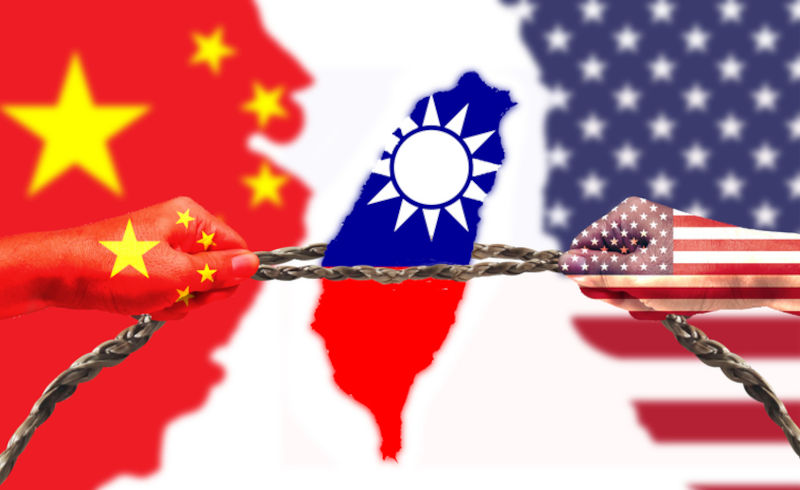

US partly to blame for Taiwan Strait incident

July 7, 2023

A major purpose of US Secretary of State Antony Blinkens visit to China was, in his words, to reestablish communications to reduce misunderstandings and miscommunications to prevent or manage incidents between the two militaries. The 3 June near collision of China and US warships in the Taiwan Strait is a prime example.

But Blinken was unsuccessful in reestablishing the most crucial link military to military communications. Moreover even if better military to military communications are reestablished, dangerous incidents will still occur. This is because they do not stem from misunderstandings and miscommunications but are rooted in deeper differences regarding the international order and strategic interests.

This incident occurred while Chinas Defence Minster Li Shangfu and US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin were attending the Shangri-la security dialogue in Singapore. They may well have known that such an incident was likely. Anyway it provided an opportunity to enunciate their positions.

The two powers are locked in a tit-for tat intensifying struggle for political and military dominance in the region and beyond. In the case of the 3 June incident it was a clash between the US demonstration of its theoretical right under international law versus Chinas right to protect its security. Put another way, the conflict is between the use of a right to gain an advantage over a potential enemy versus a countrys right to defend itself. The incident messaged each sides position and willingness to back it up militarily.

Prior to cutting across its bow the Chinese destroyer radioed the US warship that it should move or there would be a collision. The U.S. alleged that the Chinese warships manoeuvre was illegal, unprofessional, and unsafe. US spokesperson John Kirby said that the close encounter is part and parcel of an increasing level of aggressiveness by Chinas military. In response, Chinas defense Minister Li Shangfu said that we must prevent these attempts that use freedom of navigation to assert hegemony.

To put it in perspective, consider the US reaction if China despite US security concerns- were to repeatedly undertake such activities in the US EEZ to demonstrate their right to do so. While it may not object legally, given the strained relations it surely would be seen as an unfriendly and provocative act. The U.S. would likely monitor them closely, even harass the assets undertaking the activities and plan countermeasures in the event of an attack.

As Kirby also said, Air and maritime intercepts happen all the time. Heck, we do it. The difference Kirby claims is, when we do it, its done professionally, and its done inside international law, and its done in accordance with the rules of the road. So this is a matter of interpretation of professional, the relevant international law and the rules of the road.

The two have long sparred over close-in US maritime and air probes aimed at China. Indeed, this incident came on the heels of what the U.S. called an unsafe and unprofessional intercept of a US intelligence collection plane over the South China Sea. That plane was collecting intelligence on a Chinese aircraft carrier strike group that was undertaking exercises.

The US claims that “The Taiwan Strait is an international waterway, meaning that the Taiwan Strait is an area where high seas freedoms, including freedom of navigation and over flight, are guaranteed under international law.” But the term international waters does not appear in the foundation of the international order in the oceans, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It is an invention of the US Navy to connote to its commanders waters in which they have freedom of navigation.

There are also no legal high seas in the Taiwan Strait. There are territorial seas and contiguous zones. Beyond the territorial sea is an Exclusive Economic Zone in which the coastal state has sovereignty over the resources therein and a responsibility to protect the environment.

The issue for the U.S. is whether or not its warships and warplanes have the right of passage. As a non party to UNCLOS US rights are unclear. Indeed, it depends on what the US warships and warplanes are doing during that passage-and that is secret. Under UNCLOS, they must pay due regard to the rights and duties of the coastal state.

For example, if the warship or warplane is undertaking cyber or electronic exercises, this could be viewed as a threat or use of force - not allowed by the UN Charter - let alone UNCLOS. Indeed, the U.S. views some cyber and electronic attacks this way.

Particularly relevant are active signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection conducted from aircraft and ships, some of which are deliberately provocative, intended to generate responses that can be monitored. Still others may interfere with communication and computer systems. China thinks that some such activities are not consonant with the due regard and peaceful purposes provisions of UNCLOS.

Marine scientific research in the EEZ is subject to the prior consent of the coastal state. If the US warship or warplane is deploying information collection deviceslike drones or sonobuoysthey may be subject to this prior consent regime. Again, since the U.S. is not a party to UNCLOS it has little credibility or legitimately unilaterally interpreting these provisions to its benefit.

The dispute also raises the issue of the status of Taiwan. If Taiwan is part of China as the US One China Policy stipulates, then the entire Strait is under Chinas jurisdiction. The One China policy recognises the PRC as the sole legal government of China, but only acknowledges, and does not endorse, the PRC position that Taiwan is part of China. If the U.S. is implying by its warships passage that Taiwan is not part of China and has separate jurisdiction and regimes governing its claimed portion of the strait, then this challenges Chinas sovereignty claim to Taiwan.

US warships and warplanes have the theoretical right to pass through the Taiwan Strait even if China and Taiwan are reunited– provided they pay due regard to Chinas rights and duties. Otherwise it may be an abuse of right that is prohibited by UNCLOS - in other words using a right for purposes other than that for which it is intended.

But just because it theoretically can, does not mean it should. This is a politicalnot a legal question. The U.S. knows that these probes and passages anger China. Under current circumstances, at the very least they are provocative. The U.S. should have expected a responseprofessional, safe, legal in its eyes or not - especially if it was in Chinas view not paying due regard to its rights.

The U.S. has repeatedly stated and demonstrated the right for its warships to pass through the Strait. This amply protects its legal right to do so. The U.S. needs to consider when enough is enough and whether it wants to risk a dangerous clash to redundantly demonstrate this right.

An edited version appeared in the South China Morning Post on 25 June 2023.