Why history does not disqualify Japan as an ally: a reply to Richard Cullen

February 21, 2023

Richard Cullen’s article, ‘Why Japan is not an acceptable military ally’, published in Pearls and Irritations (5 Jan. 2023) is an unfortunate piece of historical muck-raking.

The core of his argument is that Japan’s record as a brutal imperialist power in the years 1895 to 1945 disqualifies it now, and presumably until further notice, from being a suitable strategic partner for Australia.

His article is flawed in two important respects. First, he exaggerates the exceptionalism of Japan in the awful middle of the 20th century. The three decades from 1930 to 1960 were a horrible time, marked not just by Japanese atrocities but also by the war of annihilation in Eastern Europe, bitter civil wars in China and Spain, Maoist and Stalinist purges, and dirty, destructive wars by colonial powers in Kenya, Vietnam, Algeria, and Indonesia.

Horrible though Japan’s share in this carnage was, it does not stand out from its co-perpetrators and Cullen’s efforts to suggest that it does are based on flawed statistics and on racist stereotypes that derive ultimately from wartime propaganda.

His reference to ‘civilian deaths caused by the Japanese [ranging] from a conservative 10 million up to 30 million’ is a mis-reading of the probably exaggerated official figures that refer to casualties (i.e. deaths and injuries) not deaths.

Rudolph Rummel, whose estimates tend to be on the high side but who is commendably even-handed, has calculated around 10 million Chinese deaths at Japanese hands and nearly as many at the hands of Chinese political forces in the same period. Conservative estimates put the number killed by Japan at around 3-4 million.

Many of the worst stories of Japanese cruelty are fictional or exaggerated, the product of vicious wartime propaganda. In that racist age, Westerners took deep offence at being victims of the kind of racism they themselves felt towards Japanese and other non-Caucasians. The experience of captivity was the worst thing that had happened to them. But that does not mean it was the worst thing ever done.

The death rate from disease and malnutrition among Allied POWs was high, but it was about the same as the death rate among Indian plantation workers in pre-war British Malaya. In 1942, British and British troops in Burma under their own commanders died of disease at a higher rate than POWs on the Thailand-Burma Railway.

Why exaggerate the appalling record of the Japanese? Make no mistake. Japanese soldiers committed a great number of war crimes in the period 1937-1945. The Nanjing and Manila Massacres were amongst the worst single atrocities of the entire war. The medical experiments of Unit 731 were sickening. Millions died as a consequence of Japan’s inability to manage its conquests effectively. But that does not make them like the Nazis.

Nazi Germany carried out the Holocaust, a deliberate and systematic program to murder 6 million Jews. The Nazis murdered two million Soviet prisoners of war. Nothing that Japan did approaches the awfulness of the Nazis. Cullen has unwittingly swallowed the neo-Nazi playbook that seeks to portray the Nazis as relative gentlemen in comparison with the allegedly barbaric Japanese.

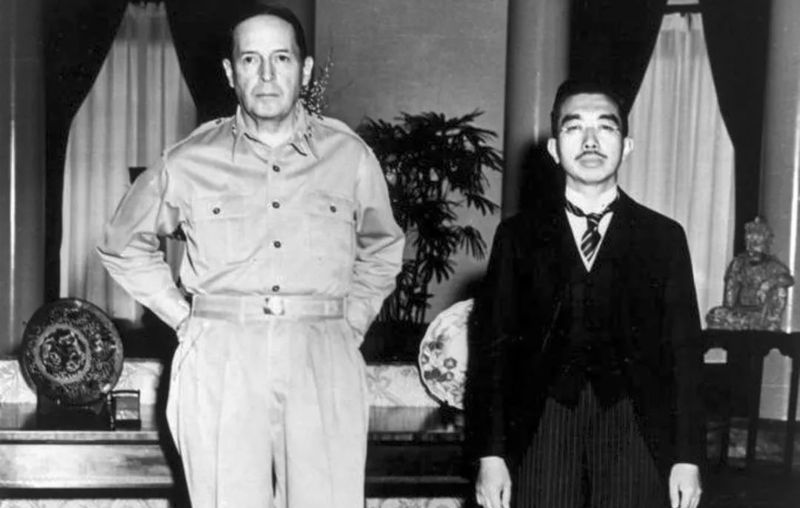

The second flaw in his argument is that it ignores the transformation of Japanese society since 1945. Japan is a flawed democracy, but it ranks well by most international comparisons. The American occupation demilitarised and democratised a Japan that had been governed during the war by a repressive military elite. It was able to do so partly because of the material it had to work with: within Japan was a deep substrate of democratic spirit and practice dating back to the Meiji Restoration. The occupation empowered Japanese democracy, rather than creating it.

There is a minority in Japan that denies the crimes of mid-century, but it is hardly more powerful than the forces denying dark elements in the past of Australia, Britain or the United States. Cullen’s claim that contemporary Japan ‘venerates’ war criminals is simply an ignorant repetition of anti-Japan talking points.

Cullen’s argument would disqualify us from working with Germany or indeed any power that was prominent in the first half of the twentieth century and where there is ambivalence about the past. No cooperation with Britain, then, or the U.S., or France. Perhaps Cullen is simply an advocate for active neutralism, but if so he could have been more even-handed in dishing out the historical blame.

Dealing with a China that asserts its great power status is a real dilemma for Australia. Confronting and antagonising a powerful neighbour who is also a major trading partner is not a sensible approach. A close alliance with Japan may or may not be in our interests. But allowing our policies to be driven by the prejudices of 70 years ago is even worse.