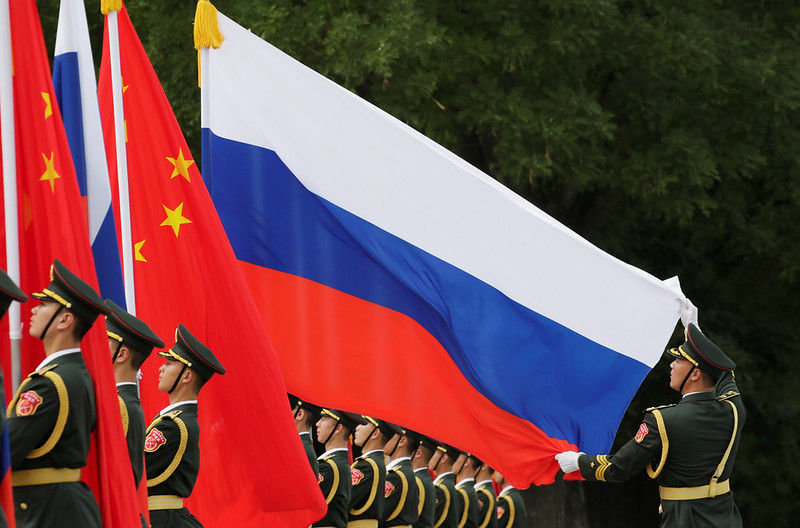

Will Russia join China in the Pacific?

September 13, 2022

For Russia, China is the key was a claim made for the recent Eastern Economic Forum held in Vladivostok annually, and attended by Russias President Putin.

But for China, we could ask, to what is Russia the key?

The Forum was remarkable for the poverty of Chinese participation - a mere sprinkling of academics on the speakers list and attendance only of Chinas number three - though Pandemic preoccupations could be one reason.

It has always been a mystery why the Chinese, never known to be backward in pushing their businessmen and others into distant corners of the globe, have never shown more interest in their enormous neighbour.

Living in Moscow in the sixties there was only one Chinese restaurant in town where we could hope to practice the language and enjoy the food. And even there they did not do much to look after us.

The freeze in relations between the two countries in those days was complete.

Conventional wisdom among conventional China watchers has it that a proud Mao Zedong resented the boorish Nikita Khrushchev claiming to be Communist Bloc leader.

In fact it was the complete reverse. Mao went out of his way to boost Khrushchev in the fifties, not because there was any love between the two but for very hard realpolitik.

China desperately needed Khruschevs promise of support in developing the nuclear weapon Beijing so badly needed to reply to repeated US nuclear threats, first over the Korean War and then Taiwans Offshore Islands.

It was only in July 1959 when the Soviet leader withdrew that promise of nuclear support to China as part of his doomed-to-fail quest for Camp David friendship with the US that a jilted Beijing switched from feigned love to deep hatred towards Moscow.

Disguised as an ideological dispute, that hatred would continue through to the seventies, until a wily Henry Kissinger realised in 1971 he could use it as a lever against Moscow and an excuse for supporting Chinas pingpong opening to the outside world

In the meantime, unfortunately, our simple-minded hawks in Canberra had assumed Beijings 1960s fulminations against Moscow meant China was on a war of liberation crusade which Moscow opposed.

One brutal and mistaken result was Vietnam being dubbed by Canberra as the puppet of a war-mongering China (even though Hanoi was, and remains, much more closely aligned with Moscow, and in 1979 China and Vietnam were at war).

(But dont expect Canberras hawks to say sorry for joining with the US to kill large numbers of the same Vietnamese they now say they need to oppose China.)

But I diverge, even if only for the sake of making the point that Chinas relations with Moscow can be more complex than they appear.

Traditionally they have never been as close as most assume they should be. Beijing looks more to Asia. Moscow not only looks more to Europe; it has sought greatly to be accepted by the West.

That explains Moscows rather bizarre year 2000 request to join NATO (rejected, of course, because NATO cannot exist without an enemy). As Putin put it at the time: Russia is part of European culture. And I cannot imagine my own country in isolation from Europe and what we often call the civilised world. So it is hard for me to visualise NATO as an enemy.

When I was in Moscow in the sixties people would still talk about memories and fears of the Mongol invasions 400 years earlier.

St. Petersburg was long the entry port for European culture. Dubbed Leningrad under the Soviets, the post Soviet regime in Moscow quickly restored its original name. Even Vladivostok, seven flight hours east of Moscow and only two hours from Tokyo and Beijing, remains a completely European style city both in atmosphere and architecture.

The literal meaning of its name: Conquerer of the East.

Russia has produced several Sinologists of repute. But overall academic interest in China is weak, as was shown by the selection of topics for that Eastern Economic Forum: preservation of Amur tigers was a major topic.

Import of Japanese cars able to survive rough Siberian roads remains a major industry. Fortunately, joint development of Sakhalin gas has survived the sanctions.

It is geopolitics, not economics, that is pushing China closer to Russia. US and UK determination to fight the Ukraine war to the last Russian soldier gives a heavily sanctioned Russia little choice but to turn increasingly to the Chinese economy for support. And we may see closer political ties in the future.

But for the moment we may have to rely on those Amur tigers.