Time to tell the truth at the Australian War Memorial

August 8, 2022

_Imagine an Australia where government agencies operated according to grossly outdated ideas. The Department of Health still accepts the theory of Humours regulating the body; Treasury tries to keep to the Gold Standard; Defence believes in the Domino theory.

_

Ludicrous, isnt it? Of course except that thats exactly what still happens at the Australian War Memorial, our national war museum and the focus of commemoration of Australias war dead.

Decades after the fact of frontier conflict has been accepted, the Memorial stubbornly maintains that the conflict which stained the continent for a century after 1788 is nothing to do with the place where Australia remembers its war dead.

Were used to seeing people reject scientific evidence months ago our streets were full of anti-vaxxers. But its unusual, not to say reprehensible, for a Commonwealth institution to act in defiance of expert opinion.

How come? As ever, a little history is useful.

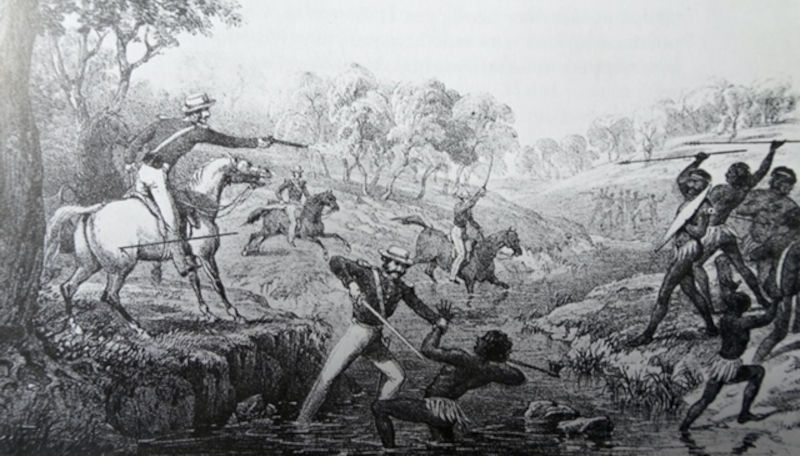

The understanding of frontier conflict has evolved. Contemporaries, black and white, knew what settlement involved. On the Hawkesbury in the 1810s, around Bathurst and in Tasmania in the 1820s, in Queensland from the 1850s, conflict inevitably accompanied British settlement. Just as inevitably, it led to what Charles Rowley called the destruction of Aboriginal society. Drink, disease and the degradation which followed the alienation of their lands completed the process.

Henry Reynolds has shown in his Forgotten Wars that settlers admitted that they were fighting a war for the possession of this continent. That frankness soon mutated into an embarrassed silence. Aborigines had been dispersed, but only for spearing cattle; and look at our prosperous, productive country: didnt that justify some unpleasantness best forgotten?

That great Australian silence, as anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner called it, prevailed until in the 1970s a wave of Australian historians, Noel Loos, Lyndall Ryan and Henry Reynolds leading, began to investigate the records. They found overwhelming evidence of violent conflict. Soon, Indigenous communities spoke of the profound trauma they had suffered. Consensus eventually formed, not without controversy Culture Warriors like Keith Windschuttles nit-picking The Fabrication of Aboriginal History left scars, without changing the essential truth of the story.

In the meantime, Australia had adopted Anzac as what historian Ken Inglis called its secular religion, a response to the traumatic loss of so many in the Great War, justified as a proud foundation story. The temple of that secular faith became the Australian War Memorial, opened in Canberra in November 1941.

The Memorial became a respected place of commemoration and one of Canberras few tourist attractions, but for decades it barely changed, its galleries reassuringly familiar visit-after-visit. In 1975 a new Director, Noel Flanagan, saw it needed to move ahead and deftly steered through the Fraser parliament the Australian War Memorial Act 1980.

Flanagans Act set out an expansive new vision for the Memorial. It remained a centre of commemoration, but now was to preserve and display the artefacts of Australias war history and foster research. And its ambit was not just the world wars, but encompassed war and warlike operations throughout Australian military history. The 1980 Act coincided with and accelerated the interest in military history which saw Patsy Adam Smiths The Anzacs, Bill Gammages The Broken Years, and Peter Weirs film Gallipoli.

The 1980 Act just preceded the re-discovery of frontier conflict. Henry Reynoldss foundation text, The Other Side of the Frontier, appeared in 1981, but the vast body of scholarship which followed established without question that it had occurred.

Further research recognised frontier conflict as a part of Australias military history. John Coatess An Atlas of Australia’s Wars,Jeff Greys A Military History of Australia and John Connors The Australian Frontier Wars, confirmed and documented it. (Nor were these historians red-raggers: Coates was a lieutenant general; Grey and Connor were of the Australian Defence Force Academy not exactly long-haired radicals.)

The Memorial, meanwhile, declined to accept what every serious historian (not to mention Indigenous Australians) understood. The Memorial gradually conceded that frontier conflict occurred, but it now uses its acknowledgment of Indigenous service after 1901 as a smokescreen to conceal its failure to interpret or commemorate frontier conflict. Just this week (in the Canberra Times on 23 July), its director reiterated it was not the Memorials concern. Why not?

The Memorials 1980 Act was passed before research and Indigenous memory established conflict as a fact. It specified that the Memorial dealt with Australian military history, defined as action by military units raised in Australia. The problem you see, the Memorial explains, shrugging its institutional shoulders, was that frontier clashes involved British soldiers, or police, or armed settlers. None were members of military units raised in Australia. What can we do (it asks) besides display an abstract painting alluding to frontier violence?

Two problems. First, members of the Mounted Police, a British military unit raised in Sydney in 1825 did conduct campaigns against Indigenous resistance. So, one of the Memorials responses is and always has been wrong historically.

Second, the Memorials evasive response relies on a ridiculously legalistic definition of war. We now know as we did not in 1980 that conflict accompanied European settlement Those warlike operations made possible the creation of this nation, perhaps Australias most costly conflict. How can an institution intended to commemorate wars and warlike operations evade that reality? Because of a definition in the Act?

Ah, the Act! But what can we do? (More shoulder shrugging.) Heres an idea: change it! Every parliament amends dozens. We need to change the Memorials legislation to make it accord with the reality of Australias history.

On election night, Anthony Albanese promised to act on the Uluru Statement from the Heart. In the spirit of the Uluru Statement we need to ask, how can we attain a fair and truthful relationship with our past and with our fellow Australians unless the national memorial to Australians who died in war acknowledges that truth?

Re published from the Canberra times