TSEEN KHOO. What Anzac Day meant for Asian Australians.

May 18, 2018

This year, just before ANZAC Day, I read a poignant, insightful piece by Nadine Chemali about what new migrants to Australia really thought about Anzac Day.

Chemali’s article brought home to me how starkly many of our new migrants would understand first-hand the sentiment ‘Lest we forget’. She writes: ‘I’m filled with respect for my class of newly arrived migrants, their ability to still reverently honour what Australians call their heroes and survivors, whilst being survivors of war and horror themselves.’

I held Chemali’s optimistic piece in mind as I reflected on Anzac Day more broadly, and what it can mean for Asian Australians.

The day can signal and embrace former war-time foes as contemporary allies. Recent accounts of Turkish Australian Anzac Day connections, for example, mobilise sentiments around mutual commemoration and narratives where the enemy is transformed into ‘one of ours’. Descendants of Turkish soldiers who were at Gallipoli have been allowed to march in Anzac Day parades, and have been considered by some as ‘a very honourable enemy’.

It can also be a day, however, that mobilises the easily ignited racist sentiments around Australians and war, particularly about who ’the enemy’ might still be seen to be. For Asian Australians, there is the overlying, sustained influence of Yellow Peril rhetoric to contend with, as well as the tendency to conglomerate Asians into a cohesive or interchangeable group.

This can be a matter of life and death, as the murder of Vincent Chin (a Chinese American man mistaken as Japanese) demonstrates. My family was once abused by neighbours when we first came to Australia; they yelled at us to ‘go home to Kampuchea’. Being mistaken for a member of other Asian cultural groups in Australia is a common experience.

For Japanese Australians, the connections with Australia’s war-time history continues to be particularly fraught. Whether they are early or more recent migrants to Australia, Japanese Australians have many narratives and expressions of complex identities that are now gaining voice.

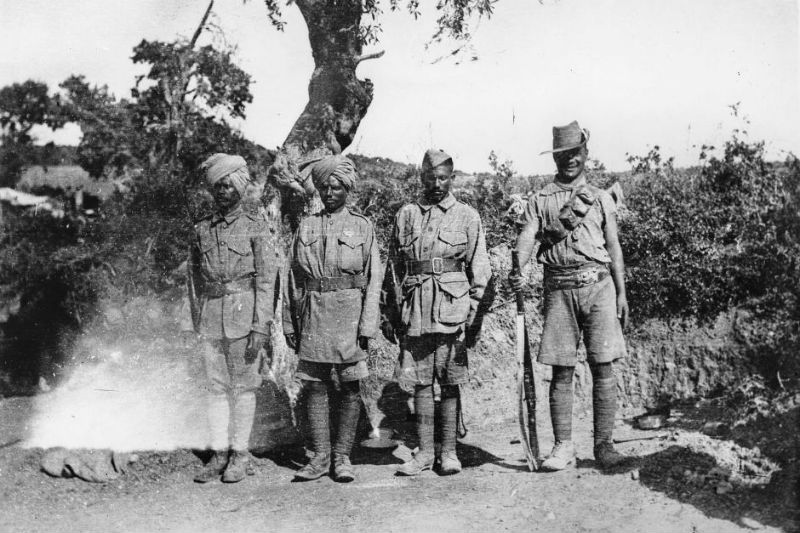

“Recognising our Chinese ANZACs and knowing more about the extent of Indian involvement in Gallipoli goes some way to countering simplistic treatments of that history and how groups might signal ’enemy’ or ‘ally’.”

Mayu Kanamori, a Japanese Australian photographer and writer, writes in ‘Don’t mention the war’ of the complex identity negotiations she works through in Australia. Of her feelings when she returned to Australia in 1996, Kanamori says she felt ‘guilt from the colonialist history’ of her heritage, and conflicted about the sensationalist headlines commonly used by Australian newspapers (for whom she worked) when it came to reporting on war-time commemorations.

In addition, Japanese Australians’ history here includes internment and prisoner-of-war (POW) camps, which have only garnered broader attention relatively recently. Cowra, the regional New South Wales town, has turned its notorious history as a site of a mass prisoner-of-war breakout into major part of its tourism strategy.

This element has shifted from more sensationalist renditions of the history to today’s sophisticated engagement with international partners, universities, and Japanese Australian groups. For example, started in February 2018, the Cowra Voices project creates a textured, geo-located narrative trail that focuses on the town’s initiatives in peace and reconciliation.

The continued focus in research and writing about ANZAC and Australia’s other war-time histories continue to extend and enrich understandings of the events, and increasingly educate us about the roles of diverse Australian groups whose experiences during this period are less well-known. Recognising our Chinese ANZACs and knowing more about the extent of Indian involvement in Gallipoli goes some way to countering simplistic treatments of that history and how groups might signal ’enemy’ or ‘ally’.

Australia’s history of treating Asia and Asians as threats gives rise to repeated bouts of xenophobic politics that inform how Asian Australians may experience national days such as Anzac Day. Sometimes, it’s not just about getting the history more correct, or done ‘better’, and having it known.

This article was first published in Eureka Street on the 7th of May, 2018.

Tseen Khoo is a lecturer at La Trobe University and founder/convenor of the Asian Australian Studies Research Network (AASRN), a network for academics, community researchers, and cultural workers who are interested in the area of Asian Australian Studies. She tweets as @tseenster.