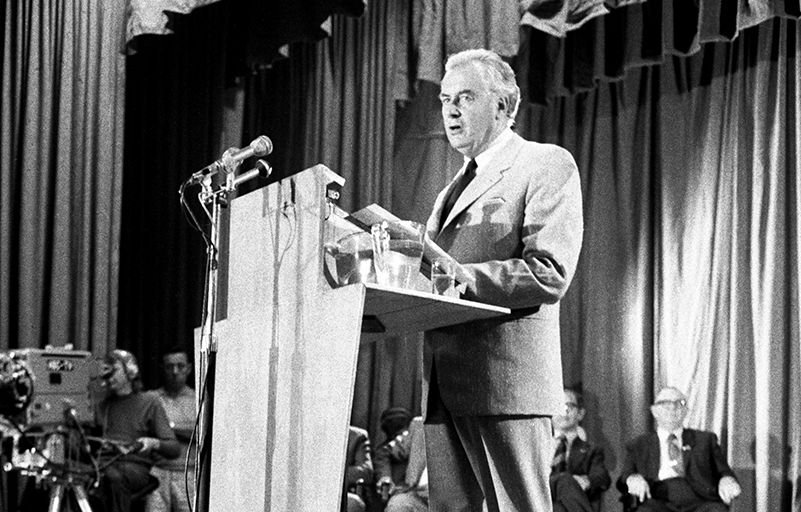

Untruths, the CIA, and Whitlams dismissal

February 13, 2024

A highly regarded commentator on national security, Paul Dibb, has written an astonishing article in the Australian Strategic Policy Institutes The Strategist on January 15 astonishing because it is riddled with major errors.

The worst is his claim, sourced to a CIA official Corley Wonus, that Henry Kissinger had been outraged by Prime Minister Gough Whitlams revelation in 1972 that a satellite ground station at Pine Gap, near Alice Springs was an important CIA spy base. Whitlam revealed no such thing.

Although Kissinger disliked Whitlam intensely, it is not known why Dibb made such a glaring mistake. It was thoroughly established that Whitlam didnt know Pine Cap was run by the CIA until the head of the Defence department, Arthur Tange, reluctantly told him in November 1975, after lying to him in 1972. Tange confirmed that a CIA official Richard Stallings, was the first head of Pine Gap between 1966 and 1969 and later spent part of his time between 1971 and 1974 in South Australia where he performed CIA service at Willunga near Adelaide. It was separately confirmed this service was on the covert action side of the agency.

This did not deter John Blaxland, the author of two volumes of the ASIO Official History, from wrongly claiming Whitlam did not have any official authorisation for his statements about Stallings. Blaxand is now a staff member at the ANU.

Dibb said his working knowledge of Pine Gap came from Wonus who was the CIA Station Chief in Canberra in the late 1970s when I was head of the National Assessments Staff working for the National Intelligence Committee. Strangely, Dibb failed to acknowledge that Wonus was the Canberra CIA station chief in November 1975 one of the most contentious periods in Australian political history. This was when it became public knowledge that Whitlam had finally been told the truth about the CIA running Pine Gap. This meant Wonus mustve known Kissinger was wrong about Whitlam revealing anything about Pine Gap and the CIA in 1972.

Dibb, who remains an Emeritus Professor of Strategic Studies at the ANU, refers to Kissingers appreciation of the crucial role Pine Gap played in reassuring Washington about Soviet compliance with the detailed counting rules of the various strategic arms limitation agreements throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Contrary to Dibbs account, Pine Gap had almost no role in checking on Soviet compliance with the counting rules in the various strategic arms limitation agreements. A former deputy director of the CIA Herbert Scoville, among others, has convincingly explained that photo surveillance satellites in low earth orbit were the crucial verification tools. No such satellites operated from Australia.

Pine Gap could intercept the telemetry signals sent to and from Soviet missile tests to record how a single test missile was performing and if there were any new features. But its relevance to arms control was minimal. It couldnt count relevant weapons. In 2010, the US Defence secretary Robert Gates said telemetry from Russian missiles was not needed to verify compliance with the New Start, Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

However, Pine Gap had a major role in other forms of signals intelligence, including civilian and military communications, as well as radars. It also provided targeting data during wars.

Kissinger sent a message to the US Embassy in Canberra in January 1975 claiming Whitlam knew Pine Gap played a vital role in dtente and arms limitation agreements and wanted him to tell the forthcoming Labor conference this. Once again, Kissinger was peddling a falsehood. As explained above, Australia had almost no role in dtente and arms limitation agreements and Whitlam had not been briefed that it did.

Before the Labor conference, Tange sent Whitlam a note saying, Care would need to be taken not to confirm, or deny, the facilities have a capacity to police arms control and disarmament agreements. Tange subsequently acknowledged in his memoirs that he had not told Whitlam about Pine Gaps supposed monitoring role. Tange would not lightly contradict Kissinger. It would probably take an Australian official he greatly respected, possibly a scientist, for him to take the stance he did.

Dibb correctly said Wonus was the first CIA station chief from the science and technology side of CIA, as distinct from the spooks component. This appointment made him the head American spook in Canberra in the middle of a fraught political crisis. Another spook in the station at that time, told me later during my posting to Washington in the early 1980s that Wonus was not suited to the role and too eager to take action.

Dibb says that in 1978 Wonus told him that Kissinger had demanded the CIA advise him whether Pine Gap could be closed and relocated elsewhere in the world. Wonus said he had firmly told Kissinger that with then foreseeable technology Pine Gap was irreplaceable. He says his was because the signals from the satellite were so tiny the collection facility had to be surrounded by a huge area that was almost completely silent electromagnetically. Wonus said, Pine Gap was one of the very few locations in the world that had such critical characteristics. (Its hard to believe that Wonus, a technical expert, would use the word tiny, rather than weak, to describe a radio signal.) Nevertheless, Dibb said, So, thats how Pine Gap was saved from Kissingers interest in retaliation for the Whitlam governments exposure of one of Americas most important intelligence-collection facilities in the Cold War.

It’s not a convincing story. The more plausible account was given by the Australian defence minister, Allen Fairhall when the US and Australia signed a secret treaty to establish a “joint space research” facility at Pine Gap, a few kilometres southwest of Alice Springs.

Fairhall said the station would occupy 50 acres and be surrounded by a 10 square mile buffer zone to reduce electrical interference. Thats a lot less than Wonus was talking about. There is no reason to believe the US government deliberately underestimated how large the buffer zone would need to be. This figure is broadly in line with the small buffer zone that surrounds other facilities such as the big satellite station at Menwith Hill in a narrow part of England.

The growing city of Alice Springs, with a population of over 26,000, is only 18 km from Pine Gap, continues to expand. Pine Gap is also growing strongly. Its not plausible that the huge buffer zone stressed by Wonus was really needed. In any event, the US has constantly developed larger and more powerful antennae for its satellites to intercept and download signals.

Dibbs claim that Wonus had saved Pine Gap from Kissingers wrath sounds more like a cover story to paint the CIA in a good light at a time when it was suspected of having some part in Whitlams demise. Kissinger, for example, was considering getting rid of the Whitlam government.

A senior CIA official Ted Shackley told me during my posting to Washington that he had Kissingers implicit permission to send an explosive cable from the CIA to ASIO on November 8, 1975. The Agency threatened to cut intelligence ties with Australia if it did not receive a satisfactory explanation of Whitlams comments on CIA activities in Australia which could blow the lid off" Pine Gap by exposing that the CIA ran the Station. I know Whitlam was not the source of that information, but the cable was intended to damage him. Shackley was later promoted to head of the Covert Action Division in the CIA.

A former CIA official I met during my posting to Washington in the early 1980s, Kevin Mulcahy, has a different account of what happened. He told me he became a friend of Corley Wonus when they were working together in the CIAs science and technology division. I knew Mulcahy mainly as a trusted prosecution witness who had helped jail Ed Wilson for selling weapons and explosives to Libya. Wilson had initially worked for the CIA before joining the Naval Intelligences highly secret Task Force 157. The former CIA station chief in Canberra in 1974-75 John Walker told me in Washington that Task Force 157 was operating in Sydney and Melbourne in 1975 but he was not told what it was doing. He later told me Wilson spent many months in Australia in 1975. Shackley maintained an undeclared relationship with Wilson, for which CIA head Stansfield Turner sacked him in 1979.

Mulcahy phoned me Sydney in mid 1981 after I had returned from Washington. He told me that Corley had given him a detailed explanation about what the Agency had done in Australia in 1975. I explained my workload did not allow me to return until later. I shouldve flown Mulcahy to Sydney to hear his account of what Wonus said, but didnt. Later, a colleague Adele Horin approached Wonus in Washington, but he refused to speak to her. I then lost contact with Mulcahy who died on October 26, 1982 outside a rented mountain cottage in rural Virginia.

Two players had a possible motive to want him dead. One was Wilson after Mulcahy had contributed to his going to jail. The other was the CIA after Wonus had allegedly told Mulcahy about what the Agency had done to Whitlam government in 1975.

A final autopsy found that he died from natural causes.

You might also be interested to read the Whitlam Series from Jon Stanford:

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/covert-forces-the-overthrow-of-gough-whitlam-the-series-2/