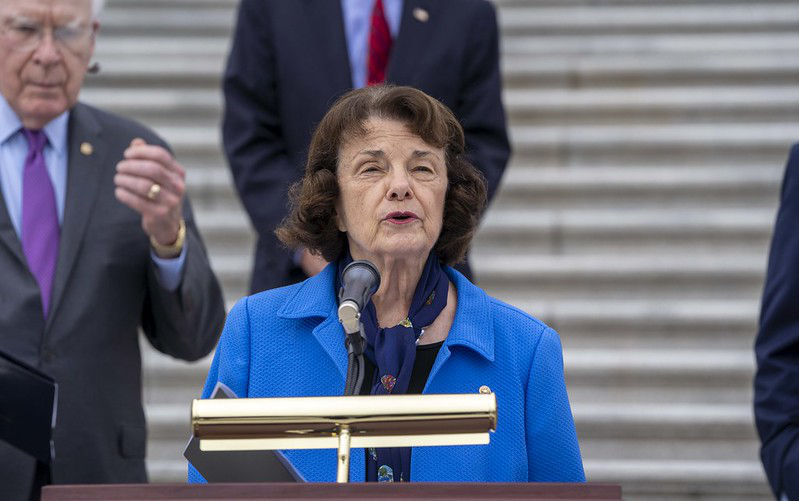

Vale Dianne Feinstein: Persecutor of Assange, servant of the US imperium

October 6, 2023

_She was the longest-serving female senator in US history, a trailblazer for women in politics and a champion for social justice and gun control. So began a piece from the Sydney Morning Herald_s North America correspondent on the passing of Californian Democratic Senator, Dianne Feinstein.

This statement recapitulates the misplaced adulation for one of the most pro-National Security State lawmakers ever elected to Congress. It was Feinstein who, fulminating and raging against the publication by WikiLeaks in 2010 of US State Department cables, openly nailed her colours to the mast of a dangerously novel idea. Those publishing the national security details of the United States, even if based outside the United States and not being US nationals, should still be prosecuted for that fact.

The basis for this ludicrous and now all too threatening idea to the Fourth Estate can be found in her December 2010 article in the Wall Street Journal. In the piece, we see the first express endorsement of the argument that the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, must be prosecuted most vigorously for the crime of espionage. The able and alert at that point must surely have been reaching for the manuals in muddling wonder: Could this Australian national really be guilty for espionage offences, despite publishing material supplied to him, and being a non-US national operating beyond US shores?

From the outset, the senator was adamant that the publication of 250,000 secret State Department cables by WikiLeaks had damaged the US national interest and endangered innocent lives. Feinstein, with no sound evidence or reason, told her readers that the Australian publisher continues to violate the Espionage Act of 1917, a wartime relic that criminalises the possession or transmission by an unauthorised person of information relating to the national defence which information the possessor has reason to believe would be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation.

Feinstein places much truck on the November 27, 2010 advice from US State Department Legal Advisor Harold Hongju Koh. In virtually every respect, its views can be found in the current indictment against Assange, and the legal theory that so enthralled the Trump administration and the Department of Justice.

Tediously, and not acknowledging the fact that the US State Department cables had already been, in their entirety, published by other outlets such as Cryptome, Koh rambles about arguments that make up the current prosecution effort against the publisher: The documents Assange had disclosed would, Place at risk the lives of countless innocent individuals from journalists to human rights activists and bloggers to soldiers to individuals providing information to further peace and security.

Other meretricious views follow with boring banality, all intent on showing the US imperium beyond reproach. The disclosure, Koh argues, risked compromising ongoing military operations, including operations to stop terrorists, traffickers in human beings and illicit arms; and the jeopardising of on-going cooperation between countries partners, allies and common stakeholders to confront the common challenges from terrorism to pandemic diseases to nuclear proliferation that threaten global stability.

Instead of expectorating at such erroneous gabbling (no evidence of these claims has ever been proven), Californias good senator chewed the cud with bovine diligence, steaming away at the claim that Assange broke the law and must be stopped from doing more harm. And as for the First Amendment? [T]he Supreme Court has held that its protections of free speech and freedom of the press are not a green light to abandon the protection of our national interests.

The senator, in views that anticipated the current indictment against the publisher, goes on to undercut the constitutional buttressing offered by the First Amendment by denying Assange the tag of journalist. He is an agitator intent on damaging our government, whose policies he happens to disagree with, regardless of who gets hurt.

Not content with stopping there, Feinstein went further in sharply condemning the publishers attempts to create a social movement that would involve exposing the secrets of the US imperium. For the senator, the secret is always good, the clandestine, necessary.

In July 2012, Feinstein took her call to Australian audiences in a statement sent to the Sydney Morning Herald. I believe Mr Assange has knowingly obtained and disseminated classified information which could cause injury to the United States. In doing so, he had caused serious harm to US national security, and he should be prosecuted accordingly.

While the Obama administration eventually abandoned this approach, Justice Department spokesman Dean Boyd still confirmed at the time that there continues to be an investigation into the WikiLeaks matter. Despite the admission, Australias then Foreign Affairs Minister, Bob Carr, now a devout defender of dropping the case against Assange, scoffed at the notion that Washington wanted the publishers scalp.

Throughout her Congressional tenure, notably as chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Feinstein condemned the leaking culture she had come to see as pervasive. She departed from the original remit of the body she chaired, created in the aftermath of revelations by the Church Committee to provide vigilant legislative oversight over the intelligence activities of the United States to assure that such activities are in conformity with the Constitution and laws of the United States. Instead, Feinstein embarked on a program to plug any inconvenient holes in the national security state, crafting legislation that would address the leaks of classified information, including additional authorities and rules to stop the leaks.

This zealous mission struck certain members of the Washington security set as odd, given the senators own fondness for leaking (and leakers) when it suited her own causes. As Trevor Timm, formerly of the Electronic Frontier Foundation relevantly observed, I dont remember Sen. Feinstein decrying leaks coming from the White House when they led to the Iraq War.

As a case in point, she took issue with a rash of leaks in 2012 disclosing the US role in the Stuxnet cyberattack that crippled Irans nuclear program, the executive decision-making process behind extrajudicial killings by US drones in Pakistan and Yemen and the infiltration of an al-Qaeda Yemeni affiliate by an agent. People, she exclaimed with resignation to CNNs Wolf Blitzer, just talk too much. And this didnt used to be the case, but suddenly, its its like a spreadable disease.

While Feinstein continues to be venerated, an ailing Assange battles a legally spurious document, and the entire machinery behind executing it from his cell in Londons Belmarsh Prison. Any commentary ignoring Feinsteins own contribution to this monstrous state of affairs is not only remiss but unworthy of the column space it takes.