseas migration would have been driven by a mixture of visitors applying for asylum and family visas (partners and parents) as well as some applying for skilled temporary entry to avoid the long offshore processing times.)

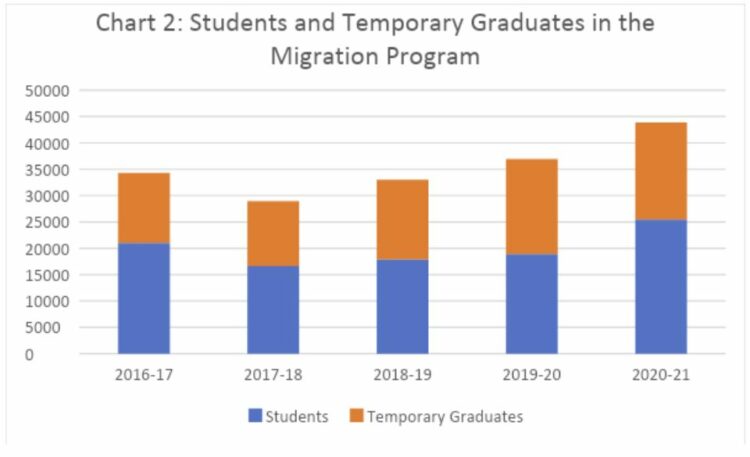

Overseas students and temporary graduates who secured permanent residence represented around 25 per cent of the migration program in 2020-21 (see Chart 2). However, this significantly underestimates the number of students who actually secured permanent migration as it does not include students who used other visa types before they secured permanent residence (eg skilled temporary entry, working holiday, visitors, other temporary employment).

If these other visa types are taken into account, the student contribution to the migration program would be closer to 35 per cent.

But that still leaves a very substantial number of students and temporary graduates who are effectively stuck in immigration limbo constantly trying to maintain their legal status by applying for further onshore student visas or temporary graduate visas whilst looking for a pathway to permanent residence.

Students who had undertaken courses that are attractive to employers and/or are on shortage lists determined by state/territory governments registered nurses were inevitably the top occupation nominated by state/territory governments in 2020-21 will mostly have already been snapped up.

That leaves students and temporary graduates with occupations that are not in demand.

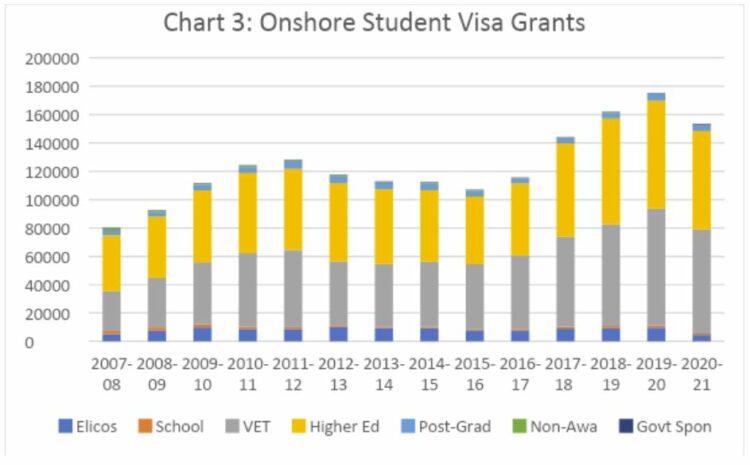

The number of students in immigration limbo is highlighted by the fact onshore student visa grants (see Chart 3) have barely declined during the pandemic, especially once account is taken of the very large bridging visa backlog.

Many of these students will have had no choice but to go to lower cost education providers, particularly in the vocational education and training (VET) sector, while taking advantage of the almost unlimited work rights they now have. Sadly, that will more often than not prolong their time in immigration limbo and low paying jobs.

Where to now?

The public policy risks associated with the overseas student program have remained much the same since the export of education industry started in the mid-1980s. These include:

- Large numbers of students being left in long-term immigration limbo, predominantly because they have undertaken courses that are not in demand from:

- employers or are not regarded by employers as of being an adequate quality; or

- state/territory governments.

- Students with inadequate English language skills or general aptitude to do the course they have enrolled in.

- Students with inadequate finances which means they become heavily reliant on employment well beyond the 40 hours per fortnight traditionally allowed (prior to recent changes allowing almost unlimited work rights). This makes students more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse as well as not having sufficient time to study for their course. It also drives down wages and conditions for the low skilled work that students traditionally do (eg if an employer can get a vulnerable overseas student for less than the minimum wage, why employ an Australian who may insist on their rights?).

- Less reputable education providers becoming involved in a race to the bottom as essentially visa factories offering cheap courses with minimal study requirements to enable students to work in low paid jobs for long hours.

- Education providers becoming dependent on students from a narrow range of source countries and are thereby vulnerable to either a fall in demand from that source country or any tightening of student visa regulations.

The pressure on Tudge and Immigration Minister Alex Hawke to ignore these risks will be intense given the financial losses the international education industry has suffered during the pandemic and its desperation to recover its losses.

The international education industry, parts of which have been shabbily treated by the Commonwealth government, as well as state/territory governments, will be baying for student visa requirements to be “streamlined” in the interests of “cutting red tape” and allowing student numbers to increase rapidly.

Historically, that has meant Home Affairs/Immigration devolving student visa requirements for English language and financial capacity testing to education providers, who in turn devolve these to offshore education agents. While that approach makes sense in some lower risk markets and for some highly reputable education providers, it has been a disaster in high-risk markets and with lower quality providers.

Tudge and Hawke would be wise to treat the streamlining pressure with great caution even if their ideological proclivities are to support cutting “red tape”.

If there is any red tape to be cut in this space, it would be to abolish the so-called “genuine temporary entry” requirement.

This was a nonsense requirement introduced by former immigration minister Chris Evans where immigration officers can refuse a student visa application if they suspect the applicant harbours an interest in permanent migration.

That requirement has made it much more difficult to develop sensible immigration policy which communicates the permanent residence benefits of students undertaking courses that will be in long-term demand in Australia rather than just courses that are cheap to deliver and maximise profits.

It has left the industry unable to properly promote itself as providing a pathway to well-paying jobs and permanent residence in Australia.

How Tudge and Hawke can defend maintaining the “genuine temporary entry” requirement when Tudge himself says many students have gone on to become outstanding citizens of our nation" is a mystery.

But in abolishing the “genuine temporary entry” requirement, Tudge and Hawke must make it clear the government will strongly enforce the range of other protections against the well-known risks to the overseas student program, including strict English language and financial capacity testing.

The government should revert to the 40 hour per fortnight limit on work rights as soon as possible (including stricter enforcement of the requirement). Maintaining the current almost unlimited work rights trashes the reputation of Australias international education industry.

If Tudge and Hawke truly believe in a high-quality international education industry, they would be wise to proceed cautiously and avoid the many spruikers and urgers who are only interested in maximising student numbers and short-term profits.