The Quad: its the US playing catch-up with China, but where does it lead?

February 20, 2022

For the emergence of a sustainable and mutually tolerable Pacific strategic system we should be aiming to make that system inclusive, not split down the middle with Quad.

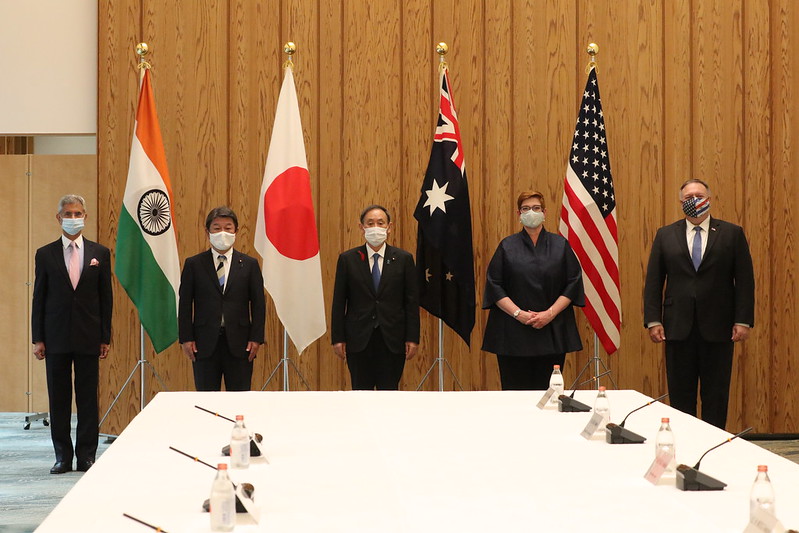

The Quad Foreign Ministers meeting in Melbourne on February 11 sought to portray the developing institution as positive, to be defined not by what we are against but by what we are for, i.e. a free and open Indo-Pacific. But both the areas mentioned in the joint statement issued after the meeting and remarks made outside it, particularly by US Secretary of State Blinken, made clear that for the US in particular it is seen as a mechanism to use, with its allies, to make up for the neglect of the Trump years, and the increased influence and presence of China.

In an interview with The Australians Greg Sheridan Blinken said that To my mind, theres little doubt that Chinas ambition over time is to be the leading military, economic, diplomatic and political power, not just in the region, but in the world. He said that like the US China wants an international order but an illiberal one, while the US wants a liberal order. On his way back to the US Blinken stopped over in Fiji, where he had a virtual meeting with the leaders of Pacific Island countries, and announced that the US would be re-establishing its Embassy in the Solomon Islands, as well as giving greater attention to regional problems like illegal fishing and climate change. A US official was reported (Australian, February 14) as saying that China clearly has ambitions in the Pacific and its playing out regularly and some of what theyre doing is causing real concerns.

In terms of particular issues or areas the meetings joint statement dealt with the importance of ASEAN; plans to supply Quad-supported COVID vaccine to the region in the first half of the year; humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, with Tonga particularly in mind; security in the maritime domain, with a particular mention of the East China Sea, no doubt for Japan; terrorism, with a particular mention of Afghanistan, no doubt for India; cyber; infrastructure; climate change; and opposing coercive economic and trade policies, something for us. It endorsed US plans for exchange and cooperation programs in some of these areas. It also referred to the situations in Myanmar and in North Korea, with particular regard to missiles.

After the meeting the Indian Foreign Minister said in an interview that the Quad nations were drawn together because we have a shared worldview and interests that converge, not because we have any particular immediate pressing anxiety. But he then went on to speak of Indias troubles with China over their border in the Himalayas. And of course while some of the Quads current or proposed activities are commendable in humanitarian or developmental terms its clear that the glue that brought the four together is fear of or opposition to the newly powerful China. The US sees China as a serious threat to its global pre-eminence. There has always been a strand in Japan deeply antagonistic to China. India has its own concerns, exemplified in the Himalayas. And the Australian Government has chosen to demonise China, fears it, talks about fighting a war with it, and would do almost anything to keep the US involved in the Pacific as a protection against China. In that regard it must be very satisfied with the Melbourne meeting. It was noteworthy that Blinken made the journey at all, given what has been going on in regard to Russia and Ukraine. And he spoke to the press about the United States foundational relationship with Australia, and of Australia as our partner of first resort.

So is the Quad a success? As yet its primarily a mechanism, and in its very early days. Some of its proposed fields for non-political activities could be useful and constructive. But they could also be the vehicle for wasteful competition and duplication of effort, if the idea becomes simply to run a Western version of whatever China is doing, for example in regard to the provision of infrastructure (the BRI) and vaccines. The fact is that in some of these areas China is years ahead of the US and its allies, and has runs on the board. As Jonathan Pryke of the Lowy Institute was reported as saying (Australian, of February 14), the US just doesnt have a significant presence in the Pacific. And while there has been some press comment to the effect that The region warms to the Quad (AFR, February 11) no evidence is put forward in support of that. South-East Asia has no alternative to being very conscious of China, and will remain so, however active the Quad becomes. South-East Asian countries dont want a US-China war fought in their part of the world.

Is a US-China clash inevitable? Some American academics like John Mearsheimer say it is, on the basis that the US cannot tolerate a peer competitor, which is very sad, if true. On the other side, many influential Chinese think that the US always tries to thwart Chinas rise, though it may not succeed, since China is rising while the US is declining. (A recent poll showed that China is one of the very few countries where the populations mood is optimistic, as opposed to the West.)

Does Australia have a particular perspective on all this? The present government has certainly whole-heartedly committed us to the US side—see for example Defence Minister Duttons remarks on Taiwan. But until quite recently we had a very different relationship with China, quite developed and many-sided, forward-looking as well as economically very important. The reasons for its deterioration are certainly not all on our side (though we contributed). Chinas activities in the South China Sea, for example (we will not militarise these islands) have made a big impact, as have its economic actions against Australia and Estonia, its threat to Taiwan, and the frequently aggressive tone of its wolf-warrior diplomacy. But we need to remember, when hearing about Chinas misdeeds, that some accounts may be exaggerated or even simply made up. There are well-documented different views of what has been happening in Xinjiang, for example, and while the loss of democracy in Hong Kong is to be deplored there is little doubt that the actions of the demonstrators went beyond what any government would tolerate. China is not the only country that can wage psy-war campaigns, and we need to keep aware of that.

The basic fact about the Quad is that it looks to an Indo-Pacific divided in almost every way between the Chinese sphere and the non-Chinese, or Western, sphere. Is this inevitable? Is it what we want? Do we want to support the construction of our Asia that has as its rationale the exclusion or the minimisation of the role of the largest, most populous and in some ways most advanced Asian country? That is surely not what we want, its not how things have been in the recent past, and its not something that South East Asian countries would want to be part of. In the interests of the emergence of a sustainable and mutually tolerable Pacific strategic system we should be aiming to make that system inclusive, not split down the middle. That would be a better objective for Australia to work towards.