US military pays $300M to divert Australian communication cable through Diego-Garcia

January 23, 2024

The US military paid $300 million to divert an Australian undersea communication cable to Oman through Diego-Garcia, writes Phil Miller, as facilities at a UK GCHQ surveillance station in the Middle Eastern country have been upgraded ahead of a potentially devastating new war with Iran over Israel.

A base for British spies near Iran has undergone major construction work over the last two years, Declassified has found. Satellite imagery shows a flurry of building work took place at a GCHQ site in Oman, a pro-British autocracy located between Iran and Yemen.

The site is likely to be playing a key role in a region where Britain seeks to counter Yemens Houthi movement and Iranian authorities. Both are opposed to Western support for Israels genocide in Gaza.

Houthi leaders have vowed to blockade Israeli-linked shipping in the Red Sea until Benjamin Netanyahu stops attacking Palestinians. The Royal Navy recently shot down Houthi drones in the Red Sea with UK defence secretary Grant Shapps saying to watch this space for possible strikes in Yemen.

Britain has 1,000 troops stationed across Oman where GCHQ operates three surveillance sites. These include one on the south coast near the city of Salalah, 75 miles from Yemen. Codenamed Clarinet, it was revealed in the Snowden leaks of 2014.

Declassifiedpublished the first photos of Clarinet in 2020, showing its golf ball-style radome, similar in size to some seen at other GCHQ sites. More recent satellite imagery shows extensive construction work within the sites 1.4km perimeter.

Two new buildings have been constructed, with foundations laid for another pair. The largest of the new builds has a footprint the size of six tennis courts and appears to be multi-storied. A GCHQ spokesperson said in response to our findings: Were not able to comment on operational matters.

Undersea cables

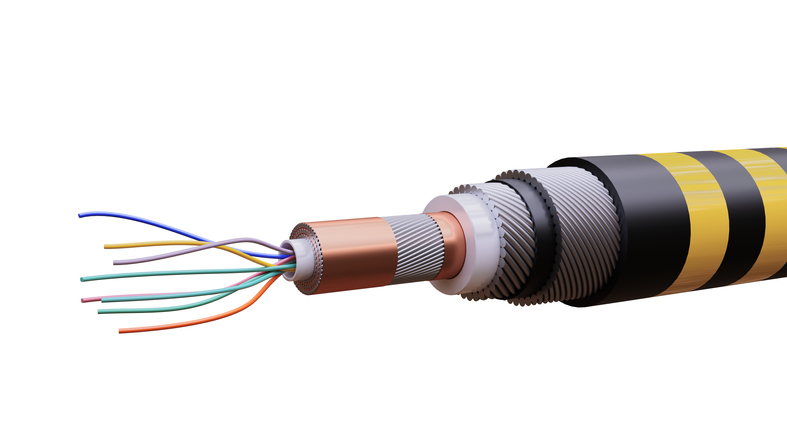

Nautical chartsconfirmClarinet is located at one of the few points in Oman where submarine cables come ashore. These must be marked on charts to prevent ships fouling them with anchors. They carry fibre optic internet cables between continents, allowing GCHQ to hack into online traffic from around the globe.

A new 10,000km communication pipeline, theOman Australia Cable, is being laid between Perth and Salalah. Initially billed as a commercial project led by an Australian firm,Subco, it has since emerged that the cable goes via the US/UK military base on the Indian Ocean atoll of Diego Garcia.

The US military paid$300mfor the cable to be diverted via Diego Garcia, in an operation codenamed Big Wave. Diego Garcia is part of the Chagos Islands, whose indigenous community was evicted by Britain in the 1960s to make way for the US base, in exchange for a discount on nuclear submarines.

The base was a key staging ground for American forces attacking Iraq and Afghanistan, with the Pentagon expected to use it in the event of war with Iran. Installing the fibre optic cable means the base will no longer rely on satellite connections to communicate with the shore.

Perth, a city in western Australia which hosts the other end of the cable, has also become increasingly geostrategic. Last year Britain acquired permission to base some of its nuclear-powered submarines at the port, as part of the controversialAUKUSpact. It will allow the Royal Navy to stage more frequent underwater patrols near China.

GCHQ in Oman

Driving east out of Omans third largest city, the highway from Salalah is flanked with palm trees. Traffic turns right at Maamoura roundabout, funnelling cars between a sprawling royal palace and the vast Razat army base. A mile down the tarmac road is an entrance to a dirt path, guarded by concrete blocks and a police checkpoint.

Most drivers will ignore it and carry on along the coastal carriageway, perhaps stopping at Hawana aqua park or Rotana beach resort. But the select few that turn off here will arrive at an unmarked facility, distinguished by its towering radio masts and giant white golf ball.

Recently labelled on Google Maps as 94 Omantel, it is more than just part of Omans state-owned phone company, which is known to be used ascoverfor spies. According to US intelligence files leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden, a facility matching this description is Clarinet where British spooks are harvesting data from millions of internet users across the Persian Gulf.

Although Snowden shared the leak with the_Guardian_, it did not publish details of GCHQ facilities in Oman. GCHQ went into the media outlets London office to supervise the destruction of the files. The information was only laterrevealedby investigative journalist Duncan Campbell, on an IT news website,The Register.

For Omanis, it confirmed what many already suspected: Britains intelligence services are enmeshed in their countrys security apparatus, a tool that often turns its gaze inwards on them as much as it monitors adversaries.

Repression is the norm in Oman, where all political parties are banned and independent media is muzzled. Oman isranked155th out of 180 countries on the latest world press freedom index published by campaign group Reporters Without Borders.

Oman is effectively Britains best vassal state in the region. Its own intelligence agency was created by British officers, staffed with GCHQ veterans and run by someone on loan from MI6 until 1993. Originally called the Oman Research Department and later renamed the Internal Security Service, it is commanded by the Royal Office.

Thats run by General Sultan bin Mohammed al-Naamani. He has done well for a civil servant, buying a 16mmansionin Surrey from former England football captain John Terry. In 2021,protestsagainst corruption swept the country, secretly organised amid a state-sanctioned march for Palestine.

Solidarity with Palestine

Support for Gaza remains high, making the Sultans alliance with Britain increasingly risky.

Omanis have begun to confront British troops at their aircraft carrier base in the port of Duqm. In avideofilmed at their Renaissance Village canteen, an Omani man told five British soldiers seated at a table: This country [Britain] is f**king pro-Israel, you should get out from here. Piece of s**t. Its time for you to leave from here.

As a British captain tried to walk away, the Omani man criticised Rishi Sunak for sending two naval ships to support Israel after October 7th. Defence minister James Heappeytoldparliament: We are aware of Service personnel being approached in Oman. The safety of our Armed Forces is of upmost importance and the security of our personnel is constantly kept under review.

Mohammed al-Fazari, an exiled Omani journalist and editor of Muwatin, told_Declassified_: If a declaration of war against the Houthi rebels were to occur, undoubtedly the British would employ Oman as a launchpad. Oman has consistently served as a base from which British forceshave been deployed in numerous regional conflicts.

Al-Fazari believes Omanis are unequivocally aligned with the Palestinian cause and their opposition to Britains presence in the country would intensify if it were to be revealed that these military bases were supporting the occupying settler entity of Israel.

Nabhan Alhanashi, an exiled activist who runs the Omani Centre for Human Rights, said he had concerns about the potential utilisation of the [GCHQ] site for activities inconsistent with the interests of ordinary Omanis, especially those with a pro-Palestine stance.

He added: There is a genuine apprehension that the UK, in support of Israels efforts against Hamas, could establish Oman as a partner and ally of Israel, contrary to public declarations.

Omantel, Subco and the US Navy were asked to comment.

First published in DECLASSIFIED UK January 11, 2024